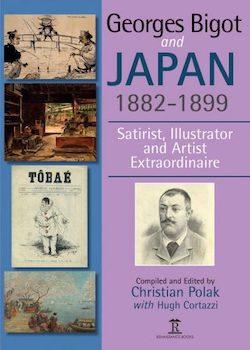

Georges Bigot and Japan,1882-1899: Satirist, Illustrator and Artist Extraordinaire

By Christian Polak with Hugh Cortazzi

Renaissance Books, 2018

ISBN-13: 978-1898823759

Review by Peter Kornicki

The French artist Georges Bigot (1860-1927) is not a household name in France or in England, but he certainly is in Japan, for Japanese schoolchildren see some of his caricatures in their textbooks. No wonder, then, that I had never heard of him until I chanced upon an exhibition devoted to his works at the Suntory Museum in 1972 during my first year in Japan as a foreign student. Since then there have been many other exhibitions, but it is only since 1981, when his archive was discovered still in the possession of his descendants, that it has become possible to draw upon the full range of his work. This lavishly-illustrated and beautifully-produced book by Christian Polak with Hugh Cortazzi makes the output of this talented artist and engraver easily accessible for the first time.

How did it come about that Bigot travelled to Japan and then became famous there? His widowed mother gave him an artistic upbringing and his talents eventually took him to the School of Fine Arts in Paris. There he became acquainted with Félix Régamey, who had returned to France in 1877 after a lengthy stay in Japan, and with others who were intrigued by Japan like Edmond de Goncourt. He had his first chance to see Japanese arts and crafts in the Japanese pavilion at the Exposition Universelle held in Paris in 1878. Unlike many who were inspired by what was on display, Bigot decided to make the long voyage to Japan to see for himself, and this proved to be the beginning of a stay in Japan that was to last for nearly two decades.

He arrived in January 1882 and, to keep body and soul together, initially taught watercolour and drawing to officer cadets at the Army Academy in Ichigaya. Later he was to rely on his ability to teach French or Western art to provide an income. He seems from his delightfully illustrated letters to his mother, many of which are reproduced in this volume, to have thrown himself into his new Japanese life in a way that suggests a long-term commitment. He began to learn the language and took lessons in calligraphy and Japanese music; he lived in a Japanese house with Japanese furniture and went around in Japanese dress and geta.

His first artistic responses to Japan were embodied in his letters home to his mother, but he also began producing paintings and engravings that captured the lives of foreigners living in Yokohama or the lives of Japanese, and as early as 1883, the year of his arrival, he published two volumes of engravings. He was by no means the only artist working in Japan at the time. A much earlier arrival was the Englishman Charles Wirgman (1832-1891), who was a correspondent for the Illustrated London News and who was the founder and editor of the Japan Punch from 1862 to 1887; Hugh Cortazzi has provided a useful account of Wirgman’s life and activities for this volume. Once Wirgman brought the Japan Punch to an end in 1887 Bigot launched his own satirical illustrated magazine, Tôbaé, which lasted for several years. His talents were also beginning to be appreciated in Europe, for he was engaged first by Le monde illustré and then by The Graphic to supply sketches of Japan. For The Graphic he travelled to the front in the Sino-Japanese War and provided a number of sketches which were published as engravings.

In 1899, however, he abruptly divorced his Japanese wife and returned to France with their son. The reason for his departure was the end of extraterritoriality in that year: as a consequence, he would have become subject to Japanese law and therefore censorship. Given that he had been unafraid of poking fun at figures of importance or of political commentary in his cartoons and that, under the influence of Nakae Chomin, he had become sympathetic to the liberal movement, he was probably right to suspect that his creativity would be stifled if he remained. Indeed, one of his sketches, titled ‘The revised treaties have been signed and foreigners are under Japanese jurisdiction’, shows a foreigner being led away under arrest, so the possibility of trouble was very much on his mind. Although he never returned to Japan, he did continue to depict Japan in his subsequent work, for example in a set of dinner plates showing scenes of Japanese life.

The bulk of this volume consists of high-quality reproductions of many of Bigot’s sketches, watercolours, oil paintings and engravings, and no summary, however elegant, can do justice to them. Amongst them are engravings from his first two albums which capture scenes of everyday life, such as a family riding in a rickshaw, porters carrying night-soil out of the city and children at a singing lesson. His oil and gouache paintings of similar scenes are arresting for their sympathetic portraits of ordinary Japanese, such as that of a heavily wrapped woman crossing the palace square. But there are many with an edge to them: some of them poke fun at the antics of the elite of Japanese society in Western dress, but others satirise the behaviour of members of the expatriate communities, such as a lecherous foreigner with a prostitute or an over-paid advisor to the Meiji government. Some again are overtly political and doubtless offended the government, such as one that showed Prime Minister Ito Hirobumi and Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru killing off an old man who was a personification of the Popular Rights Movement.

This splendid and very welcome book gives Bigot his due, and for that we are much in the debt of the authors for the conception and the contents. But we are also in the debt of Paul Norbury, the publisher, who saw the value and appeal of Bigot’s output and in response has produced a volume that is worthy of Bigot’s talents.