Japanese Prints: The Collection of Vincent van Gogh

Edited by Axel Rüger and Marije Vellekoop

Van Gogh Museum, Thames and Hudson, 2018

ISBN-13: 978-0500239896

Review by Beau Waycott

Published by the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, to accompany their 2018 exhibition Van Gogh & Japan, Japanese Prints: The Collection of Vincent van Gogh is a collection of enriching essays detailing Van Gogh’s relationship with Japanese art and the influence it had over him. Accompanied by beautiful, full-colour prints of both European and Japanese works, this is an art book that serves as more than a coffee-table piece, holding true and tangible value in its aesthetic design and intellectual property.

In the first chapter, Louis van Tilborgh (professor of Art History at the University of Amsterdam and senior researcher at the Van Gogh Museum) provides a brief biography of Van Gogh. In the winter of 1886-7, Van Gogh bought 660 sheets of Japanese art for trade; 33 years old, poor (thus having to share a Parisian apartment with his brother Theo, who regarded Vincent as constantly involved in ‘the most impossible and highly unstable love affairs’) and addicted to brandy and absinthe, Van Gogh was hoping to capitalise on the Japonisme that was in vogue amongst France’s commercialised middle class. With Japan having been hermetically sealed for decades, there was an immense interest in its culture from the 1850s onwards in France (although to a lesser extent in Van Gogh’s native Holland). Later in the text, Chris Uhlenbeck (Japanese art dealer and curator) discusses Van Gogh’s connection with Siegfried Bing, a Japanese art specialist who founded Le Japon Artistique, a trilingual journal on the interwoven relationship between Japanese art and the art noveau movement, which won Bing friendship and business with great impressionists such as Claude Monet, Alphonse Mucha and Paul Gauguin.

Van Gogh found the strong, central use of vibrant colour in Japanese prints, such as Utagawa Kunisada’s Actor Tying a Poem Slip to a Cherry Tree (fig.1), reflected the more positive life he was aiming to lead in Arles, Provence, as opposed to his earlier use of more subdued colours when affirming primitivist tropes.

fifth sheet of the pentaptych

Favourites All Together in Full Flower

Utagawa Kunisada, Edo, 1858

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

(Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Making a distinct loss on his investment, Van Gogh left Paris for southern France later in 1888, writing in a private letter to his brother that he viewed Provence as just ‘as beautiful as Japan’.

One reason for his move was a desire for a “pure”, more simple society which Paris just didn’t have. In Holland, Van Gogh had embraced the aesthetic idealisation of primitivism, coupled with extreme physical and mental austerity. In Provence, however, he lived a more light, musical existence with gaiety and freedom, and it is thought that the simple and uncomplicated nature of Japanese prints appealed to Van Gogh’s newly-found buoyancy. However, in late 1888, Van Gogh suffered a mental breakdown, leading to the ever-famous self harm of his ear, housing in an asylum, and later suicide. After this passage, Uhlenbeck explains how the prints were dispersed over Europe during the late 1800s through to the mid 20th century, when many prints came into the passion of the Van Gogh Museum.

The influence of works of nanga, a style made famous by artists such as Ike no Taiga, can clearly be seen in van Gogh’s The Rock of Montmajour with Pine Trees (fig. 2), with the use of a reed pen to create supple and distinct lines and the deft use of thickness to create depth and perspective.

Vincent van Gogh, Arles, 1888

However, it is the art creating during Van Gogh’s time in Provence that shows the most influence from Japanese prints. Appreciating the clear, lucid effect the prints held, Van Gogh attempted to replicate the distinct style of succinct and varied brushstrokes, but found the flat effect this creates difficult to achieve. As a result, he learned to incorporate more abstain into both his portraits and (more noticeably) his landscapes. Van Gogh also borrowed a large part of his stenographic vocabulary from nanga (a style of painting, also known as bunjinga, popularised in the late Edo period in which landscapes are depicted in basic strokes of monochrome ink), and began to work in dots, dashes, hatchings and short strokes of ink.

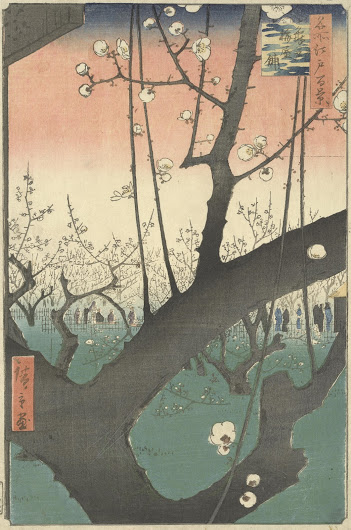

Uhlenbeck argues that the use of colour in Japanese prints had the greatest impact over Van Gogh, citing his detest at the fashion for agréablement jaunis (literally ‘agreeably yellowed’, agréablement jaunis was an artificial patina whereby dealers would bleach prints or soak them in tea to dull the colours, as preferred by French buyers, something Van Gogh did to not one of his prints). However, for an impressionist so interested in colour, Uhlenbeck has a fascinating passage on how there is no written evidence that Van Gogh ever remarked on the special effects used in Japanese prints, such as bokashi (graduated colour) or karazuki (also known as ‘blind painting’, a kind of gaufrage that adds patterns of relief to the paper or wood). Van Gogh wrote many letters about his Japanese prints, making it strange that he never remarked, for example, on Hiroshige’s use of bokashi to juxtapose reds, greens and blues, or the striking 3-D effect that karazuki gives to the hems of kimonos.

Whilst the successful use of bokashi to celebrate sublime stillness is evident in both Utagawa Hiroshige’s The Residence with Plum Trees at Kameido (fig. 3) and Van Gogh’s Flowering Plum Orchard (after Hiroshige) (fig. 4), Gogh never acknowledged any kind of interest in the traditional Japanese technique.

from the series One Hundred Views

of Famous Places in Edo

Utagawa Hiroshige, Edo, 1857

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

(Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Vincent van Gogh, Paris, 1887

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

(Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Furthermore, Uhlenbeck also notes that, especially for a collection purchased for trade, Van Gogh’s prints are strangely uniform, consisting primarily of portraits, and to a lesser extent landscapes, with over 40% of his pieces showing women (far more when you consider onnagata –male actors playing female roles in kabuki– a distinction Van Gogh is unlikely to have been able to make). Interestingly, Van Gogh did not own any shunga (erotic prints) or warrior prints, both of which were extremely fashionable at the time; his kachoga (prints of birds and flowers) collection was also very limited. Following this, Uhlenbeck details the distinctive printing techniques used, and Shigeru Oikawa provides an insight into the Western interest in chirimen-e (crépons) and the craftsmanship involved in their production, which is a well-appreciated addition, as this is a field uncommonly discussed in art literature.

Overall, Japanese Prints: The Collection of Vincent van Gogh is a rewarding book that deftly balances erudite and engaging writings with beautifully reproduced prints, including works of Van Gogh, Hokusai, Hiroshige and Kunisada. All images are full-size, and there has been no cropping or other digital manipulation, which adds to the thoughtful aesthetic of the book, which is truly beautiful, with each glossy page detailing fascinating intellectual material alongside exquisite artworks. Despite it’s relatively high price, the book will leave you with a warm feeling, the kind of feeling only the most delicate combination of stimulating, precise words coupled magnificent, pan-continental artwork creates.