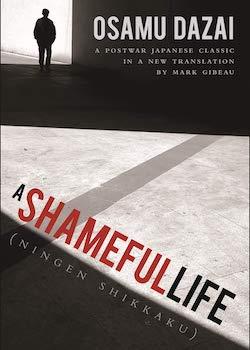

A Shameful Life

By Dazai Osamu

Stone Bridge Press, 2018

ISBN-13: 978-1611720440

Review by George Mullins

Ningen Shikkaku (translated as ‘A Shameful Life’) still persists as one of the most widely read and critically acclaimed novels in Japan. Ningen Shikkaku has been previously translated into English by Donald Keene (under the title of No Longer Human), but Mark Gibeau’s latest translation certainly provides a refreshing and interesting reconstruction of this Japanese classic. The short novella follows the inner confessions of an outwardly jovial, but deeply troubled protagonist. Readers are transported behind the façade of young Oba Yozo, an alcoholic Tokyoite that fails to meaningfully relate to the modernising world surrounding him. The self-destructive behaviour of the protagonist seems to reflect writer Dazai Osamu own tormented world in this deeply confessional novel.

The book takes the form of a Japanese ‘I-novel’, with a little plot or direction but a great emphasis on the thoughts and feelings of the protagonist. The book is comprised of three journals which lay bare the tragic tale of Oba Yozo’s life. The journals acts as a first-person account of the downward spiral of the protagonist. Each journal is increasingly more depressing and weighted than the last, as Yozo struggles to fine his place within the alien world that surrounds him. The shortness of the novel mirrors the fast paced destructiveness of Yozo’s own life. Through the directness of the journal accounts, we are placed in a privy position to witness the emotional turmoil of this shameful life. Despite being a shorter book, it possesses a high concentration of tragedy and emotional gravitas.

To begin with, a young Yozo is afraid of human interaction and cannot comprehend the social world around him. He masks his insecurities by developing a jovial demeaner and becomes the entertaining class clown to all his peers. His feigned positive attitude, however, results in feelings of guilt over a lack of truthful to those around him. He becomes tormented by the mask that he conceals his true emotions. As he grows up, Yozo moves from his family home in rural Northern Japan to pursuit a career as an artist in Tokyo. He is attracted to the debauchery of the Tokyo lifestyle and becomes an alcoholic. Alcohol becomes a way of nulling his depressive thoughts and a method of escape from his inner self. His relationships with women are strong and intense: he has many sexual encounters with prostitutes and develops deep connections to many women. But ultimately his self-destructive tendencies mean his life is doomed to fail. He tragically attempts a double suicide, which fails and leaves his delicate life in shatters. He also joins an underground Marxist group and develops a morphine dependency. His destructiveness leads him down a narrow path, and he ultimate squanders his family wealth and is left in a miserable, isolated position. The novel bleakly concludes with Yozo’s admission to a mental hospital at the early age of 27. The charisma and artistic potential of the young man is ultimately wasted. What is left is the depressing picture of the shell of the man that was once Oba Yozo.

The parallels between Yozo and Dazai himself cannot be ignored. Dazai’s own life was also one of tragedy and exhausting emotional turmoil. He himself struggled with identity and depression, and he too developed intense relationships with troubled women. Through morphine addictions and alcoholism, he followed the same path to hell as Yozo. Still in his 30s, Dazai and his lover, Torie Yamazakai, tragically committed suicide together. This came only shortly after the release of his masterful work, A Shameful Life. It is therefore possible to see this novel as a quasi-auto-biography: Dazai was spilling out his own misanthropic and bleak world views into the emotionally dense novel. This certainly aids to the powerfulness and tragedy of this masterful work.

The novel manages to firmly place it’s context in a changing, post-Meiji period, Japan. The glitz and glamour of modern life is undercut with the sinfulness and anomy of Tokyo’s dark underworld. One can’t help but seeing this contrast reflected within Yozo’s very being. The positive outward persona of Yozo, contrasted with the inner turmoil festering within, is a powerful dichotomy. Surely writers such as Mishima, in Confessions of a Mask, took influence from this bleak portrayal of the duality of Japanese social life. Massive changes may have led to increased modernisation and a more European way of life, but what impact did this have on Japanese culture and people’s identities? Dazai, along with other influential Japanese writers such as Kawabata and Tanizaki, attempts to confront this issue. However, A Shameful Life is still relevant beyond it’s contextual setting of modernising Japan. The theme of the individual struggling to survive in wider society is certainly a reoccurring phenomena, both spatially and temporally, and therefore this novel will still holds relevance for contemporary audiences. This explains why it has been widely adapted in anime and live-action form in Japan, and why the dark introspective writer still has a large following to this day.

As the author notes in a brief conclusionary statement, audiences may wonder why Dazai’s work has been chosen to be re-translated in the 21th century. Especially considering that an already fantastic translation of Ningen Shikkaku, provided by Japanologist Donald Keene, exists. Aside from wanting to bring renewed interest in Dazai’s penmanship, Gibeau stresses the differences between English and Japanese, and the large effect the translator’s interpretation plays in the re-construction of a Japanese book. Each translator of Dazai’s work will inevitably strive to illuminate different themes and interpretations of the book. Compared to Keene’s famous translation there are differences: Gibeau attempts to emphasise the voice of the protagonist Yozo, resulting in powerful feelings of intimacy and directness. Therefore, I believe Gibeau’s translation is a welcome edition and supplies readers with a unique take on Dazai’s compelling novel. I share Gibeau sentiments, believing that A Shameful Life is an important novel, written with an abundance of emotion and craftsmanship. 70 years on, Gibeau’s translation shows that this captivating novel is still as relevant and powerful as it was on the day of its initial release.