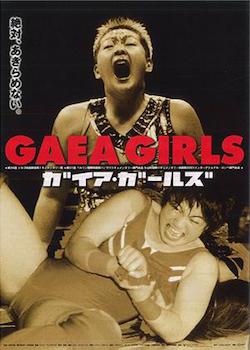

Gaea Girls

Directed by Kim Longinotto and Jano Williams

2000

Available on DVD from 25 January 2010 as double release: Gaea Girls/Shinjuku Boys

Review by George Barker

In a 2016 interview for The Japan Times, ‘Big Bang’ Nicole reflects on why she moved from America to Tokyo in order to pursue her lifelong career ambition of become a professional wrestler. She establishes not only that Japan is still considered today as a mecca of (female) wrestling, but furthermore likens her training regimes to those she imagines were undertaken by Spartans. Interesting for this re-view of Gaea Girls, she also draws a distinction between audience perceptions of the sport in America and Japan. ‘Kayfabe’ – an industry specialist term used to describe the portrayal of choreographed fights and staged storylines by the wrestling industry as real events – is a dwindling phenomena in the WWE dominated world of the West. However in Japan, Nicole argues that kayfabe is “still very much alive. So for the Japanese fans it’s still very much real, and for myself it’s very much real”.

In Kim Longinotto’s observational documentary the line between reality and staging in the profession of female wrestling (joshi puroresu) is addressed with ambiguity. On the one hand, the training regimes documented over the three months that Longinotto spent filming depict the mental humiliation and physical degradation of the trainee Gaea Girls in a way that is alarmingly real. For example when Takeuchi – an upcoming Gaea Girl whose training trajectory is the narrative core of the film – is filmed in an early training spar, she receives a drop-kick to the face and stands bleeding heavily whilst awaiting feedback. In the next scene we find out she subsequently had to receive stitches to the face as a result of this bout.

On the other hand, much of the movement in this training spar scene is noticeably choreographed. Similar are all of the numerous scenes showing public matches. Although Longinotto has obtained frank and honest access to the regimes of the Gaea Girls, underlying questions of the authenticity of joshi puroresu as it existed at the turn of the millennium remain unexposed. Therefore to an extent, the brutality of what is displayed in Gaea Girls stands in conflict with the trickery of choreography at the heart of entertainment wrestling. In a film where silence predominates, lingering questions about the truth of what is being shown are founded by this documentaries lack of interrogation into kayfabe as an integral component of professional entertainment wrestling.

Propelling the film forward instead is the documentation of physical exertion by these female subjects. While the repeated aural motif of ‘ichi, ni san’ (one, two, three) affirms the repetitive nature of their training, images of the body under strain and stress dominates Gaea Girls; perhaps to the extent that exertion overtakes contextual explanation. Yet, in the framing and editing of these physical scenes, Longinotto carefully and continually draws out visual metaphors that place this exertion in context. An example of this is in the final fight scene when we see a conservative mother figure in the audience wince slightly at the sight of seeing Takeuchi under such enormous physical pressure.

Whether or not this is her own mother is only implied by context. Likely it is not because we do not learn anything about the familial relationships of the Gaea Girls within the film, which rarely strays outside of exposition directly involving the training group. However Longinotto suggests through this gaze how these young female wrestlers may be situated as radical figures within Japanese society. As Takeuchi discerns early on, she became a Gaea Girl in order “to stand out”, assumably from other more prototypical delicate constitutions of femininity in Japan. In the scene before this brief interview, we see Nagayo Chigusa, the head trainer, flick through male hairstyle magazines whilst getting her head shaven. In conjunction, these scenes suggest that at the heart of the Gaea Girls is a tough and altogether physical redefinition of Japanese female subjectivity, which is framed here through extreme bodily exertion.

The film also offers great insights into the hierarchical dimensions of teacher student relations that exist in Japan. Chigusa asserts early on that she sees the trainee Gaea Girls as her own children, but the relationships between Chigusa and the other girls don’t feel familial. Instead, their dynamic appears to offer a hyper-emphasised portrait of how respect of a sensei (master) figure operates in Japanese society. Even when – under obvious strenuous conditions – girls leave the Gaea training regime, they are subject to and abject themselves to extreme scorn from their teachers with obedience. In these moments, Gaea Girls depicts an extremity of hierarchical respect systems that seem altogether nationally specific and traditional. This is despite the Gaea Girls’ assumed outsider or alternative role within Japanese society at large. The extraordinary choices of these women are therefore subsumed under traditional regimes, provoking whether or not the Gaea Girls constitute an alternative lifestyle and redefinition of femininity, or are more akin with conservative and at times aggressively submissive teacher-student relationship dynamics.

When revisiting Gaea Girls as part of a screening series organized in co-operation with The Japan Society and the Royal Anthropological Institute, it became apparent that despite professional wrestling’s obvious associations with choreography and escapist populist entertainment, the violent training regimes that take place in Japan can pertain to altogether serious and unstaged social issues. Although Gaea Japan disbanded in 2005, Chigusa Nagayo continues today to train women and men under a new ‘promotion’ called Marvelous. By secluding any authorial voice and focusing on physical action, Gaea Girls certainly provokes more questions than it answers. However, these provocations remain relevant today as an important snapshot into violent practices that are not often made public but are still very much alive.

Gaea Girls Film Screening and Q&A on Tuesday 24 January 2017. More information / Book online