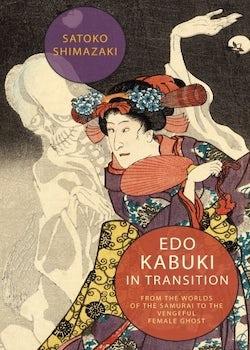

Edo Kabuki in Transition: From the Worlds of the Samurai to the Vengeful Female Ghost

By Shimazaki Satoko

Columbia University Press, 2015

ISBN-13: 978-0231172264

Review by Trevor Skingle

Quite obviously a long time in the writing, Assistant Professor of Japanese Literature and Theatre at the University of Southern California, Shimazaki Satoko’s seminal work focuses on the developments and changes in kabuki since the 1825 premiere of Tsuruya Nanboku IV’s play Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan (The Ghost Stories at Yotsuya on the Tokaido). She uses that play and its premiere as a starting point and, contrary to what is said, as a pivotal point in the history of Kabuki. Importantly though the author does provide an enlightening contextual exegesis as to the important difference between the two in the development of kabuki plays and their performance.

An early assertion that generally used English translations of the titles of plays would be used is contradicted by the author’s translation of the play’s title into English as ‘The Eastern Seaboard Highway Ghost Stories at Yotsuya’. This departs somewhat from the internationally used English title ‘The Ghost Story of Yotsuya’, though this is used subsequently throughout the rest of the book. The reason why the first translation is initially used is not explained and, though this may seem a petty point to highlight in light of the academic rigour of the book, an explanation might have been helpful.

Further on in the Introduction the author proposes her two main issues that inform the rest of the book. That kabuki can be perceived in two ways depending on whether the viewpoint is that of historical Edo or modern Japan. The first is that kabuki performances were part of a traditional and community based interactive dynamic and creative social process (dento), the ‘ephemera’ of which have since been overshadowed and replaced by the modern. This second one is a more static interpretation which revolves around the text bound handing on and use of scripts as they are (densho). As a result of this, kabuki ‘ephemera’ have generally been lost to the world of modern kabuki. This isn’t very controversial, and it’s a theory that’s not particularly borne out by modern evidence of the continued interaction between theatre and audience, including ad hoc changes to the scripts witnessed during around sixty performances over a period of thirty years, and the interaction between fans and actors, and fans and the actors’ staff managers or banto san, albeit these days no doubt to a lesser degree.

She also argues that the historical samurai based worlds, or sekai, that formed the basis for kabuki in the past, were gradually replaced around the time of Nanboku by the notion of the female ghost and its associations with the intensely emotional feminine states of jealousy, resentment and desire. The main part of the book expands on and elucidates the theories expounded in the Introduction occasionally wandering again into the over romanticised. For instance it is also suggested that the communal theatre space was a liminal threshold, a space linked to the realm of other and that this was suggested by the name of the space under the stage and hanamichi walkway through the audience (naraku meaning hell). This idea comes across as something of a romantic overstatement. Quite simply put, in the way of Japanese sharé or word puns, the reason for this was because it was so dark and dingy it reminded people of the underworld.

The issue of liminality of theatre space is again brought up in regard to the theatres use of and proximity to riverbanks as a utopian symbol. Yet no mention is made of the other extreme, the generally accepted historical use of the term kawara-kojiki (or river bank beggars) to refer pejoratively to Edo era kabuki actors, and riverbanks as places of implicitly dubious entertainment.

The list of subject areas covered in the book is extensive and these are just a few of the early examples. A critique of the proposed theories would fill enough space to make another book, but then perhaps the intention is for the narrative to be provocative. Suffice to say that this book does not make easy reading, its academic distinctiveness leaping from the page. Early on it wanders into academic jargon when the reader would do well to keep a dictionary to hand, ironically not for the Japanese terms but for the thesis style English. Many associations in the book are over romanticised in a predominantly academic way, theories squeezed to fit the author’s ideas, which can occasionally be quite frustrating. The book works best when it relates historical facts to support the arguments about the development of kabuki from the twin perspectives highlighted previously; dento and densho. It works least when it wanders off into academic text-babble musings. There is an extremely useful and informative notes section which for a book such as this is always advantageous.

On the whole, the book is a fascinating mix of the informative and is scattered throughout with some obscure historical eyebrow raising facts, and the author’s weighty theoretical narrative, a daunting adventure for whoever dares to enter, and a steep learning curve for the uninitiated. Not for the general reader, which is ironic considering that kabuki was created for the plebeian sections of Japanese society and at nearly £50 a considered purchase rather than an impulse buy.