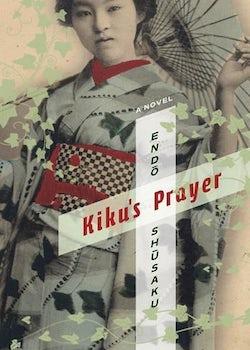

Kiku’s Prayer

By Shusaku Endo

Translated by Van C. Gessel

Columbia University Press (2013)

ISBN: 978-0231162821

Review by Suki Maw

Endo’s Faith – Religious Persecution and Kiku’s Prayer

Kiku’s Prayer is an English translation of Shusaku Endo’s novel Onna no Issho: Ichibu – Kiku no Baai (Woman’s Life: Volume I – Kiku’s Case), first published in 1982.

Shusaku Endo (1923–1996) was a Japanese novelist born in Tokyo. While many of his light-hearted, humorous works are widely read in Japan, he is particularly highly regarded for his serious novels with strong Catholic themes. (His literary work is sometimes compared to that of Graham Greene.) Following the divorce of his parents at the age of ten, Endo was baptised into the Catholic Church on his mother’s persuasion. However, his spiritual journey was not a smooth one. Finding it incongruous to be a Japanese and a follower of the Western religion at the same time, he formed the view that the cultural and ideological milieu in Japan was such that it did not allow the Christian faith to truly permeate among the Japanese, and the “clash” between Japan and Western Europe in religious and ethical contexts became one of the main themes in his literary work. At the same time, Endo’s literary work features a focus on “weak” or “cowardly” individuals, and a “compassionate” image of Christ developed and embraced by the Japanese. On this point, Endo’s analysis was that, the image of “compassionate Christ” was developed in Japan by those who sought forgiveness for ostensibly abandoning their Christian faith for fear of torture and death under persecution.

In Kiku’s Prayer, Endo insightfully depicts the characters in different situations amidst the persecution of the Christians in Urakami, a suburb of Nagasaki, during the turbulent years of the latter half of the nineteenth century. While Kiku’s Prayer is a fiction, the novel incorporates meticulous research conducted by the author, and contains accurate accounts of the historical events as detailed below, along with the names of priests, political figures, places and buildings.

Christianity was introduced to Japan by Francis Xavier, a Jesuit, in 1549. The number of Christians in Japan, or Kirishitan – the word referring to the Japanese Catholics until the lifting of the ban on Christianity in 1873 – is estimated to have been as high as 600,000 circa 1600 (approximately 2.4% of the country’s population). However, following the shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s abrupt order to expel the Jesuit missionaries from the country in 1587, the Tokugawa shogunate imposed a total ban on Christianity in 1614. Within the country, a strict anti-Kirishitan policy was maintained throughout the remainder of the Tokugawa era, a period of some 250 years. Under this regime, ferocious attempts were made to eradicate Christianity altogether by means of torture and death. (For example, some Kirishitan who refused to renounce their faith were thrown alive into a volcano in Nagasaki.) Also, systematic methods were employed for suppression, including trampling on sacred Catholic images by all subjects in front of government officials and the compulsory registration of all subjects as parishioners of their local Buddhist temples.

However, a few months after the completion of Oura Catholic Church – the church built for the French Catholics residing in Nagasaki – in 1864, Fr Bernard-Thadée Petitjean had a dramatic encounter with a group of Kirishitan from Urakami. While Tokugawa’s anti-Christian edicts were still strictly in force amongst the Japanese, to Fr Petitjean’s astonishment and joy, these Urakami Kirishitan confided in him that they shared his faith, and were overjoyed to see the statue of Virgin Mary with “Baby Zezesu” in her arms. This implies that, remarkably, Christianity had not been extirpated in Japan in spite of the severe anti-Kirishitan policy for over 250 years.

In fact, while having to abandon all the outward manifestations of Christianity, groups of Japanese Christians had clandestinely preserved their faith for two and a half centuries, despite having no access to a priest, the Church or the Bible, and of course, at the constant risk of death. Kirishitan skilfully developed their own ways of practising their faith, and passed the teachings from one generation to the next. For example, Maria Kannon, images of Our Lady in the guise of a Buddhist deity, were created, and secret posts were assigned within underground communities to baptise the children (called “mizukata”) and to communicate the Church calendar (“chokata”).

Following Fr Petitjean’s dramatic discovery of the “hidden Christians” at Oura Catholic Church, the Urakami Kirishitan grew increasingly expressive of their faith. In 1867, they went as far as to collectively express their wish to no longer have any dealings with the Buddhist temple at which they were forced to be registered. Bewildered, the local magistrate reported the “resistance” of these Kirishitan peasants to the central government. The newly formed Meiji government’s decision was to exile the entire village of Urakami, in spite of the fierce criticism and protests from Fr Petitjean and Western diplomats. In total, over 3,000 Urakami Kirishitan were exiled to various places within Japan, including Tsuwano in south-western Honshu, where particularly harsh tortures were inflicted upon them. In fact, the Urakami Kirishitan had endured three crackdowns previously. However, this fourth crackdown became the most extensive one.

The political situation in Japan was dramatically changing. In 1868, the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown, and the Meiji government was formed with the emperor restored to the throne. As a consequence, along with the collapse of the Tokugawa era’s feudal system, the samurai ruling class with hereditary privileges had been abolished. In Kiku’s Prayer, their fate and the drastic changes to the country’s political and social hierarchy are skilfully depicted in the contrast between two individuals, Ito Seizaemon and Hondo Shuntaro.

In the novel, Kiku, a self-assured peasant girl in Urakami, falls in love with Seikichi, a young peddler from another district of Urakami and a devout Catholic. While she witnesses Seikichi quickly make “some strange gesture” at the entrance of Oura Catholic Church, Kiku knows virtually nothing about Christianity. When the Tokugawa era’s abhorrence of Kirishitan in society in general was still prevalent, it is not surprising that, to Kiku, a bright yet uninformed country girl, Kirishitan – mocked as “Kuro” (meaning “black”) were “strange people” who held “pointless beliefs”. In fact, she associated the word Kirishitan with criminals on death row, if not simply with death. However, instead of abandoning his “evil Kirishitan faith” as Kiku wished, Seikichi begins to optimistically assume that Kirishitan have now become able to publicly express their faith with the demise of the feudal ruling elite on the arrival of a new, emperor’s era. However, he was completely wrong. Contrary to his complacency, Seikichi is exiled to Tsuwano in the fourth Urakami crackdown. During Seikichi’s exile, Kiku becomes determined to alleviate his misery, and is moved to great self-sacrifice. The single-minded efforts she makes for Seikichi are painful. Despite Kiku’s ignorance of Seikichi’s “stupid religion”, the novel has a profound religious climax.

I have said earlier that one feature in Endo’s literary work is the focus on “weak” or “cowardly” individuals. In Kiku’s Prayer, the contrast is stark between the self-confidence of the sharp, ambitious Hondo Shuntaro, a government interpreter, and the clumsiness and tactlessness of Ito Seizaemon, a lower-ranking Nagasaki official and a persecutor of Kirishitan himself.(“A pathetic soul” in contemptuous Hondo Shundaro’s words.) However, it is worth noting that, in the author’s afterword, Endo confesses that he “began to sympathise with this despicable man – and [that he] felt not just sympathy but even a love for him”. The author further explains that “[u]p to the very end of the novel [he] couldn’t bear to forsake him”. This is perhaps why Endo had Fr Petitjean say to Ito that God loved him more than he loved Hondo Shuntaro. Overall, the role that this dishonest, cowardly yet complex man plays in the novel seems no less important than that of the eponymous Kiku.

Van C. Gessel, the translator of the book, was a professor of Japanese at Brigham Young University in Utah at the time of the translation. He became renowned for his work as the primary translator of Endo’s works. On the whole, Kiku’s Prayer is a faithful translation of Oura no Issho. In addition, the footnotes added in Kiku’s Prayer will prove useful to readers in gaining background information on some political figures. One disappointment in Kiku’s Prayer, however, is the absence of the nuances which the regional dialects convey in the original novel Onna no Issho. A reader of the Japanese novel will notice, for example, that the distinctive Nagasaki dialects are spoken by Kiku, Seikichi and Ito Seizaemon, while Our Lady at Oura Catholic Church and even Hondo Shuntaro, who started his career as a lower-ranking Nagasaki official like Ito, speak “standard” Japanese. While perhaps inevitable that this point was compromised, the Nagasaki dialects certainly add a distinctive flavour to Onna no Issho. In fact, in the first line of the author’s afterword, Endo explains that Onna no Issho was an attempt to repay some of the indebtedness he felt towards Nagasaki. Kiku’s Prayer is not free from apparent translation errors, omissions and typographical errors. For instance, Yokohama and Nagasaki, north-western and south-western Honshu, and younger and older sister are confused. Also, it is particularly puzzling why Jinzaburo Moriyama, an Urakami Kirishitan who was actually exiled to Tsuwano in the fourth Urakami crackdown, is referred to as Kanzaburo Moriyama throughout the book. However, the overall faithfulness of the translation more than compensates for these slips and inconsistencies.

Kiku’s Prayer contains strong Catholic themes, and a reader without a Catholic faith or an appreciation for it might find it difficult to empathise with the devout Urakami Kirishitan. Nonetheless, Kiku’s Prayer will appeal to a wider audience just as Onna no Issho does to Catholics and non-Catholics alike in Japan, thanks to Endo’s ingenious and insightful depictions of human virtues as well as their failings in the novel.