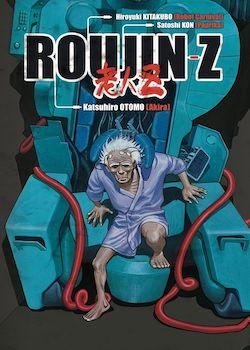

Roujin Z

Directed by Hiroyuki Kitakubo and written by Katsuhiro Otomo

DVD/Bluray (2012), 80 Minutes

Review by Chris Corker

Roujin Z is not a new anime – it was originally released in 1991 – but it is one that has recently been re-released into the public domain, and also one of those rare pieces of filmmaking whose social context is still just as relevant today as it was when it was made. Focusing on the problem of Japan’s ageing population (To quote the BBC: ‘in 1990 (in Japan) there were almost six people of working age for each retiree, but by 2025 that number will have fallen almost to two.’), the film satirically reproduces the mech-orientated glory days of Japanese animation, placing this camp and overblown genre within a serious moral construct. And it does so to great effect, possibly more so for those who are familiar with older animation, while newcomers may just find the whole thing baffling. Perhaps these, however, will find humour in the knowing nod to the early sci-fi, that idealistically prophesised the end of all our problems through the vessel of technology.

If anything could act as a guarantee of the quality the film has to offer, it would be the production staff. Katsuhiro Otomo is one of the few names in anime to be well-known outside of Japan beside Hayao Miyazaki, and his seminal masterpiece, Akira, is still considered to be one of the most influential sci-fi and punk films of all time. The other notable name is that of Satoshi Kohn, who, until his untimely recent death at the age of 46, produced some of the most thought-provoking – and certainly mature – anime ever. Works such as the psychological thrillers Perfect Blue, Paranoia Agent and Paprika, as well as other films such as Tokyo Godfathers and Millennium Actress, are a testament to an impressive body of work. I would argue, however, that his greatest project was born of a second collaboration with Otomo called Memories. Kohn’s segment, Magnetic Rose, perfectly entwines narrative elements such as love, loss and betrayal in the limited arena of deep space, and with only a forty minute runtime. I doubt any other film will ever take the genre of Space Opera – even it if it somewhat of a misnomerin this case – so seriously, or portray it more adeptly. And while Kohn is only really responsible for art and design here, you can see the rudimentary origins of his character design and his attention to detail in play. Otomo-isms are also apparent throughout, most noticeably in the electronic wire tentacles that flail about madly, before connecting in synergy with buildings and computers, creating a network of mechanical veins.

The story takes place in a relatable and recognisable, modern Japan, where the burgeoning population of elderly is becoming a problem for the state. The Ministry of Public Welfare steps in with a solution: the Z-001 bed, which can care for all of an elderly patient’s needs without putting more strain on a nursing force that is already stretched to breaking point. The Z-001 bed is an all-singing, all-dancing computer that seems too good to be true – and here’s where the catch emerges: the power source is nuclear. The basic concept already feels like one fit for anime aimed at young boys (shounen); a bizarre reversal of the Gundam premise, where young children are forced into machines and used as tools of war. Here is where the satire begins. Roujin, in Japanese, simply means an elderly person. We associate the ‘Z’ however, more with shows that involve big shiny robots (as in Mazinger Z) or giant muscled heroes punching each other through mountains (Dragon Ball Z). What we don’t expect, is a social commentary on an ageing society. These layers are where Roujin Z‘s strength lies. It isn’t afraid to be derivative or to make nods to other works that have influenced it, such as in a scene where a hacker boasts he has just infiltrated the Tyrell Corporation, this being the manufacturer of Replicants in Blade Runner. It’s an apt mention, given that the question really running throughout Roujin Z is whether or not a machine, devoid of compassion and other human emotions, can really give the quality of care needed for a human being.

Right in the middle of this troubled setting is Haruko, a student nurse caring for an elderly Mr Takazawa, who will later become our man in the machine. Takazawa yearns for the companionship of his wife, Haru, who we know has already passed away. His yearning is first misdirected towards Haruko (‘Ko’ in Japanese can mean child, placing Haruko as a younger version of the wife that Takazawa has lost) and then the machine, which, through technological trickery imitates her voice. When Haruko realises that Takazawa is to be used as a test subject for the Z-001 she protests, asking the question:

‘How can the machine give him the love he needs?’

This is a question that is later turned on its head, as the machine acts with Takazawa’s desire’s at heart, while the humans in charge of his care, who couldn’t have been said to have treated him with dignity as he was photographed, poked and prodded, try their best to capture him. It is Takazawa’s desires – specifically to return to Kamakura and the daibutsu in Hase, where he spent happier times as a young man with his wife – that cause the machine to revolt, first being encouraged by outside hackers, before gaining sentience. Its escape is chaotic, and here the story takes on the guise of a humour-filled chase sequence, reminiscent of films like Herbie. Adding to the humour of the chase are the central characters, featuring the archetypal roles of the brash, proper but naive official and his quiet, nefarious, fox-faced sidekick.

As the chase continues, the Z-001 becomes more and more emotionally involved with its patient, enveloped in the role of wife and protector. Wedged in here for good measure is a plot involving the use of the Z-001’s chip for the military, but this is overshadowed by the more heart-felt narrative, the constant humour in which prevents the story from becoming too heavy. This levity, however, never detracts from the depth of the story. If we were to dig beneath the surface we may even see Otomo’s rampaging, ever-spreading, unstoppable technology as a clever manifestation of this ageing society, perhaps even of the effects on the planet of our entire population. The final scene brilliantly optimises this bizarre mix of the spiritual and technological, still treating it with a dash of humour.

While the animation may have aged, the social commentary of the film remains as prudent as it ever was, perhaps more so. It also helps that the film is, at its core, a light-hearted – at times almost slapstick – adventure that can be enjoyed by anyone familiar with anime, and possibly even by those that are not.