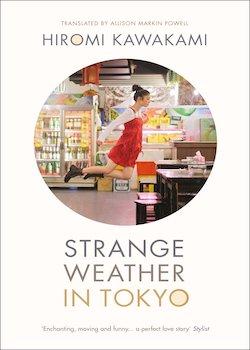

Strange Weather in Tokyo

By Hiromi Kawakami

Translated by Allison Markin Powell

Portobello books (2013)

ISBN-10: 1846275083

Review by Susan Meehan

Hiromi Kawakami won the Tanizaki Jun’ichiro Prize for her best-selling novel Sensei no Kaban (Strange Weather in Tokyo (UK edition) or The Teacher’s Briefcase (USA edition) in 2001. In 2003 the story was adapted for television by the writer and director Teruhiko Kuze.

I am not surprised by these accolades, for Strange Weather in Tokyo is an understated, poetic, gentle, profound, thoughtful, poignant, beautiful book centring on the friendship between Tsukiko Omachi and Harutsuna Matsumoto. They both frequent the same small bar near a Tokyo station. Having noticed her and their shared taste in food and drink, one day Mr Matsumoto addresses her, wondering if she is indeed Tsukiko Omachi. It dawns on Tsukiko that this gentleman had been her Japanese teacher at secondary school. As she did at school, she refers to him as ‘Sensei’.

37 year-old Tsukiko and 67 year-old Sensei forge a friendship around encounters at the bar. They never arrange to meet there, but are always happy when they meet by chance. They both enjoy their drink.

Sensei is old-fashioned, didactic and often upbraids Tsukiko on her unladylike behaviour while Tsukiko enjoys listening to Sensei recounting haiku or telling her about his collection of teapots. She is unaffected, refreshing, modern, capricious and quirky.

Tsukiko had not excelled in Japanese at school, but as an underhanded compliment Sensei commends her on being ‘an excellent student when it comes to drinking.’ Their research into drinking is key to their friendship.

Both Tsukiko and Sensei live alone. He is a widower and she is single. They are both rather obstinate. When it comes to drinking he doesn’t like being poured for, though Tsukiko insists at times, much to his irritation. She is a lousy pourer anyway, with no interest in learning from Sensei how to pour well.

Tsukiko struggles with her stubbornness and awkward behaviour. On one occasion she cannot bear talking to Sensei any more as he gloats over the victory of his baseball team, The Tokyo Giants, over their perennial rival, the Hanshin Tigers. Tsukiko had never realised quite how profound her dislike of the Giants was, gritting her teeth at Sensei’s delight, cursing and wondering why Giants’ fans are so ubiquitous. She is such a child and Sensei is taken aback by her stroppiness.

Perhaps the secret to their friendship is the difference in age. As Tsukiko herself recognises, she is somehow becoming more childlike as she ages, having been rather grown up when she was at primary school. She doesn’t ‘seem able to ally herself with time.

Each chapter of the book is like a haiku, incorporating seasonal references to the moon, mushroom picking and cherry blossoms. The chapters are whimsical and often melancholy, but humour is never far away.

As the novel progresses Tsukiko once again defiantly avoids Sensei. He annoys her so much – albeit unwittingly – and Tsukiko hopes that distancing herself from him will ensure she gets over the co-dependent drinking partnership that has become routine and which is cramping her style.

There is no real surprise as to how the book unwinds, but this does not make it any less enjoyable. It continues to spellbind, and the book’s gentle yet powerful sentiment lingers on with the reader. It is a celebration of friendship, the ordinary and individuality and a rumination on intimacy, love and loneliness.

I cannot recommend Strange Weather in Tokyo enough, which is also a testament to the translator who has skilfully retained the poetry and beauty of the original.