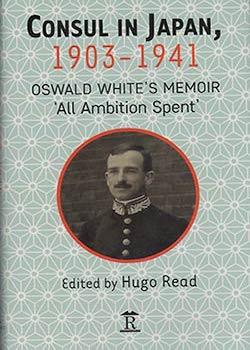

Consul in Japan, 1903-1941. Oswald White’s Memoir ‘All Ambition Spent’

Edited by Hugo Read

Renaissance Books, 2017

ISBN-13: 978-1898823643

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Readers should not be put off by the tittle of this book. ‘All ambition spent’ suggests a disappointed man and a dull life in a far off corner of the globe. In fact the book contains much of interest to the historian and to anyone concerned with the international relations of Japan in the first half of the twentieth century.

Oswald White first went to Japan in 1903 as a ‘student interpreter’ in the British Japan Consular Service. In Japan he served in Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagasaki and Osaka. He had two stints in Korea. His final postings were as Consul-General in Mukden and at Tientsin ending in 1941. From these posts he observed the evolution of Japanese foreign and economic policy.

Those of us who have experienced the postwar scene in Japan and have studied Japanese in different circumstances may be amused by some of his comments on language study, the work of consular officers in his era and their role in relation to trade.

His final chapter on Anglo-Japanese relations, which was written in 1941 while he was on leave in Canada, is well worth reading carefully. It contains many points, which are still relevant today.

He had retained his liking for Japanese people, but had no illusions about Japanese motives and behavior in East Asia. He noted that ‘Japan never showed any particular consideration for British interests. It was significant that wherever she gained control, British trade faded out of the picture’. (p. 200) The Japanese were, he thought, ‘very self-centered’ and ‘do not readily see the other man’s point of view’. ‘When the time comes that another nation blocks what he considers his natural expansion then to him it is the other nation that is the aggressor!’

He is, however, just as scathing about British policies in the Far East. In the decade from 1930 to 1940 Great Britain had fallen between two stools. ‘Its tactics were either too strong or not strong enough. It scolded Japan in season and out of season for its doings in China but it merely succeeded in infuriating her’.

White drew attention to Austen Chamberlain’s comment that the British ‘decide the practical questions of daily life by instinct rather than by any careful process of reasoning’. He thought that the British tendency to inspiration at the critical moment had been ‘apt to result in British officials at different posts pulling in different ways…with disastrous results’. Here he was no doubt thinking of the open disagreements in the 1930s between the British missions in Peking and Tokyo.

In a swipe at appeasement he declared that ‘Our old doctrine of the balance of power, our opportunism, our tendency to range ourselves in recent years on the side of lost causes and then watch them go under all give the impression to outsiders that we are unprincipled’. This approach and our attempts at playing one country off against another had led, he felt, to Britain being seen as ‘old and cunning’ (in other words as ‘perfidious Albion’).

He was critical too about the lack of foresight in the formulation of British policy towards Japan. He noted that in our desire to maintain our established rights, we had ‘no definite plans, no strategy and, as a result, the tactics we have devised at the eleventh hour have not been wisely chosen’. In his view ‘we carried on as though we were still living in the good old days when a protest backed with a threat of action could carry the day’. But we had neither the will nor the means to take effective action. Our threats were seen as empty and as ’we climbed down all along the line’ our bluff was called.

His conclusion that there was ‘some truth in the criticism that we never forget and we never learn’ sadly resonates today.