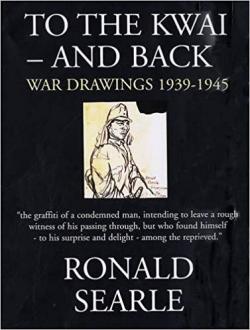

To The Kwai - And Back; War Drawings 1939-1945

By Ronald Searle

Souvenir Press, April 2006

ISBN 0285637452

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Ronald Searle, the creator of the girls of St Trinians and one of the ablest and most famous British cartoonists, was a prisoner of war of the Japanese from February 1942 to August 1945. With determination and courage he managed to keep a record in drawings of his years of suffering as a prisoner in Singapore and on the Burma-Siam Railway. He describes the sketches in this book as "the graffiti of a condemned man, intending to leave a rough witness of his passing through, but who found himself - to his surprise and delight - among the reprieved." These drawings selected from the originals which he succeeded in bringing home are now part of the collection of the Imperial War Museum in London. They are harrowing and moving.

Ronald Searle's narrative is spare and restrained. The story begins with his joining the army as a volunteer in April 1939 as he realised that war with Nazi Germany was inevitable. He was a sapper in the engineers and remained a private soldier to the end. His unit was sent to Singapore where he arrived on 13 January 1942. They were untrained and unequipped for jungle warfare. His unit was ordered forward to destroy everything in front of the advancing Japanese forces. It was, he said, "a scorched arse policy" and the Japanese "moved forward to chop into small pieces all the wounded that had to be left behind." Singapore which had suffered from "years of inept, incoherent and chaotic political and military mismanagement" by the British lay at their mercy but the Japanese forces showed no mercy. "It is estimated that 20,000 Chinese alone were shot or beheaded during the first few days after capitulation." Searle drew two gruesome sketches of severed heads on poles and on shelves. (See drawings on pages 66 and 67).

"The forced marches continued through the nights and memories of them have become a compression of smells and feelings; plodding along a glutinous track thick with pitfalls, faces and bodies swollen and stinging from insect bites and cuts from overhanging branches that whipped back at us." If at roll call the total was short "it meant a thrashing for someone with the ubiquitous bamboo stick - and being beaten with bamboo is like being beaten with an iron bar." Their "working methods were barely out of the stone age " and their conditions were made worse by the flies, the mosquitoes, the lice and the bedbugs and the very inadequate rations.

"Some of our overseers had an extremely primitive sense of humour. During the noon break on the cuttings, they would frequently relieve their boredom by calling us into line before we had barely gobbled down our rice, to watch the torture of one of us picked at random. The unlucky one might be made to hold a heavy rock above his head in the full sun, with a sharpened bamboo stick propped against his back. If he wavered, which he inevitably did, the bamboo spear pierced his skin" (see drawing on page 114).

Eventually he was returned to Singapore to the horrifically overcrowded Changi jail to work on levelling the ground for a military base or to work in the docks. He managed to escape the attentions of Kempeitai who had their own prison in Outram Road, but he was always afraid that his sketches would be found. Fortunately for him the Japanese were very frightened of cholera and cholera sufferers helped to hide his drawings.

Some among the Japanese guards did show a little kindness. One named Ikeda spotting Searle sketching showed him photographs of his family and asked for a sketch of himself to send to his mother, There was also a Captain Takahashi, who summoned Searle and three other sappers to work at his house, drew a mother and child in Searle's sketchbook and confessed that he too was an artist who had been studying in Paris when he "was called home to this - ah - to serve…" He then gave Searle a handful of coloured pencils and wax crayons. Searle would like to have made contact with him but had no success.

On 15 August 1945 the Japanese authorities "announced that although Nippon had agreed to unconditional surrender, Field Marshal Count Terauchi, Commander-in-Chief of the Southern Army, did not associate himself with it and intended to fight on. What we did not know then was that a plan existed at Count Terauchi's Saigon headquarters to execute all prisoners in case of invasion." British Forces were indeed massing for an attack on Malaya, the so-called operation "zipper." Fortunately for all of us sense prevailed, but it was not until 28 September 1945 that Ronald Searle finally boarded a ship for home.

There can be no doubting Searle's story. His drawings are a vivid testimony of the truth and of the suffering of so many. I wish that Japanese historical revisionists and Japanese nationalists would read this book. They might then begin to understand why we object to Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi and Foreign Minister Taro Aso paying their respects at the Yasukuni shrine where the Yushukan museum glorifies war and the Japanese military. They should be remembering all those who died and suffered during the war including the civilian dead in Singapore and, of course, in Japan itself.