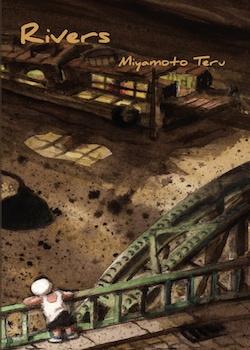

Rivers

By Miyamoto Teru

Kurodahan Press

1 Nov. 2014, 266 pages

ISBN-10: 4902075598

Translated by Ralph McCarthy and Roger Thomas

Review by Chris Corker

Miyamoto Teru has enjoyed huge popularity in Japan, while to readers in the West he remains a relative unknown. Perhaps that is because his fiction, essentially autobiographical, portrays a Japan that does not sit well with the modern, romanticised version of a country recovering immediately after the war, quickly becoming a world powerhouse decorated with neon. The Japan here is much less glamorous. These three stories – spanning decades but always set in Osaka, each by the side of a river – show the daily struggles of a proletariat population, suffering not only from the squalor of poverty but also suffering psychologically with the legacy of defeat. Running through each story is a desperate desire from the older generation to pass on something more to their younger counterparts, to try and offer promise in an environment that drains it away.

‘A newborn had been found floating in the river, trailing a long umbilical cord […]’

Rivers and water are often used by an author as metaphors for purity and cleansing. One thing apparent from very early on in ‘Muddy River’ – set in 1955, a decade after the war – is that while the river may be the lifeblood of the town, it is a stagnant and fetid flow, associated often with death and dissolution. This twisted symbolism is apt for Rivers as a whole, at once nostalgically reminiscent and traumatic. ‘Muddy River’ sets the tone with a particularly striking image, as an already disfigured veteran is crushed under the wheels of his cart as he struggles to push it up a hill. The returning soldiers had escaped the war, but their struggles are far from over. Another is mentioned: ‘He was a farmer from Wakayama, had two kids. Bullets were flying around us like swarms of bees, and he walks away without so much as a scratch. Then, three months after he was sent home, he fell into a ditch and died.’

Shortly after he sees the death of the veteran, a young boy named Nobuo notices a new riverboat in the town. He has no idea as he makes friends with the boy from the boat – Kitchan – that Kitchan’s mother is a prostitute, and that they move from place to place on the river, staying as long as they can before they are forcefully moved on by the authorities. Nobuo, Kitchan, and Kitchan’s sister, Ginko, develop a friendship that at all times feel fleeting, made more pitiful as Nobuo begins to have deeper feelings for Ginko. Later, after a moral disagreement between Nobuo and Kitchan, he stops talking to them. Just like the soldiers back from the war, Nobuo – the younger generation – cannot fully accept the tainted family, forced to extremes just to get by. By the time he finds forgiveness, it is too late.

‘River of Fireflies’, the strongest and most poetic of the three stories and winner of the Dazai Osamu Prize, is a bittersweet coming-of-age tale set amongst tragedy. Taking place during a particularly harsh winter in 1962, ‘Fireflies’ opens with an unhappy family scene, ending with Tatsuo’s father having a stroke. When his father and his best friend die, it is the prospect of a trip to see the fireflies– promised to him by his father’s old friend Ginzo, who has lost his own son – which keeps him going. Again we have the older generation desperate to offer something to the younger, here a little childish innocence. When his sweetheart, Eiko, agrees to go along, Tatsuo becomes obsessed with the trip. When he reaches the fireflies, however, Tatsuo realises this is the end of his innocence and the beginning of maturity. Soon he will be leaving for high-school, most likely going to a different one to Eiko. The fireflies, that the characters had expected to be a beautiful spectacle, become a sombre sight for each, separately dealing with their own loss.

‘River of Lights’ is by far the longest of the three and because of this offers more depth than the others, but it also suffers from a stuttering narrative and contemplative nature, some of the characters and situations seeming superfluous to the narrative. Set in 1969, the story focuses on two characters: Takeuchi, a retired ageing pool-shark who doesn’t want his son, Masao, to make the same mistakes; and Kunihiko, a young man deciding whether he would like to go to university or stay working at Takeuchi’s bar. Takeuchi’s feelings for Masao are complicated, the taint of his mother’s infidelity passing on to him being something that Takeuchi finds hard to forgive. For Kunihiko, stuck between the quarrelling Takeuchi and Masao, stuck between the past and the future and stuck between staying and leaving, none of his options seem appealing. One transient character puts it all very succinctly: ‘“It gets so that you don’t know whether you’re working just to stay alive, or staying alive just to work.”’ This sentiment, born of the recession but still very relevant in modern Japan, sums up the struggle of Miyamoto’s characters perfectly.

The weakness of Rivers lies in is its use of an overly explanatory tone. Miyamoto seems fond of extensive descriptions to set the scene, but this sometimes overflows into his narrative and goes against the old adage that an author should show and not tell the reader how to think. A glaring example of this is found towards the end of the collection, during a telephone conversation.

‘”I’m at our usual coffee shop right now. It looks as if I won’t be able to see you again for some time, so I’d like to say goodbye…”

Hiromi sounded as if she wanted to meet and have a talk.’

Although this is a particularly obvious instance, there are several that stick out throughout the stories, especially in ‘River of Lights’, which also has quite a number of spelling and grammar mistakes that should have been picked up in editing.

Despite these drawbacks, Rivers is an informative collection that creates an interesting hybrid of the cruel and the nostalgic times of youth. While the heavy description can be a little invasive and a hindrance to the narrative, the plight and growth of the characters is compelling enough for the reader to persevere. At times, even amongst the squalor, the cruelty and the suffering, there are moments of beauty that allow the reader and the characters alike to push forwards.