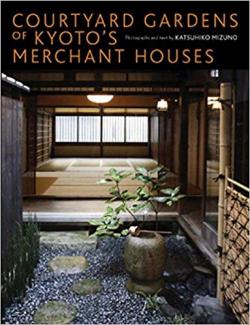

Courtyard Gardens of Kyoto's Merchant Houses

Photographs and text by Katsuhiko Mizuno

Translated by Lucy North

Kodansha International, (2006)

ISBN: 4770030231

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

This is a book which will fascinate all lovers of Japanese gardens. It provides an introduction to the tiny gardens, generally referred to as tsuboniwa, incorporated into Japanese houses in Kyoto. These, unlike temple and palace gardens, are not normally open to visitors. A tsubo is a Japanese measurement of a small area approximately 35.5 feet square. Not all tiny gardens were necessarily of this size but the term underlines the small scale of these gardens.

In his preface Mr Mizuno explains that these gardens were developed as essential parts of the typical Kyoto town house or machiya. In the late sixteenth century merchants built single storey wooden houses along the sides of the streets of the capital. These had a narrow frontage on the streets as taxes were assessed on the width of a house's façade, but extended a long way to the back. The tsuboniwa were built to provide greenery and air, so essential in a hot climate such as that of Kyoto in summer. Mizuno points out that the heart of the machiya architectural design was "the desire to live as much as possible in harmony with nature - to treat it with respect and affection, at the same time as fully utilizing its blessings and gifts." Machiya are "dwelling places that are gentle, both to nature and to human beings who live in them."

It is difficult to choose some typical examples from such an excellent collection of photographs, but here are some which I particularly liked. The inner garden of the Shikunshi, a kimono shop, is simple and refreshing (page 18). The intermediate garden of Yuzuki, an accessories shop, is a tsuboniwa "best described as a walkway that connects the front rooms of the house with the rooms in the wing behind (page 25)." The rear garden of Suzuki Shofudo (maker of paper products) has (page 39) "an Oribe lantern and several streaked green stones…on a gourd-shaped carpet of hair moss" with a bamboo fence "whose light colour echoes the Shirakawa gravel." In the main garden of the Shiraume, a traditional Japanese inn (page 52), all the stone features are small and low creating an "overall effect, both graceful and spacious." The front garden of the Tamura residence (page 116) filling "a simple rather shallow rectangle… necessitated a very simple design, a well corb made of Shirakawa stone…a medium-sized washbasin, stepping stones of Kurama rock, and…small evergreen bushes. The result is light and open."

There are many other photographs to delight the eye and make the reader wish that he could not only revisit Kyoto but also somehow arrange private visits to a few of these houses with their charming little gardens.