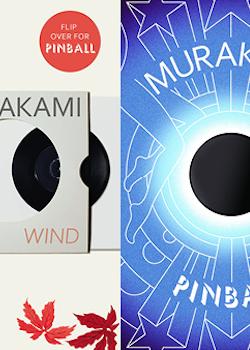

Pinball/Wind

By Haruki Murakami

Translated by Ted Goossen

Harvill Secker

4 Aug. 2015, 336 pages

ISBN-10: 1846558352

Review by Chris Corker

These two novellas, available for the first time in English outside of Japan*, were Haruki Murakami’s first works. They form the first two parts of the informally named Trilogy of The Rat, which concludes with the critically-acclaimed Wild Sheep Chase. Murakami affectionately refers to Wind (full title Hear the Wind Sing) and Pinball – both a little more experimental and rough around the edges than his later works – as his ‘kitchen table novels’, written in brief snatches after finishing work at his jazz club. Despite the difference in style between these formative works and his mature oeuvre, however, the themes are unmistakable as Murakami: a misanthropic loner with a dry sense of humour bobs along in an ocean of jazz, sex, booze, cigarettes and fleeting liaisons with other misfits. Readers are naturally divided as to whether this easy familiarity is one of Murakami’s strengths or weaknesses.

Murakami now has an almost unparalleled fan base, indomitable in its calls for him to win a Nobel Prize. In Japan, at least, there is no author more famous, and on the international stage he is Japanese fiction. Yet it could have been a very different story. In an interesting introduction comprising autobiographical shorts, Murakami tells us that had the first novella, Hear the Wind Sing, not won the Gunzo Literary Prize, his aspirations of being a novelist would have ended there. The manuscript he submitted – in the age of the typewriter – was his only copy, and the prize did not return unsuccessful entries. Also of interest here is a description of the author’s methodology. Unhappy that his early drafts were florid, he resolved to write the first two chapters in English before translating them back into Japanese. Thus his economic and fluid style was born, bucking the trend of other famous Japanese authors such as Yasunari Kawabata and Jun’ichiro Tanizaki.

In Hear the Wind Sing our unnamed narrator is back from university for the summer, whiling away his time in J’s Bar with the trilogy’s titular character, The Rat. There is always the nagging feeling that they are in a sense doubles leading parallel – albeit disparate -lives. In Hear the Wind Sing The Rat is only given reality with the return of the narrator. In Pinball they are dealt with separately, although their fates still seem shared, and again there is the sense that the disparity in their lives is the product of minute chance rather than anything more profound.

J’s Bar provides a backdrop for the character’s reminiscences about their youths – their sexual conquests and the times they’ve been drunk. Philosophy rears its head in-between mouthfuls of beer and peanuts, and as is often the case with Murakami, transience is a common theme, peripheral characters coming and going ‘like a summer shower on a hot pavement’.

Written in a casual and punchy style, Hear the Wind Sing is easy to read and often funny. It feels very much like a first novel, crammed full of ideas and thirty years of life experience. At times Murakami’s innovations feel a little forced – there is one short chapter comprised of Beach Boys lyrics – but on the whole it remains refreshing. The humour is at times extended to serious topics. Mentioning The Rat’s father’s dubiously effective but versatile and popular liquid formulas, the narrator notes:

‘In other words, the same ointment slathered on the heaped bodies of Japanese soldiers in the jungles of New Guinea twenty-five years ago can today be found, with the same trademark, gracing the toilets of the nation as a drain cleaner (Page 100).’

This quote, with its meaninglessness blended with dry, dark humour, is a good representation of the novel as a whole.

Pinball takes place three years after Hear the Wind Sing. The still nameless narrator has moved to Tokyo where he makes his living as a translator while living with identical female twins. In contrast to this phallocentric fantasy is the plight of The Rat, who has remained in their hometown. In an unfulfilling yet apparently addictive relationship, he drives around the town for something to do, always finishing up at J’s Bar. These sections are the weaker of the two parts of the novel. Gone is the fluidity, replaced by an overly descriptive style, in which similes and metaphors run rampant.

In Pinball’s stronger half, the narrator dwells on the memory of an old girlfriend who killed herself, her reasons a mystery. In his visits to the past, he remembers a pinball machine on which he used to play in J’s Bar, and becomes fixated on the idea of playing again. When he finds that the machine is incredibly rare, he goes on a frenzied search. A book he reads gives him an insight into the emptiness that drives him:

‘No, pinball leads nowhere. The only result is a glowing replay light. Reply, replay, replay – it makes you think the whole aim of the game is to achieve a form of eternity.’

Pinball paints a picture of early adulthood characterised by anonymity and loss, and is not always as fun to read as Hear the Wind Sing. It remains intriguing in parts, though, and the atmosphere of decline and dissolution is perfectly apt for the death of childhood dreams.

Murakami fans will find enough familiar elements here to feel at home, yet this is also this collection’s weakness. Murakami himself doesn’t rank these novellas very highly in his oeuvre, which is surprising for one reason: Murakami hasn’t really changed as a writer since 1979, when Hear the Wind Sing was written. You’ll find mentions of wells aplenty, as well as baseball and the other stalwarts of jazz and women with apparently alluring physical deformities. It’s in the early stages, but it is all there. There are also elements that seem to have been directly recycled for Norwegian Wood, such as an ill-fated girlfriend named Naoko and a belief that books by dead authors are the only ones worth reading. If the reader can accept that as their lot, then they will find this collection enjoyable. Hear the Wind Sing especially, thanks in no small part to Goossen’s great translation, is a joy to read. If, however, you are looking for a book that says something new about the author, this would not be the place to start. In these novellas, as in his later works, Murakami writes Murakami.

* The books were previously available in Japan in English, in an edition translated by Alfred Birnbaum and published by Kodansha, intended for Japanese students of English.