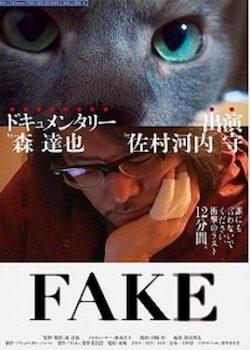

Fake

Directed by Mori Tatsuya

Showing at Aperture: Asia and Pacific Film Festival

Cinema Museum

Saturday 30 June 2018

Review by Roger Macy

There is a long tradition by documentary filmmakers, not just in Japan, of bringing the underdogs to the centre. Mori Tatsuya, however, has made a speciality of going further. He has given voice to figures of hate and derision in Japanese society.

The controversial positions he has staked out in Japanese discourse and in his books are numerous but his international position rests primarily on two films on the Aum sect – A, 1997, and A2, 2001. Japanese readers will not need reminding that it was some members of the Aum sect who perpetrated the sarin gas attack on the Tokyo metro. As far as I recall, Mori gave no voice to the violent in A, (if A2 has ever reached these shores, I didn’t find it) but in his latest film Fake he has found an entirely non-violent subject. Nevertheless, Samuragochi Mamoru is a figure buried in infamy in the Japanese media.

This review will go into more detail into certain parts of the film than I usually reveal for reasons that I hope will become apparent. But the substantial time devoted to the two people on whom the camera dwells can be left for the viewer to appreciate.

The brief opening of Fake gives enough to remind Japanese viewers of the story so far, but I think a little more is needed with those not familiar with it. Samuragochi became a familiar name as the composer of music in a romantic style (a style non-musicians often call “classical”). But what really got him prominence and a continuous feed of media stories – for eighteen years – was that he was deaf. Except, as Mori’s introduction says, he was none of this. As rumours started to rise, in 2014, a college lecturer emerged to confess that he had composed the music and that, what is more, Samuragochi had normal hearing. The said lecturer, or soon-to-be ex-lecturer, Niigaki Takashi, has subsequently become a media personality in his own right. Samuragochi, in contrast, after one disastrous press conference, went into purdah, and has remained the butt of chat-show jokes. I can’t help feeling that this ugly turn in the popular media, has much to do with a public trying to purge itself, with a feeling of being had – of being cheated upon. For the media, and its faithful public, had embraced the story with enthusiasm. Samuragochi was “the modern-day Beethoven”. Samuragochi had even provided the foundation myth for this religion. As he lost his hearing, he recounted in his autobiography, he had an existential crisis until he realized that he could write down Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata from memory, and could find it the same on the page as the original – his composing tools were intact. Except that the real Samuragochi can still neither read nor write music.

I should state here, before I fall into fakery, that I have not read a word of Samuragochi, but am dependent for information on a 7,000 word article by Chris Beam in New Republic. Beam appears in Mori’s documentary and it his Japanese-speaking collaborator who elicits the crucial confession of Samuragochi’s illiteracy.

Mori’s own interest in the pariahs of society is driven by at least two strong tenets. One is his distaste of the unfortunate way people tend to define themselves with reference to an out-group. The second is his abhorrence about the way the media round on victims.

So, it is not so surprising that Mori would seek out Samuragochi, and that only Mori would get accepted. That, however, does not guarantee him any content for his film; especially as Samuragochi has little contact with the outside world, and Mori does not press home his questions.

Much of the footage is taken inside the small flat occupied by Samuragochi and his wife. The one foray out of Samuragochi’s flat is to his lawyers, who contend, as Samuragochi does, his authorship at the conceptual level. Mori also goes out on his own to buttonhole Niigaki at a signing event, but Niigaki continues to refuse to meet Mori, and closes down the conversation.

Apart from that, we stay within the confines of Samuragochi’s flat. A member of a deafness society comes to offer support for Samuragochi as someone who had acquired hearing impairment after childhood and therefore has different traits to someone born deaf.

Two groups from TV companies come to negotiate an appearance of Samuragochi but nothing comes of these in Mori’s film. We see brief clips of TV shows, maybe ones from which Samuragochi was dropped, where Niigaki performs comfortably and Samuragochi is ridiculed. This is all grist to Mori’s mill depicting negative media.

At seventy minutes in to the film, we have found out little except that the media operate in packs. Then, in through the door walks Chris Beam, who does not speak Japanese, and a collaborator who does. He is subtitled as “D Heilly” but must be the same person who Beam mentions once as ‘my translator, David’.

It seems that these two have been seeking an interview for some time, had already spoken with the other principal actors in the story, and had got to Samuragochi close to their deadline, well primed. Beam starts the ball rolling with, ‘why did you create this story?’ Samuragochi is taken aback, remarks that they have come straight to the point, and remains dumbstruck. For an account of how the faking started from smaller beginnings, you will need to read Niigaki’s account, related by Beam. But the two visiting journalists push on. (By this point, David is not translating but pressing the questions in Japanese on his own.) They also want to know how the creative process worked between the two. How did they communicate to each other? Samuragochi says that he just gave the written instructions and Niigaki hardly ever said a word. But, David says, ‘Niigaki talked to us for hours’. Samuragochi might not have it entirely wrong when he says, ‘He must have gained the habit, later’.

Most of these instructions seem to have been destroyed, but Samuragochi produces a couple of pages of text and diagrams that relate to a piece, I think, unrealised. It’s at the level for a programme blurb for a non-musician. He adds that there were sound-clips of melodies.

But ‘how – David asks- ‘did you know you had got back something that related to what you conceived?’ First Samuragochi says he saw Niigaki’s fingers on the keyboard. When the improbable or impossible circumstances of this are questioned, Samuragochi changes his evidence and says he sung the melodies (which, of course, doesn’t even answer the question). David continues, ‘can you give an example of your melodies on a keyboard?’ This illiterate “musician”, has to admit that he doesn’t even possess one. Left with nothing but his voice, Mori spares us the “atonal moan of a melody” that, according to Beam, came forth after an hour.

The final part of Mori’s film shows a somewhat chastened Samuragochi actually buy a keyboard and attempt to make some music, which we hear in full. The most important point here is that this is the first music, apart from an unrelated opening tune, that we have heard in this documentary claimed to be about music and its creative process. Perhaps Japanese viewers would be familiar, but even they would surely need to hear the evidence of what Samuragochi still claims authorship. To me it’s an extraordinary absence from the film. Was there a rights issue? Was that what they went to see the lawyers about? Even if there is a dispute, there is such a thing as “fair usage” in Japanese copyright law and, in any case, it seems to be a point of agreement that Samuragochi paid Niigaki money in the process of their both ascribing the ownership to Samuragochi. But none of this is gone into in the film – certainly not the money- so I am left to speculate.

What we get by way of music is the new Samuragochi piece. It’s not entirely embarrassing. It has a sticky melody that I can still recall as I write and might be better than what passes in some soapy current-day Japanese films, but that’s not saying much. It’s certainly not of a standard of any concert music that anyone should want to sit down and listen to, or even hear more than once.

Mori makes this the ending of his film, along with bridging sections either side focusing on his relationship with his wife, who has stayed faithfully with him. His wife, Kaori might arguably be the subject of the film. We hear more of her voice than anyone else’s as she speaks everything that she also signs, mostly the words of others, until these final sections.

But in relation to the title of the film, we wouldn’t have much to show for 110 minutes, it weren’t for that late entry into the apartment. It was only as a result of Samuragochi being confronted with the nakedness of his argument, that he is goaded into getting a keyboard to give Mori an ending. Mori shows earlier a media circus masquerading as journalism. But there is no acknowledgement of real journalism – Chris Beam gets no acknowledgement in the credits, despite his piece being published well before the completion of the film. I need to add that the shunning is mutual – Beam mentions a documentary film crew but doesn’t name Mori. And it is Mori’s camera that shows that Beam’s collaborator is more than “my translator, David”. In the context of a story of unacknowledged collaboration, film-viewers seem invited to think about this.

Mori has elsewhere made the point that Asahara Shoko, the titular leader of the Aum sect, could, due to his disabilities, be encouraged by those feeding him information, into a heightened sense of paranoia. Leaving aside obvious differences in the cases, Samuragochi was also cocooned within the fictions he had made up, with no voice of dissent to listen to for years. His isolation after the revelations, including during Mori’s sojourn, was actually more complete until the arrival of those critical questions from New Republic, which seem, ironically, to have catalyzed some healing.

Mori’s own antagonism to journalists is specific. Out of this he has produced insights that those stuck on balanced reportage could never achieve. The turning away from the craft of journalism is actually a wider feature of the Japanese documentary movement that, I believe, gives it its strengths and weaknesses. By decentering the investigator or narrator in favour of quiet observation of the subject, much can be gained by the patient. It is an approach that foregrounds a personified subject but is not geared to answering a pre-ordained question.

This film is centred on a personified subject – taisho – who is outcast, but is then anonymously gate-crashed by toilers at the craft of journalism. It shows up the limitations of the “taisho” approach in ways ultimately to the film’s advantage. But it reads as a different film when watched with an innocent ear, than when knowing the story that Samuragochi had previously told. This, of course, echoes the “innocent ears” that heard different music by Samuragochi, as opposed to the music by not-Samuragochi. There is a complicity in the listening (and in all listening) that this film does not explore. Consider, for a moment, the list of “worst” films each year published by the critics of Mainichi shinbun. Reader, neither you nor I, no matter how bad a film we made, could get on this list. You have to be someone to get on that list of the most hated (last year, top of the list was the new Palme d’or winner Koreeda). Samuragochi, in Japanese media, was quite something. Now, it seems, Niigaki wants to be someone.