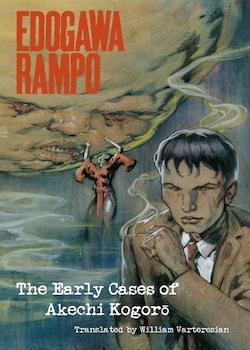

The Early Cases of Akechi Kogoro

By Edogawa Rampo

Kurodahan Press

5 Nov. 2014, 226 pages

ISBN-10: 4902075628

Review by Chris Corker

Edogawa Rampo (1894-1965) is one of the founding fathers of Japanese detective novels. A prolific writer, he wrote over one hundred and fifty short stories and novels in his long career. Like many famous Japanese novelists, he attended Waseda University but studied economics rather than English Literature. Influenced by early translations of Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allan Poe, he became fond of the gritty, dark nature of western murder mysteries. Rampo unashamedly references these works, especially Poe – whose name is anagrammed to create Rampo’s own pen name – in his own stories. This is apt given both authors exhibit a penchant for the grotesque and macabre that can at times discomfort the reader.

The detective, Akechi Kogorō is very much moulded in the image of Sherlock Holmes, on the one hand quick and ingenious, on the other eccentric and haughty. When taken to an extreme, Kogorō’s lack of humility and gloating over even the small victories can wear thin. Perhaps this is because these four stories, each early works that the author condemned as “failures”, do not focus overly on Kogorō, instead preferring to rely, as Conan Doyle did, on a less than brilliant sidekick. Without the requisite column inches, Kogorō is left to revel in his own ingenuity only in brief snatches or bloated denouements. The sidekicks are relatable enough in their way and serve their purpose as narrators that are not privy to all of Kogorō’s dealings, creating an air of mystery. A certain amount of suspension of belief is necessary, however, as they repeatedly choose not to report facts to the police and attempt their own hapless and ineffectual investigations, eventually passing the baton to Kogorō, who fits the pieces together and takes the credit.

There are four cases in all. The first, Murder on D Hill, begins by listing the facts of the case in the style of a police report. The narrator here is a young man out of university but without a job, an acquaintance of Akechi Kogorō. As rumours circulate of women appearing at the bathhouse covered in bruises, the wife of a bookshop owner is found strangled to death. When Kogorō himself comes under suspicion, he must clear his name and point to the real murderer. Both here and in The Dwarf, we find that Akechi takes little pleasure in discovering the murderer and actually sympathises with the culprit.

In The Black Hand Gang a string of abductions and robberies have the city on edge. Amidst the confusion, the narrator’s cousin is taken and his uncle beaten up. When the cousin is not returned even after the ransom has been paid, Kogorō is called in as an advisor. An inspection of the ransom handover point reveals only the uncle’s and the servant’s footprints. This case is the weakest of the collection and its resolution involves a cryptogram based entirely on the Japanese writing system, which gets somewhat lost in translation and will be incomprehensible on anyone not familiar with Japanese.

The Ghost, ostensibly the story of a haunting, stands apart from the other cases. When his fierce rival dies, the successful and wealthy businessman Hirata believes that he can rest easy. His peace, however, is disturbed when he receives a letter from the dead man, promising that he will kill him from the afterlife. Having wronged his rival in the past, the subsequent torment has every indication of being karmic for Hirata, who sees his dead rival’s face wherever he goes. A creepy tale written predominantly from the perspective of the isolated and jittery Hirata, The Ghost is almost entirely bereft of Kogorō until the final pages, the underwhelming conclusion reached with a few simple enquiries.

The Dwarf is the longest and strongest detective story of the four. It does a good job of leading the reader down various avenues of thought, only to be dropped back at the edge of the maze. Amongst the backdrop of a night of vagrancy, arrests and dirt, the narrator sees a dwarf drop a human hand out of his pocket. Following him, he sees the dwarf enter a temple. Returning the next day, however, he finds no-one in the temple or in the local area has ever seen him. Soon after, as a young girl is reported missing, a human arm is found affixed to a mannequin in a department store. When the fingerprints match with those of the missing girl, everyone assumes the worst. Kogorō, however, is not so sure. The Dwarf employs a third-person narrative that switches scenes often, allowing the reader to know things that the protagonists do not, as well as giving them an insight into the criminal’s world. Despite the reader again needing to employ suspension of disbelief as every character except Kogorō flaps about and makes questionable decisions, the conclusion to The Dwarf is far more satisfying than in the other stories.

Where in Murder on D Hill, it was understandable that Kogorō may have felt sympathy with the murderer, in The Dwarf it is almost incomprehensible, also going against his earlier assertions. Throughout the story it is the dwarf who is the contemptible one, his unseemly appearance acting only to highlight his even uglier character. Perhaps a product of its times, political correctness is rarely observed, referring to the dwarf as both ‘a deformed child’ and his face as ‘a wasp spider that had been crushed by a foot.’

Ugliness is a staple of Rampo, however – he is fascinated by it, often juxtaposing it with beauty, blending the grotesque and the erotic.

‘{…} he also had a desire, like an ache, to see the lady’s flustered condition alongside to that hideous dwarf.’

It’s difficult to recommend The Early Cases of Akechi Kogorō as an entry point to the works of Edogawa Rampo. It is explained in an introduction that focuses heavily on the merits of later work, not available here, that the character of Kogorō here bears little resemblance to the one that readers have come to love in literature and film. While The Dwarf does do a good job of building tension and deceiving the reader until the last, the other three stories feel rushed, the revelation of clues feeling more like a statement of facts rather than a source of surprise. A few spelling and grammar mistakes also break the flow of the narrative, along with some confusing dialogue where the interlocutor is not clear.

Anyone already familiar with the Kogorō series may enjoy seeing the origins of the character, but newcomers should look to better-known works. Lovers of bizarre mysteries and the grotesque may find something to love here and The Dwarf, in particular, is a sound and sometimes intriguing story. Despite this, it’s hard to argue with author’s condemnation of his own stories.