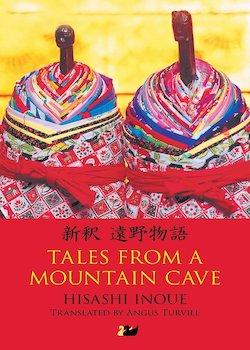

Tales from a Mountain Cave

By Inoue Hisashi

Translated by Angus Turvill

Thames River Press, 2013

ISBN 978-0-85728-130-2

Review by Jack Cooke

A lone trumpet call reverberates across the mountain valley and our story begins . . .

If you have ever fallen asleep on an idle summer’s afternoon and had one of those dreams that seems to encompass whole years instead of a few passing hours, awaking disorientated and curiously melancholy, then you already know what it feels like to turn the last page of Tales from a Mountain Cave and re-enter the world; in my case a cold, grey London in December.

The tales are set in the Kamaishi area of Iwate Prefecture. The region’s twentieth century history, one of industrialisation and mining, offers a stark contrast with its folktale past, yet this thin veneer of modern life cannot repress the enduring legends that lurk beneath it. The period in which the stories are set seems just within our reach and simultaneously elusive, ever-present but masked by the dramatic transitions of the last one hundred years.

The structure of Tales from a Mountain Cave involves a tale within a tale, a jigsaw compilation of the mysterious story-teller’s persona, an old man living in the mountain cave of the title, and that of his avid listener the narrator. The absorbing atmosphere this creates is akin to a daydream; where fact and fiction freely intermingle. This mood is reinforced by the mixing of a plausible present, the 1950s ‘real-time’ in which the tales are related to our narrator, a student working in a Tohoku sanatorium, with the fantastical past of the old man’s life. One curious way of looking at the plot is to view it as analogous to the composition of magnetite, the mineral that the region’s mines are famed for. Parallel lattices of fact and fable intertwine, splicing elements of Inoue’s own biography with the accumulated legends of Iwate’s written and oral histories.

In what other story collection is the reader led through such a kaleidoscope of myth? Foxes fornicating with women, wayfarers running from cannibalisation, a giant eel disguised as an accountant; these and other such wonders represent a small cross-section of the varied legends that lie within. One particularly mischievous story relates the deeds of a beautiful seductress inhabiting a hillside grove. The scene conjured by the storyteller has the reader joining the protagonist peeping through a hole in the screen of this woman’s house, watching as she entices a passing traveller. The voyeuristic appeal of the story makes us eager to enlarge the view through the hole but, at the climax of the tale, we find the vision that has held our mind’s eye is not at all what it seems. Such shifting perspectives abound throughout the book.

Inoue Hisashi was renowned for his humour, both in his work as a playwright and as a novelist. At the outset of the book the author quotes from an earlier collection of folktales, Tono Monogatari by Kunio Yanigata (translated as Legends of Tono by Ronald A. Morse, 1975), from which Tales from a Mountain Cave draws some inspiration;

‘I believe there may be hundreds of such stories in the Tono area and their dissemination is greatly to be desired . . . legends that the people of the plains will shudder to hear.’

Inoue then contrasts this with his own rejoinder:

‘I expect there are hundreds of stories like this around Tono. I have no particular wish to hear them, but I am sure that such tales of mountain spirits and mountain people may serve to tickle the people of the plains.’

Married to the author’s self-deprecation and mockery is his stated aim to ‘tickle’ the reader rather than induce a ‘shudder’. However, I often found the two inseparable. Mountain men, kappa, fox spirits; the appearance of these in Tales from a Mountain Cave is every bit as frightening as the interpreted legends of Akutagawa Ryūnosuke or Lafcadio Hearn. In the book’s darker moments we find tragic and grotesque spectacles; a pair of lovers’ cliff-top suicide or the body of a disembowelled child. These instances of the macabre are contrasted with abundant comedy throughout, often centred on a sense of the absurd, such as this curious line:

‘. . . I was material to be at least a doctor of some level, if not a fully fledged quack then perhaps at least some kind of quackling.’

Bound up with Inoue’s humour is a focus on the playful nature of animal spirits, central to many of the concepts expressed in Japanese belief systems. The combating of human and animal nature, in which the latter nearly always prevails, is a consistent theme in the tales. Human violence often gains the upper hand but it is animal guile that has the last laugh; the protagonists, the narrator and, by association, the reader, are all fooled time and again. The final example of this comes at the book’s conclusion, a twist in the ‘tail’ well worth waiting for.

Inoue himself once worked in a sanatorium in Kamaishi. How wonderful it is to reflect on him sitting on the mountainside and concocting the tales that form this book; imagine the author, with his trademark grin, perched somewhere high-up above his daily labours and daydreaming this collection into existence.

The translator, Angus Turvill, has visited many of the settings found in Tales from a Mountain Cave. All royalties and translation fees from the book are going toward projects aimed at rebuilding the parts of Iwate that were so terribly damaged by the events of March 2011. There is a touching symmetry in the idea of a local book, first penned some thirty-eight years ago, now aiding the very place of its conception in a time of need. Turvill has distilled something very special in this reworking of Inoue’s original and in his acknowledgements we find an exemplary panel of readers, editors and well-wishers. Those involved with the book, however obliquely, range across the full spectrum of Japanese translation. It is reassuring, both in literary and human terms, that so much of this community should come together to support a worthy project.

Turvill mentions in his introduction to the translation that, ‘The building where the author lived with his mother in the 1950s was one of the many to be swept away (by the tsunami).’ Inoue, who died in 2010, a year before the Great East Japan Earthquake, would be pleased to find that, though many things in this world are transient, his collection of stories has now reached beyond the ‘people on the plains’ and found a global audience.