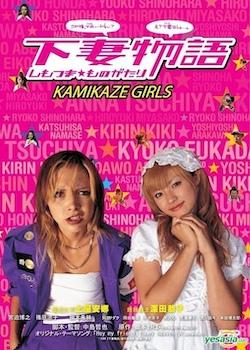

Kamikaze Girls

Directed by Tetsuya Nakashima

2004, 102 minutes

DVD release: January 2009

Review by Simon Cotterill

“Kamikaze Girls” won Best Picture and Best Director at the 27th Yokohama Movie Awards, and its two lead actresses, J-pop stars Kyoko Fukuda and Anna Tsuchiya both attracted numerous plaudits, including nominations by the Japan Academy for outstanding performances. That said, Kamikaze Girls is nothing like a typical award-winning picture.

Despite its English-language title, “Kamikaze Girls” actually has nothing to do with war, pilots or even women taking on traditionally masculine roles. The literal translation of its Japanese title is ‘Shimotsuma Story’, and the film is set in this quiet, rural town in Ibaraki Prefecture. In the eyes of young Momoko (Fukuda), Shimotsuma is the epitome of dull, but she has been forced to live there after her father got on the wrong side of the Yakuza by selling fake Versace. Momoko fantasises about a French Rococo-style existence, full of sleep, sweet foods and lacy apparel. She dreams of the Château de Versailles, and decks herself out in Tokyo’s finest and frilliest haute couture, from the legendary ‘Lolita’ fashion store ‘Baby, The Stars Shine Brightly’.

Momoko is fiercely individual; her motto is “I was born alone, I’ll die alone. So if I can’t live alone, I’d rather be a flea.” She’s also fiercely determined to be pretty – but not to please anyone other than herself. She doesn’t care at all about boys or the other people in Shimotsuma, apart from her eccentric grandmother, and she spends most of her time travelling between Ibaraki and Tokyo for shopping trips. Aspiring to be like the French aristocracy, Momoko feels unsuited to conventional work. She instead uses various unscrupulous schemes to raise the money she needs for Lolita dresses, including selling off her dad’s fake Versace clothes behind his back. One day, when Momoko is lying on her porch, looking pretty, and gazing into the distance, a new ‘Versach’ customer rides up on a motorbike and shakes her out of her hazy Rococo reverie.

Ichiko (Tsuchiya) is a hard-talking, head-butting, dirty clothes-wearing, always-spitting, member of an all-girl ‘Yankee/Bosozoku’ motorcycle gang. In a city, girls from such opposed fashion worlds would rarely socialise. But in their small town world where everyone else buys clothes from the same store, these two girls are pushed together by their unique appearance and individual spirit. They slowly become strong friends, although Momoko does receive one or two head butts from Ichiko along the way.

Kamikaze Girls’ basic premise ‘two kids from different tribes unite and come-of-age together’ is hardly unique – particularly in recent Japanese cinema. But, nonetheless, it is an extremely unusual film; both brilliantly funny and extremely surreal. Director Tetsuya Nakashima employs an array of filming styles and Tim Burton-esque, candy-coloured hues to make Momoko’s life in Shimotsuma seem far less dull than she considers it to be. His imaginative use of animated sequences, plot-rewinds and MTV-like, fast-cut montages borrows from films like Fight Club and Kill Bill and constantly keeps viewers on their toes. In one memorable moment, Nakashima mixes the film’s narration style and has Momoko turn to the camera and says “Now here’s a cartoon to keep you kids amused” before launching into a manga sequence.

Kamikaze Girls offers the western viewer an interesting glimpse into two of Japan’s oddest fashion scenes. Both the Lolita and Yankee styles were massive in Japan in the early nineties and both can still be seen around certain areas of big cities. However, in these cities now their popularity has somewhat diminished; replaced by Hip-Hop, black culture-influenced fashions. These days it is in the Japanese countryside and small towns that Lolitas and Yankees can most easily be found. The film presents both of these youth tribes – whose adherents consider their clothes as part of their skin – in a lovingly detailed way, useful for the uninformed westerner. But the film isn’t pure homage, the two cultures are compared and criticised throughout and in the end both Momoko and Ichiko themselves begin to challenge their ideals.