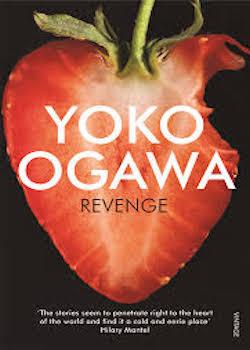

Revenge

By Yoko Ogawa

Vintage

3 July 2014, 176 Pages

ISBN-10: 0099553937

Review by Chris Corker

Yoko Ogawa is a well-established and highly respected author in Japan, who, to quote from her profile at the start of this taut book of short stories, ‘has won every major Japanese literary award including the Akutagawa and the Tanizaki prizes’. Ogawa is now in her 50s, and these stories certainly have the marks of a confident author in free-flow. There is an undeniable beauty of narrative in each tale and in the discreet connections that bind them together as a coherent whole.

Ogawa seems to be an author who is more comfortable with the short story and novella genres that make up the majority of her oeuvre, rather than more extended prose, and this work, despite containing a total of eleven stories, stands only at a well-spaced 176 pages. Still, it is hard to complain when the stories are crafted so meticulously, with an economy of prose that often cuts right to the heart of the matter. On occasion, however, she does have a tendency to rush ahead with the narrative with such vigour that the dramatic impact is lost, a build-up of tension impossible.

Rather than a collection of randomly selected short stories, the tales that comprise Revenge have a broader significance to one another, generating a sense of co-dependence that gives birth to a narrative greater than the sum of its parts. In a manner somewhat reminiscent of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, the stories hop through various times and places, and their connection to each other is not always immediately apparent; the desire to find out how each story is interlinked generates a pleasant page turning anxiety not often found in the short story genre.

In ‘Afternoon at the Bakery’ a woman waits for a baker to return so that she can buy a strawberry shortcake for her six-year-old son, who died twelve years ago inside a fridge. As she waits she recollects the aftermath of his death. This story, like many others in this collection, is about not just the cruelty and indiscriminate nature of death, but also its loneliness – symbolised here by the dark, cramped fridge – both for the deceased and their loved ones. The strawberries on the shortcake are at first ripe and vivid, but quickly discolour and wilt. This story has a strong sense of place and transports the reader smoothly into a Japan of cats, drinking fountains and snap-happy tourists. The woman inside the bakery, though, is alone, separate from that world. The next story, ‘Fruit Juice’, also features bereavement and concerns a girl who, left alone by the death of her mother, goes to see the father who abandoned them. It is not obviously connected to ‘Afternoon at the Bakery’ at first, but we eventually learn that they share a common character, despite their chronological displacement.

‘Old Mrs J’ – my favourite story within the collection – is a dark, modern and discreetly sinister fairy tale. A writer – who features in many of the stories in a metafictional role – is intrigued by her new landlady, who seems at times to be elderly and infirm, and at others able and nimble. One day she gives the writer a carrot in the shape of a human hand. Soon after, more and more of these carrots, replicas of the first, are gifted to everyone in the building. This story – redolent of the Succubus myth – builds up tension very well and maintains its intrigue until the end. In the next story, ‘The Little Dustman’, a young girl is sat on a delayed train on her way to the funeral of a writer.

For ‘Lab Coats’ Ogawa favours a present tense reporting style. Here we are introduced to another common theme in Revenge: the irrational power of obsessive – sometimes unrequited – love. It is portrayed as a blind feeling that will forgive even the most despicable acts. In the morgue of a hospital, two characters – one in love with the other despite their cruel personality – itemise soiled lab coats. One of them is building up to a confession of love, the other to a much darker revelation. Briefly revisiting the same hospital is the protagonist of ‘Sewing for the Heart’. In this cleverly metaphorical tale of human isolation, a bag maker is commissioned to make a pouch for a woman whose heart hangs externally at her side. ‘Sewing for the Heart illustrates’ how a seemingly noble act can turn quickly sour, how love can be dangerously possessive:

‘I wondered what would happen if I held her tight in my arms, in a lover’s embrace, melting into one another, bone on bone… Her heart would be crushed. The membrane would split, the veins tear free, the heart itself explode into bits of flesh, and then my desire would contain hers – it was all so painful and yet so utterly beautiful to imagine.’ Pg 69.

The subsequent stories build on these same themes and delve into the part of the human psyche that finds interest in the macabre, as well as the connection between sadism and eroticism, love and hate. Another constant is the fear of the speed of death and of non-existence (‘Why was everyone dying? They had all been so alive just yesterday.’ Pg 78). Thematically, all of the stories fit snugly together to create a foreboding collage of the futility of human relationships. And yet there is a vein of quietly optimistic beauty that runs through each page, preventing the collection from leaving one numb.

The book is not without its faults. I found the voice of the male protagonists far less convincing than their female counterparts; the voice differs very little from story to story, and without a clear identification of gender, I found I was sometimes confused as to the relationship of certain characters.

Some readers may also find the cruelty and violence in these stories – sometimes rendered more acute for being perpetrated by young girls – exaggerated, stepping outside the realms of the believable. Yet we have only to look at the recent case of the schoolgirl in Sasebo, who beheaded her classmate and cut off her wrist because she “wanted to dissect someone”. Sasebo had already seen a similar incident in 2004 when a schoolgirl killed her classmate, and In 1997 a 14-year-old student killed two of their classmates in Kobe, leaving the head of one at the school gates. It may be uncommon, but the cruelty is there, and nothing here eclipses that horrifying reality.

Prior to Revenge I hadn’t had a great success rate with Japanese fiction by female authors. I found Natsuo Kirino’s Out to be perfectly readable but misandristic in theme and so angry as to be caricatured; in contrast, I found Banana Yoshimoto’s Kitchen sickly-sweet and melodramatic. It was a pleasant surprise then that I found in Revenge something intriguingly dark in tone, but also familiar and comforting, something sinister but not depressing. Some of the stories do stand head and shoulders above the rest – I found ‘Lab Coats’ the weakest of the bunch – and the breathless nature of the narrative sometimes betrays the otherwise carefully established atmosphere. Having said that, I also have to admit that these stories are at times masterpieces of the sinister undertone. In all, this is a work that benefits from its sparseness and implies a world and narrative much wider than the one on the page.