Sennan Asbestos Disaster

Directed by Hara Kazuo

2017

Review by Roger Macy

Hara Kazuo is probably the best-known director of Japanese documentaries in the West, with a number of his films available on DVD, including his 1987 Yuki, yukite shingun, retitled in English, The Emperor’s Naked Army Marches On.

After years of immersion with his subjects, in 2017 Hara completed a new documentary on an epic fight of the bottom with the top of Japan, The Sennan Asbestos Disaster. Prior to its release in Japan in March 2018, this film has already won the audience awards at both the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival and Tokyo FilmEx, following its award of the ‘Best Asian documentary’ at BIFF in Busan.

Sennan is an industrial area of Osaka, on the southern fringe of the city where Japan’s asbestos industries were concentrated. To anyone above a certain age in the West, ‘asbestos’ is just a historic material, sometimes discovered when renovating or demolishing old structures, which requires strict precautions to prevent inhalation of the carcinogenic fibres. Its use in construction, or any other purpose, has long been banned.

Not so, in Japan, where asbestos continued to be manufactured until around 2006, when the government finally banned its use, some 40 years after other major economies, and about sixty years after its health hazards were first identified.

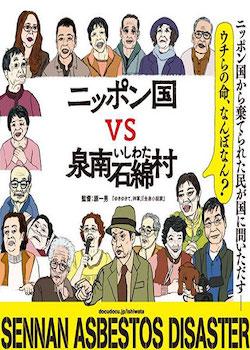

Hara’s long film gives the briefest of briefings on that historical background before spending nearly all of its four hours following a group of ex-workers of the area during their eight-year struggle to get some compensation from the government for their health problems. Indeed, the Japanese title of the film is ‘Nippon koku vs. Sennan ishiwata mura’ – ‘The Japanese state versus the asbestos village of Sennan’ (the city of Sennan where most of the claimants came from). Most publicity on the film follows the briefing of Hara’s company in saying that the film documents the court battle. It doesn’t. Hara does not even glance at the legal arguments and procedures. Although not able to film in court, he could have re-enacted scenes or given an account of some of the arguments but he is not interested in these points, which were, after all, decided long ago – at least by the 1970s, in other legal domains [1].

What Hara documents is the final eight years of these people’s campaign to get compensation. Their unimpeachable argument was that, for decades, the Japanese government chose to encourage the continuance of an industry that was considered to be deadly by competent experts and authorities elsewhere. The legal landscape in the West is that there has been no resistance to the facts of the damage, with occasional resorts to the courts to determine leading cases that test and quantify precise liabilities. But in Japan, the government, years after the medico-legal facts were determined, fought a tenacious battle to deny liability whatsoever. In a legal domain less deferential to power, the Japanese government might reasonably have been ruled a vexatious litigant for doggedly arguing the unarguable and been curtailed by abbreviated procedures; but it was allowed to appeal, at a snail’s pace, to every possible court, until there were none left in 2014.

Hara could, and should, have interrogated that denial. In Western countries, it has been the insurance companies who have had to foot the bill, as they preserve their liability, even after the closure of their clients who paid their premiums. Nothing in Hara’s four-hour documentary even touches on their absence from providing compensation in an economy with a highly advanced insurance industry. Nor does it explain the dates that eventually limited the government’s liability to a period roughly from 1973 to 2006. Presumably, the audience at the Foreign Press Club of Japan conjectured, the earlier cut-off was when the government could no longer claim ignorance of the effects of their policies. I can only assume that the absence of insurance companies from the fight was a result of a second failure by government to enforce employee liability insurance. After all, an insurance company, in the business of assessing risk, needs to be even more aware than the government of the health hazards, and its premiums would have rendered the industry uneconomic much earlier.

None of this is even hinted at in Hara’s documentary, which focuses, without blinking, on the campaign of the claimants. This should come as no surprise to anyone who knows anything of Hara’s work. Relatively little is spoken to the camera or to Hara, we mostly observe members of the group in conversation or demonstrating their grievance. The significant change in his latest film is that it’s a struggle of a group, rather than an individual. There is an interesting discussion where some members try and highlight the preponderance of minorities in their midst, only to be resisted those of Korean descent, who don’t want to be defined as such.

One member, however, does stand out, often literally, although he is scrupulous in his commitment to the collective. The founder of the Citizens’ Group for Sennan Asbestos Damage, Yuoka Kazuyoshi, was introduced as the ex-manager of one of the factories which was owned by his family. That crucial double identity of the most outspoken of the claimants is mentioned at the beginning before we realize how repeatedly he will put himself in the line of fire; but it is not examined further, nor are we reminded of this during the four hours, the better to have pondered his motivation.

Just one example of Yuoka’s actions must suffice. The group have waited but never rested for years, as they stand outside various courthouses for the inevitable victory, followed by another long-drawn appeal. This time, they are off to Tokyo for a press conference to publicise their objection to another government appeal. But Yuoka suggests to the group that they attempt a direct appeal at the prime minister’s residence. He eventually persuades the group that they cannot ask the permission of their lawyers as they couldn’t say ‘yes’. That struck me as a very atypical Japanese insight. Yuoka is unflinching as he takes on waves of gatekeepers at the prime minister’s residence in fruitless application.

Far more bizarre is a later round where the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare admit the group into their building for them to ask for the appeal to the High Court to be waived. The Ministry allow this meeting to be adjourned, daily, readmitting them – along with Hara’s camera – for weeks of stonewalling where an endless supply of the most junior officials merely state that they have no authority to disclose if any decision has been taken. We are left to guess why a ministry would prolong themselves being depicted so poorly on camera. I presume that no news-teams were admitted and Hara was regarded as too committed to reach a wide audience. And, if the object of appeal is to delay justice, then spending a few more weeks failing to explain one’s actions does not undermine one’s objective. Incidentally, this government department is consistently abbreviated in the subtitles as ‘Health’ ministry but is the government’s non-regulation of industry and labour that was lacking.

Eventually, the appeal to the Supreme Court is lodged by the government and, more years down the line, it loses. So, if the government lost the final battle, did they lose the war? Hardly. Hara has taken us on an emotional journey where we have formed a relationship with the claimants over many years, seeing many of them die. But it seems that the government have not been ruled liable for all asbestos workers after 1973, but only those who were foolhardy enough to devote years of their life to fighting their government, and then only those that survived to receive the compensation. One claimant, in particular, survived the entire legal process only to die three days before the titular visit of the Minister of Labour.

But the show must go on. Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare: Shiozaki Yasuhisa came down to Sennan to make formal apology. Whilst the news media got slots for their cameras as Shiozaki made his performance to various claimants, Hara evidently drew the straw for the minister’s apology to the late Machimoto Sachiko. Shiozaki duly performed the apology to Machimoto-san’s corpse with exquisite manners. I hope that my reviews continue to eschew any ‘only in Japan’ gloss but, on this occasion I find it hard to resist. Those manners are seen to win over the poor claimants of ‘the asbestos village’, who are heard having nothing but gratitude to express for the minister who took eight years – and all the courts in the land – to apologise. I had my reservations about Hara’s general depiction – removing the legal arguments had conveyed a bi-polar, feudal relationship but, if even the very few who fought and won have such deferential gratitude then my objections must be dismissed.

Hara avoids any suggestion of conspiracy and never speculates as to the locus of the mind of such government resistance to its responsibilities. For my part, the only way I can understand it as rational behaviour is if the government is aware of much wider liabilities for similar industrial policies in the period of high growth. Another kind of documentary would have homed in on whose Departmental budget these liabilities actually fall. Since they fall outside annual allocations, they surely are taken up by the Ministry of Finance. The formal apology of a mere minister of health or labour may just be a bishop’s sacrifice when available pawns have run out. The stakes for the government had, of course, increased by trillions of yen during the course of their resistance, as by now they are also disputing through the courts their liability for inadequate regulation of the nuclear power industry.

The film was not quite over. We saw the formal meeting of the Group where they decided to redistribute their compensation so as to recompense even those who had lost entirely due to the 1973 cut-off. It struck me that it would have only taken one member to object for that plan to have unravelled. It was a sweet moment of collective generosity – in painful contrast to that of some other claimant groups – from a community for whom we had formed a rich bond during the four hours of Hara’s off-centred but inspired documentary.

[1] For anyone who needs more information on the legal landscape of state liability for industrial diseases in Japan, a recent review paper by Kawamura Hiroki, 2018, has been translated from the German, although this also overlooks the absence of insurance companies. ‘The relation between law and technology in Japan: liability for technology-related mass damage in the cases of Minamata disease, asbestos, and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster’, Hiroki Kawamura, Contemporary Japan 30:1, pages 3-27.