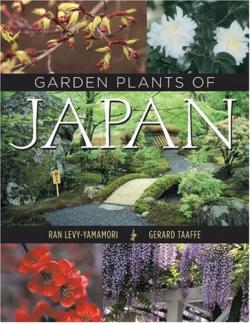

Garden Plants of Japan

By Ran Levy-Yamamori and Gerard Taaffe

Timber Press, Incorporated (2004)

ISBN 0-88192-650-7

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

When the Japan Society were preparing the Garden Bequest Exhibition for Japan 2001, we were conscious of the huge number of trees, shrubs and plants which had originated in Japan and which had become so popular in Britain. We tried without success to find a book in English which covered comprehensively Japanese Garden plants. Horticulturalists and gardeners, interested in shrubs and flowers of Japanese origin, will accordingly welcome this well produced and comprehensive book. I was at first put off by the price, but I was fortunately able to buy my copy at a much more competitive price through a well-known on-line book seller.

Charles Nelson of Norfolk (UK) in his foreword quotes the old story of the Japanese gardener who visited Britain long ago and was shown a Japanese style garden which had just been completed. He was duly impressed and commented: "We have nothing like this in Japan." The plants were wrong; they were not Japanese, but European substitutes. In fact, however, as this book makes clear vast numbers of Japanese trees, shrubs and plants which have come to Europe from Japan have become so ubiquitous in English gardens that we have forgotten that they are not indigenous to Britain. Perhaps in the garden which the Japanese visitor saw the plants had been used incongruously. I don't think that a Japanese visitor would be inclined to repeat this comment if he/she saw any of the numerous Japanese gardens so carefully planned and built by members of the Japan Garden Society.

In the introduction the authors begin by describing the four Japanese climatic zones ranging from subtropical to arctic and showing how these are divided on a map of the Japanese archipelago. "Japanese botanists estimate that there are between 5000 and 6000 plants native to Japan," but "a quick look at the plants used today in gardens of Japan shows that some of them are not actually of Japanese origin at all." Many came to Japan from China and Korea although "a certain number of garden plants may have existed to a limited extent in Japan prior to the plants being introduced from China and Korea." The authors stress that "many plants have symbolic meanings in cultural and aesthetical aspects of life in Japan" and note the way in which Shinto "helped to preserve Japanese plants" and trees. The importance of the four seasons in Japanese culture in general as well as in horticulture is explained. The introduction also includes paragraphs on the role of Japanese plants in gardens, on ancient trees and living national monuments, and on the traditional Japanese gardener with a short note on bonsai.

Japanese trees, shrubs and garden plants are listed in alphabetical order under their Latin names followed by the Japanese names in Roman script and their English names. The plant family is then shown together with information about distribution and a description of each plant. This is followed by notes on soil, light, pruning, propagation, hardiness, usage etc as appropriate. Related plants are described and there are colour photographs on every page. The largest section (over 220 pages) of the book is devoted to trees and shrubs. This is followed by sections on climbing plants, herbaceous plants, bamboo and sasa, grasses, ferns, and finally mosses.

An enthusiast for particular types of Japanese plants such as Japanese maples (acers) or camellias will find a description of most types they are likely to find in say Hillier's catalogues although the book cannot, of course, include all the detailed information contained in specialist books on particular species.

I knew that many Japanese plants were introduced to Europe by botanists such as Kaempfer, Thunberg, von Siebold, Fortune and Veitch, and that their names had become part of the official nomenclature, but I had not realised that, for instance, forsythia owes its name to the Scotsman William Forsyth (1773-1804) superintendent of the Royal Gardens of Kensington Palace. I had thought that ume, which grows in such profusion in Kairakuen at Mito and heralds the Japanese spring was "plum" but according to the authors it is really prunus mume which should be translated as Japanese apricot. Ume is written with the kanji bai in the three New Year decorations of sho (pine)-chiku (bamoo)-bai.