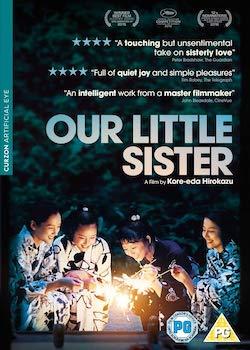

Our Little Sister

Director and scriptwriter: Kore-eda Hirokazu

Based on Umimachi Diary by Yoshida Akimi

Curzon Artificial Eye

DVD, 128 minutes, PG

Review by Susan Meehan

With Our Little Sister Kore-eda has produced another gentle masterpiece – a family drama dealing with death, desertion, vulnerability, responsibility and loss. It is far from harrowing, however, unlike the distressing Nobody Knows (2004) and Like Father Like Son (2013). The tone is altogether lighter, more open, optimistic and with humour. The subject matter, family life, may not be to everyone’s taste, however.

That the four main protagonists are women with strong, weighty roles give it a great touch, and that this in itself seems surprising or unusual, says a lot about the film industry, or at least about the majority of films shown in the UK. It was incredibly gratifying to see these women in such complex and interesting roles.

The principal characters, the Kodas, are three sisters in their twenties who have been living by themselves in a large house in Kamakura for the last fourteen years. Their parents divorced, the father moved out and their mother followed suit within a year. The girls simply got on with their lives, with the eldest, Sachi, taking care of the household and becoming the parent figure, or ‘dorm mother’, at the expense of her childhood.

Having had almost no contact with their parents since being deserted, the sisters decide to travel to their father’s funeral. It is here that they meet Asano Suzu, their half-sister, and herself an orphan, with only a self-absorbed step-mother left to call family. Suzu is self-composed, welcoming, poised and mature beyond her fourteen years, having nursed her father in his last days. She loves the father whom Sachi remembers as merely careless with money and fond of women.

Suzu jumps at the offer of moving in with the Kodas, and Kore-eda shines in his skilful interweaving of the sisters’ family and professional lives and his portrayal of an open, loving and honest sisterhood. There is a strong sense of transience here, as it soon becomes clear that their comfortable, supportive life together can’t last forever. Tensions simmer below the surface as serial dater Yoshino, the easy-going Chizu and the stern Sachi come into conflict. Was Sachi bringing Yuzu into the fold a last vain effort to sustain the family bond?

This is a film in which emotions are discussed openly and issues are confronted. The women have all experienced parental desertion and death and the consequent loss of childhood, but somehow it is Suzu, whose parents had both died by the time she was fourteen, who seems to deal with the loss best. There is little focus on repressed selfless selves, a common Japanese stereotype; only Sachi finds it hard to cast off the responsible persona she has had to develop.

The film’s Japanese scenery is breathtakingly photogenic as the different seasons are skilfully captured over the course of a year and dinky one-carriage trains are shown gliding through the Japanese countryside. Anyone familiar with the Shonan coast will recognise Enoshima and feel nostalgia at shots taken from inside sea-view restaurants. Equally beautiful are the shots of yukata-clad Suzu enjoying the summer fireworks with friends and then contentedly playing with sparklers at home with her sisters.

It is an enchanting, uplifting and moving film which ends with an updated appreciation of their father by the three Koda women. The Kodas’ acting is sublime and Suzu is particularly luminous.