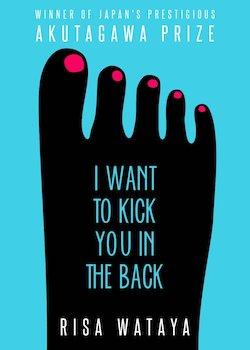

I Want to Kick You in the Back

By Wataya Risa

One Peace Books, 2015

ISBN: 978-1-935548-88-1

Review by Eluned Gramich

‘We were leftovers,’ says Hasegawa Hatsumi of her and her enigmatic friend, Ninagawa Satoshi. ‘Every time our classmates laughed, we grew another year older.’

Written by a nineteen year old student while she was still at university, the bestselling I Want to Kick You in the Back is a slim, deceptively simple tale about teenage life and love. It won Wataya Risa the biannual Akutagawa Prize in 2003, making her the youngest ever recipient of Japan’s most prestigious literary award. Skilfully translated by Julianne Neville, this is the first time Wataya has been made available to an English-speaking readership, and I’m sure it won’t be the last.

That the author was so young when she wrote this novel comes as no surprise. The story follows a young girl, Hatsumi, as she moves into Middle School and struggles to adjust to her new environment. She knows nobody apart from her best friend, who has found a new friendship group that Hatsumi doesn’t approve of. As a result, she spends her lunchtimes on her own, avoiding other people and complaining about her life. A boy in her science class, the quiet Satoshi, also chooses to avoid socialising with his fellow classmates. They become friends and Hatsumi finds out that he is a super fan of the teen idol, Oli-chan. Very soon, Hatsumi gets sucked up into Satoshi’s fantasy world, his lust and obsession for an unattainable celebrity girl who pretends to be younger than she is. Hatsumi puts it this way: ‘She (Oli-chan) was an intrinsically young person, a person good at being young. And then there was me, actually young but terrible at it.’ Hatsumi’s tone is intimate, natural and entirely believable as Wataya succeeds in capturing the mixture of insecurity, defensiveness and put-on bluster of a thirteen year old.

The type of the ‘creepy’ super-fan is not new to Japan and perhaps partly explains why the novel did so well with readers there. It taps into the contemporary “fandom” phenomenon, famously typified by the legions of male fans who follow the teen pop group AKB48. In Japan, unlike in the UK, this is the terrain of (usually single) men. Wataya approaches this subculture, not by trying to speak from a male standpoint, but by using Hatsumi to voice the confusion and worries that readers might share. Like many women, she fails to understand why Satoshi is more interested in a distant celebrity model than in the living, breathing girl sitting beside him.

The obsession for teen idols embodies so much of what it means to be young: the desire for a role model, the need for guidance and instruction. It’s a place where you can put all your feelings: desire, love, loneliness, lust. More than anything the novel is about sexual awakening. This is somewhat hidden at first by the misleadingly innocent and child-like language and setting. Far from being part of a teenage tantrum, Hatsumi’s desire to kick Satoshi in the back is bound up with the intensity of his sexual fixation on Oli-chan. It unleashes her ‘violent desires… inspired by a feeling stronger than mere love or affection.’ At one point, Hatsumi discovers something shocking, stomach-churning, locked away in Satoshi’s ‘fan’ box: this discovery hails the start of a new kind of longing in her. Even her female friendships begin to glow with sexual tension, because for her, a girl on the verge of becoming a woman, everything is lit up with a new energy she barely understands.

This short novel is the sort of book you can read in one sitting: the sort of book which sends you into another world, another person’s life, for however brief a time, and does not let you go afterwards. The first person voice is seductive through its honesty and strength. In the intersection of violence, obsession, and sex, Wataya has caught the whirring-headed confusion of two teenagers who have a lot yet to learn.