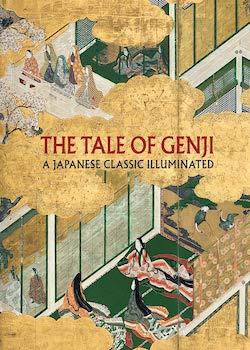

The Tale of Genji: A Japanese Classic Illuminated

By John T. Carpenter and Melissa McCormick with Monika Bincsik and Kyoko Kinoshita

Preface by Sano Midori

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019

Distributed by Yale University Press

ISBN-13: 978-1588396655

Review by Timon Screech

SOAS, University of London

It is customary to refer to the Tale of Genji as the world’s first psychological novel. The case can be argued, for over the course of its 54 chapters, the reader follows the lives, states of mind and emotional shifts of a range of characters. Prince Genji dies long before the end, and the tale continues with his son. ‘Novel’ is a modern word and appeared many centuries after the Tale was written, and on the other side of the globe. The Japanese term is monogatari, ‘talking about matters’. The title of Genji monogatari may or may not have been assigned by the author, but the work was soon known as such, and the designation defined the work’s meaning ever after. It focusses on the eponymous hero and ‘matters’ surrounding his life.

The monogatari became an established form well before the year 1000, and some examples from that early period survive. Others are known only from references in other fictional texts, or court diaries. Some monogatari speak of ghost and monsters, or far-away lands, but the majority address the world in which the reader lived. They cover the ‘matters’ of real life, and unfold in the types of building in which readers lived in, with people they might plausibly meet, and the thrills and anguishes that attended their daily round. The ‘they’ was the tiny number of literate courtiers – whose attitudes towards people beneath them, when such persons even appear, is deplorable. Some monogatari, like early novels, offered moral lessons, about hubris, immorality or other wickedness, and some characters gets their comeuppance, but not always, and Genji has only the subtlest advice to offer here. It depicts a world governed by karma where spirits can help or hinder, but only in ways that would have seemed logical to readers of the time, and on the whole they still do today. It is the complexity of emotions that is to the fore, and which makes Genji so fascinating.

Interestingly, within the tale is an episode in which Prince Genji stumbles on ladies reading monogatari, and offers some thoughts. The extract has been repeatedly quoted to illustrate how readers probably understood the genre at the time. Genji makes a positive contrast with histories, which deal with event and fact. Genji is made to say that, indeed, monogarari and their emotions can be the better way to understand human existence. It seems implicit that histories were male domains, while monogatari were for women. However, this gender division has recently been challenged. It was certainly the case that men read monogatari too, and also wrote them. There was no reason, then or now, why ‘matters’ were a female preserve. However, the Tale of Genji was itself written by a woman, that is, by a court lady, who could not have known as much about ‘history’ as a learned male might. In keeping with expectations of the time, the author’s name is not recorded. Ladies did have names, but these were taboo outside the family, so they were known by sobriquets, taken from a feature of their apartments (eg, ‘lady of the wisteria tub’) or the title or office held by a male relative. The author of Genji must have had a relation in the Office of Rites (shikibu) as Shikibu is the name by which she was known. The chief female character in the Tale, whom Genji idolises, pursues and (since his is a child) rears, is referred to as Murasaki, ‘purple’. Life follows art, so this name was adopted, and the author became widely known as Murasaki Shikibu. Some earlier English discussions call her Lady Murasaki. Historians can discover hidden given names, and it is proposed that Murasaki Shikibu was Fujiwara no Kaoruko. Certainly she was from that powerful court family, though a minor branch of it. Her father, Fujiwara no Tametoki, did indeed serve in the Office of Rites. The identify of her mother is not clear.

We know a little about the historical Murasaki Shikibu from comments by other ladies, many of whom kept diaries (Murasaki kept one too). She must have been reclusive, or at least capable of isolating herself from court intrigues long enough to concentrate on a book well over 1000 pages in a modern edition. Frustratingly, it is not quite certain when she did this, or how long she took. Murasaki is known to have lived from about 975 to about 1016 (though some date her death as late as c. 1130). She probably lived to about the age of 40. She went to court in 1005 to serve the empress, some dozen years younger, and whose father, Fujiwara no Michinaga, was a distant kinsman of the writer and the most powerful person at court. The empress encouraged the literary arts. After a short number of years, having born sufficient sons, she retired, rather notionally, spending time outside the Capital. Murasaki Shikibu seems to have accompanied her, and a myth was generated that she wrote Genji at the Ishiyama Temple overlooking Lake Biwa. Surely it took a decade to complete. The first refence to the tale dates to 1008, when it was underway. A reference from 1020 refers to 54 chapters, meaning it was finished. The assumption is that the work was concluded in 1019. At once it was recognised as a stunning achievement, and it was an immediate classic.

In recognition of the 1000th anniversary the Metropolitan Museum has mounted a glorious exhibition. Many people (including the present reviewer) will not be able to get to New York, but the Met has produced a fine accompanying volume. Although a catalogue, it is likely to enjoy an independent and lasting existence after the exhibition is over. The coverage is large, from some of the earliest extant transcriptions, and pictures on Genji themes, including masterpieces from US and Japanese collection, through later works refencing or illustrating the tale, along with the wealth of artefacts and household luxuries on Genji themes, right up to manga versions. Other than the Bible, Genji has arguably generated more visual culture than any single work (and the Bible isn’t a single work). There catalogue provides a comprehensive overview across all major types and schools and materials.

It was not long before Genji became too hard to read. Its text was unfathomable to later generations, especially those without access too – or perhaps little sympathy with – the self-obsessed court of c. 1000. Only major works of retrieval scholarship, in the 17th century brought Genji back into the orbit of actual readers, though even though, its length was prohibitive. People knew Genji more than they read it (also like the Bible). Stories were detached, which also allowed problematic parts to be obscured (such as Genji’s philandering having corrupted the legitimate imperial succession). Educated people knew Genji themes, one of two per chapter, and could recognise episodes from well-established pictorial types, or from rebus-like analogies. The Tale of Genji is as much, if not more the domain of art history than of literary history.

More than lining up Genji artworks, the Metropolitan Museum has sought to reinterpret. The catalogue entries are arranged into essays, some on unexpected themes. One is monochrome illustrations, unexpected because Genji is associated with the colourful yamato-e (or waga) manner. Much emphasis is also placed on Buddhism, and this is welcome. Over history, clergy sought to come to terms with the fact that all monogatari are ‘lies’, and Genji, being so widely known, was the worst offender. Religious services were conducted to console the author as she languished in hell.

In this catalogue, and even more in the exhibition, we have the best of Genji objects, and with them, the best of contemporary Genji scholarship.