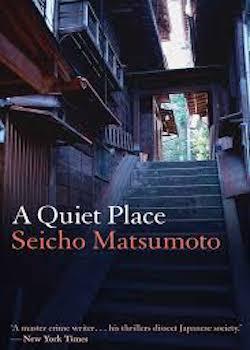

A Quiet Place

By Matsumoto Seicho

Translated by Louise Heal Kawai

Bitter Lemon Press, 2016

ISBN-10: 1908524634

Review by Harry Martin

Only a handful of Matsumoto Seicho’s works have yet made it into English, and yet fledgling entrants to the world of Japanese crime fiction will soon come to realise that prior to discovering his prolific output they have been paddling only within the smaller tributaries of the genre, oblivious to this great river which flows with powerful currents of national sentiment and a cult following. I have been shamed by Japanese friends and colleagues for allowing this revered author to remain so long outside my consciousness. A Quiet Place (Kikanakatta Basho) was the last of Matsumoto’s novels to be published and at 228 pages is by no means a lengthy or arduous undertaking.

The story begins with a hardworking and dedicated government official receiving the news of his wife’s untimely death while he is away on a business trip in Kobe. This is followed by the proceeding twists and turns of the grieving husband’s own investigation and pursuit of the truth. Spurred on largely by the protagonist’s paranoid and obsessive nature, the reader is led through a somewhat formulaic process of conspiracy, intrigue and discovery, typical of the crime fiction genre; a cast of mysterious and stimulating characters and cryptic undertones make for an enjoyable journey.

However, what I found interesting about Matsumoto’s writing is that he does not focus the attention of the narrative on police or judicial investigatory procedures. Rather the narrative centres on the wider context of Japanese society and social psychology, with Matsumoto scrutinising social norms and day-to-day interactions and relationships in routine life.

The story provides an insight into the layers of duty and social obligation (giri) found in many aspects of Japanese society, from spousal relationships to interactions with corporate and government organisations. Matsumoto presents a bountiful array of examples amplifying the complexities and intricacies of this social phenomenon. For example, at the opening of the story the bereaved husband, moments after hearing of his wife’s death, seems to concern himself only with resolving the embarrassment and inconvenience caused to his superiors. This extreme example of giri really opened my eyes to the sometimes crippling nature of this sense of obligation.

The theme of giri plays a recurring and important function in the writing, dominating multiple interactions among the characters and essentially driving the story forward at every turn. The often extreme and hyperbolic nature of the main character’s moral conflicts are, at times, comical and make me feel a possibly nihilistic scepticism at play in Matsumoto’s critique of social norms.

Overall this is a compelling crime thriller with a captivating storyline and interesting characters, providing an enjoyable and effortless read, offering an insight into Japanese social-politics. I feel this book has a lot to offer all crime fiction aficionados, but for me it opened a door into a world of revered Japanese fiction written by an extraordinary author and personality, which should be on the radar of any fan of Japanese literature.