Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts

Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts: From Kishida Ryūsei to Miyazaki Hayao

By Michael Lucken

Translated by Francesca Simkin

Columbia University Press, 2016

ISBN-10: 0231172923

Review by Dominika Mackiewicz

In his book A Japanese Mirror (1984), Ian Buruma, Dutch historian and author of numerous volumes on Japan, describes ‘continuities behind the façade of constant change’ that epitomise so-called Japaneseness. Japanese arts have long been considered as somewhat schizophrenic in their constant attempts to reproduce the West on one hand and their pursuit to portray a ‘national identity’ on the other. Marked by both human and natural disasters, the history of Japan reveals a fascinating need to look into the past with zeal, to rebuild, to reimagine, and to remember.

In his interdisciplinary study Imitation and Creativity in Japanese Arts: From Kishida Ryūsei to Miyazaki Hayao (2016), Michael Lucken attempts to both discern the past in contemporary Japanese art, while also focusing on its innovative characteristics, unpicking and complicating the idea of Japan as a nation of imitators. The book is a survey of Japanese ‘creative imitation’ and the author emphasises throughout the elasticity of mimetism that makes Japanese art so hard to pin down. It explores Kishida Ryūsei’s Portraits of Reiko (1917-1929), Kurosawa Akira’s Ikiru (1952), Araki Nobuyoshi’s Sentimental Journey – Winter (1970-1990) and Miyazaki Hayao’s Spirited Away (2001), and the author’s method is based on initial description, followed by careful historical and theoretical examination. In this way, Lucken avoids fitting works into a predefined theoretical system, basing his analysis on what can actually be seen. These works present an interesting and chronological array that plays with the idea of art’s reflective qualities and forms an enriching dialogue between the old and the new.

The book starts with Kishida Ryūsei’s Portraits of Reiko, a series of twelve depictions of the artist’s daughter, executed one per year around her birthday. The viewer witnesses the striking transformation in the artist’s style and technique, from realistic oil painting à la Holbein, to a chilling ink portrait of Reiko’s demonic face, comprising simple colour on paper in a traditional Japanese style. Through borrowing different methods from other artists but applying them in a highly personalised ‘distorted’ fashion, Kishida creates an uncanny illustration of the passage of time and his own artistic education.

by Kishida Ryūsei

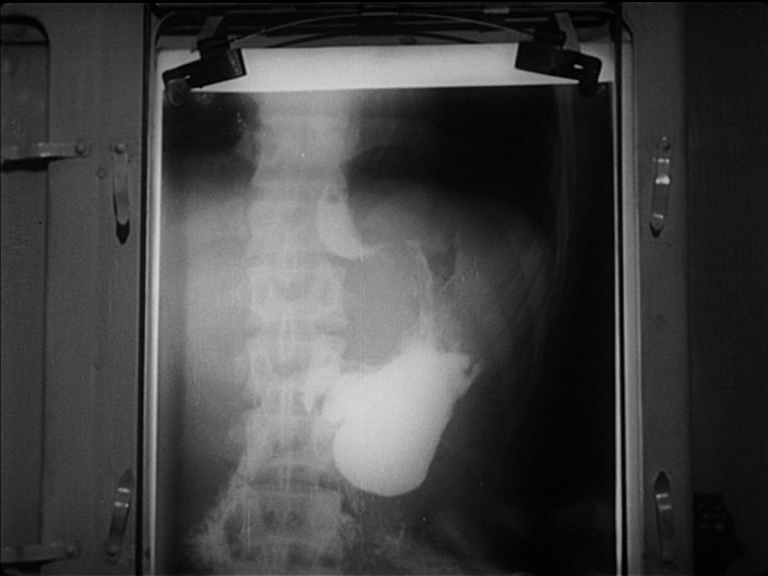

Similarly Kurosawa Akira, famous for his film adaptations of Western literature, tends to direct attention to the nature of the medium. Watanabe, the dying protagonist of Ikiru, a depiction of the last days of a minor Tokyo bureaucrat, wants to make a change, to leave a trace by building a playground in post-war Tokyo’s poorest neighbourhood. While the film bears a resemblance to Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), it is also a highly personal statement from Kurosawa, through which he asks, What is the need of recording? What is the nature of mirroring the world in film? Lucken finds that Kurosawa’s answers are to seek originality in collective creation and to juxtapose ‘the real’ with the ‘aesthetical’; like Watanabe’s impending death, discernible on an X-ray photograph and recorded through the cinematic medium. It is suggested that art is at its best when meeting life.

this cancer’. Still from Kurosawa Akira’s Ikiru

Araki Nobuyoshi is known for his daily routine of taking photos continuously, often of similar subjects and objects. Repetition is a key part of his oeuvre and he uses it in his Sentimental Journey, a series of photographs focusing on Araki’s relationship with his beloved wife Yōko, from their honeymoon to her death in 1990. Lucken focuses here on the significant and unexpected image of Yōko’s hyoid bone being retrieved after cremation. The author’s insightful description highlights how by placing this venerable, yet never photographed, object next to other common ones, such as a Buddhist tablet and Yōko’s portrait, Araki confronts his own fears and society’s dogmas.

In its excellent last chapter, the book takes the reader on a journey through Spirited Away and its recurring visual geographies of verticals, horizontals and ‘adventures of the oblique’. The vertical scenes are echoed in the design of the treacherous bathhouse and reference a city with its all-consuming aspirations and power relations. These are contrasted by horizontal, connective passages filled with tranquillity and restorative powers. Lucken notes the conflicting facets of the high-rise and landscape perspectives, with their underlying social implications, subtly offered by Miyazaki. Out of both, the director distils his own diagonal way, which signifies the unstable, but also the transitional and regenerative. Again, as Lucken proposes, it’s when the art goes askew, that it highlights the importance of mundane recurrence.

Maybe the subtlest of all of Lucken’s interpretations is encapsulated in the outer book sleeve, with the reproduction of Untitled (1959) by Gutai member Sadamasa Motonaga. By using familiar materials and inspired by tarashikomi (a traditional nihonga technique), the painter created a new artistic phenomena in the shape of so-called ‘performance paintings’. Led by the words of Gutai’s leader, Yoshihara Jirō, ‘transformation is nothing other than renewal’, he understood that invention lies in the dissemination and reinterpretation of the past – the repetition that comes from profound appreciation. Following Motonaga’s example, Lucken also harks back to the fathers of re-invention.