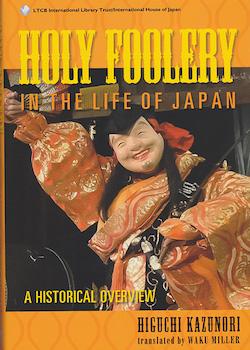

Holy Foolery in the Life of Japan: A Historical Overview

By Higuchi Kazunori

Translated by Waku Miller

LTCB International Library Trust/International House of Japan, 2015

ISBN-13: 978-4-924971-40-0

Review by Hugh Cortazzi

‘Before the modern era, people in Japan and in other nations tolerated and even welcomed foolery in their heroes. Modernization, at least in Japan, ushered in a preoccupation in schools and in the workplace with seriousness and diligence. Japanese society lost its tolerance for silliness. People came to regard foolery as socially useless, as mere frivolity’. So declares the author of this thought-provoking analysis of the role of laughter in Japan.

Foreigners who only meet a few officials and business executives, in whom the importance of serious (majime) attitudes has been inculcated in school and university, foster the idea that the Japanese have no sense of humour. This impression is reinforced by the lack of a simple Japanese term for sense of humour other than ‘umoru no sensu’. (Once when years ago I was giving a speech in Sapporo and referring in Japanese to this problem one old gentleman misheard me and asked what I meant by ‘umoru no senso’, senso meaning war!).

In fact as Higuchi points out laughter and fun have played a significant role in Japanese mythology and folklore since the earliest times. The kanji for laughter, 笑い (warai), apparently ‘evolved from an ideographic representation of a shrine maiden extending her arms upward while dancing’. He notes that the sun goddess Amaterasu-omikami who had hidden herself in a cave because of havoc caused by her brother Susa-no-o was only enticed to emerge when Ame-no-uzume caused peals of laughter by dancing wildly tearing off her clothes and exposing her breasts ‘and even her genitalia’.

Foolery and laughter, as Higuchi points out, have been important elements in Shinto mythology ever since. He quotes many examples from Japanese folklore drawing on the writings of scholars such as Yanagita Kunio and the eccentric Minakata Kumagusu, who was the subject of a biographical portrait by Carmen Blacker (Britain and Japan; Biographical Portraits, volume I, ed. Ian Nish, Japan Library, 1994).

In Japan as in Europe ‘great’ men needed to be kept amused and had their ‘fools’ or jesters. One of the most famous of these was Sorori Shinzaemon who served the ‘ruthless warlord’ Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598). Hideyoshi had an ‘inferiority complex about his appearance’ and confessed to Shinzaemon that he thought he looked like a monkey. Shinzaemon responded ‘No. Sire. So in awe of your greatness are the monkeys that they distort their faces to look like your Highness’s’. Shinzaemon escaped punishment.

Japanese serious and stately noh dramas were lightened by short comic playlets or kyōgen. These often depicted ‘scams and hoaxes’ and servants getting their own back on their masters. In Japan as in other cultures laughter is often roused by lampooning the pompous and the overbearing.

Unfortunately humour of this kind can also be cruel. It is easy to make a fool of the ‘village idiot’ who may have been born mentally deficient or crippled. But laughter can also, as Higuchi points out, play a role in lightening the horrific effects of natural disasters, to which Japan is sadly so prone. Laughter can be seen in such circumstances ‘as an expression of relief and as a sign of safety’.

Higuchi’s book is not and does not claim to be a history of Japanese humour. He does include Hokusai and his manga, but it does not cover senryu (haiku-length witty verses) or comic novels of the Edo period. Nor does it discuss modern comic manga and strip cartoons. And there is nothing about modern writers of comic stories such as Genji Keita whose ‘salaryman’ stories I used to translate. But a book covering all these aspects of Japanese humour would be a hefty tome.

I feared when I began reading Higuchi’s book that he might put too much effort into analysing the psychology of laughter and defining the meaning of humour in ways that deaden any sense of fun. But while there were interesting lessons in folklore, religion and history in his book I realised that he did not want his readers to approach his subject in too majime a way. Many of his examples are amusing as well as informative.