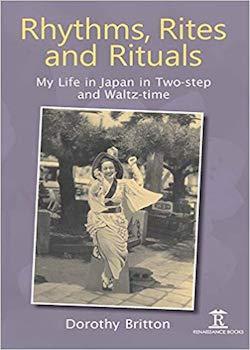

Rhythms, Rites and Rituals: my life in Japan in two-step and waltz-time

By Dorothy Britton

Renaissance Books

2015, 256 pages

ISBN 978-1-898823-12-4

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

What a wonderful title! And what an interesting story Dorothy has to tell!

Dorothy Britton was born in Japan on Valentine’s Day in 1922. Her father was a British engineer whose life she has described in her portrait of him in Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits, Volume VI, [edited by Sir Hugh Cortazzi, Reviewed in Issue 10 – Vol. 2, No. 4]. Her mother was American.

Dorothy was a baby in Yokohama when the city was destroyed in the devastating Kanto earthquake of 1923. She and her parents survived and her mother managed to get on board a ship, which took them to Kobe. After a few weeks in Kyoto they were able to rejoin her father who had worked hard to help the victims of this natural disaster.

She learnt to speak Japanese from her earliest days and first went to school in Yokohama. After her father’s early death, she had a couple of years at an English boarding school where she was scolded for spending her free time studying a Japanese school text book instead of improving her Latin. She later went on to school and college in the United States, but also spent some time in Bermuda, where she became a keen yachtswoman. There, after the outbreak of the Second World War, she was employed for a time as a postal censor, although her knowledge of Japanese characters at that time was limited.

Dorothy had a good ear, which helped her to be bilingual in English and Japanese and enabled her to speak French fluently. Her sense of rhythm and her natural appreciation of sound nourished her love of music and poetry. At Mills College in the United States she studied composition under the French refugee composer Darius Millhaud. She learnt to play the piano, the ukulele and the harp. She wrote poems from an early age.

At the end of the war she and her mother returned to England and for a time Dorothy worked for the Japan Service of the BBC. They longed to return to Japan where the seaside cottage, which her father had built on the coast at Hayama, had been taken over as a beach house by the British Embassy. Eventually they were granted visas by SCAP (Supreme Commander Allied Powers) and in due course they were enabled to take possession once again of their beloved cottage where Dorothy could swim and add to her collection of shells. Dorothy was at that stage in her life employed as librarian in the British Embassy and later in the British Council.

I will not attempt to summarize her later life, which involved much travel around the world and various romantic episodes. She recounts these with admirable frankness. One long-lasting and fraught affair was with the famous Japanese composer Ikuma Dan [團 伊玖磨] whose opera she translated and whom she nearly married. Her attachment to Cecil (‘Boy’) Bouchier, whom she eventually married after his wife died, began when Bouchier (Air Vice-Marshal Sir Cecil), who had been commander of the air contingent of the British Commonwealth Occupation Forces in Japan (1946-48), was the representative in Tokyo of the British Chiefs of the Defence Staff.

Sir Cecil had a son, Derek, who had had a tragic accident as a child. The brain injury which Derek suffered meant that he could not talk. Cecil was devoted to his son but feared that Derek’s life would prevent him from marrying again. Dorothy however immediately felt great affection for Derek and has looked after him devotedly since Cecil Bouchier died in 1979.

Dorothy’s memoir, apart from being a frank and moving record of her peripatetic life bridging the three cultures of Britain, America and Japan, has much to tell the reader about her contributions to cultural interchange through her inspired compositions and fluent translations including her version of Basho’s Oku no Hosomichi.

During her long life in Japan, Dorothy developed friendships with Japanese in all walks of life from the Empress to the local fishermen. She also has much to tell her readers about Japanese life and customs including marriage. (On one occasion Japanese friends arranged a formal Miai with an American for her, but neither participant took it seriously). She was much impressed by what she saw of the Suzuki method of teaching young children to play the violin and thought that language teachers should try to use similar techniques. Dorothy herself helped improve the teaching of English in Japan by her recording sessions with NHK. She also learnt to appreciate the Japanese ability to remain silent when we feel the need to keep up a conversation. She notes that the art of English party conversation, which she taught for a time at a women’s university in Japan, was quite new to the Japanese.