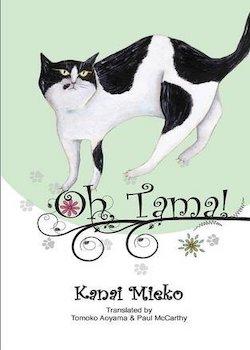

Oh, Tama!

By Kanai Mieko

Translated by Aoyama Tomoko and Paul McCarthy

Kurodahan Press (2014)

ISBN-13: 978-4902075670

Review by Poppy Cosyns

From the pompous narrator of Soseki’s epic satire I Am A Cat, to the elusive interloper in Hiraide Takashi’s poignant novella The Guest Cat, Japanese literature has more than its fair share of felines. Knowingly positioning her work within the cannon of what translator Paul McCarthy calls “cat literature”, celebrated poet and novelist Kanai Mieko has peppered this novel with little nods to classics of the genre. To name a couple: a cameo from a cat called Lily, will ring a bell for those who have read Tanizaki Jun’ichiro’s A Cat, A Man and Two Women and the title is itself a play on Uchida Hyakken’s ode to a missing cat, Oh, Nora!

The second in a series of works set in Kanai’s own neighbourhood of Mejiro, in downtown Tokyo, this novel – which won Kanai Japan’s Women’s Literature Prize – delves into the dysfunctional lives of a cast of eccentrics who live in the area. Some of these same characters crop up elsewhere in the series, though each novel has a standalone narrative. As the story starts, freelance photographer Natsuyuki Kanemitsu has a heavily pregnant cat called Tama unceremoniously dumped on him by his friend, the affected and slightly vacuous Alexandre. There is nothing particularly remarkable about Tama, who Kanai presents as a typically aloof stray. As the novel progresses, however, her significance gradually emerges. From her position on the side lines of the story’s action, she becomes a grounding influence on Natsuyuki and his oddball band of associates, while also embodying the notion of the unconventional family that is at the novel’s heart.

Natsuyuki’s friends are drawn with varying degrees of detail, as they wander in and out of his modest apartment in Mejiro. There is the pretentiously self-styled Alexandre, a model and occasional porn actor, who at various points in the story avails himself of Natsuyuki’s reluctant hospitality. An unashamed intellectual lightweight, he objects to his friends’ tendency for niche cultural references and appears to float through life having shrugged off the burdens of convention and respectability. The latter’s sister Tsuneko – who, like Tama, is pregnant – is the subject of much gossip among Natsuyuki’s circle, as they debate who is most likely to be her unborn baby’s father. The reader never meets Tsuneko, allowing us to share in the atmosphere of intrigue and outrage that surrounds her, without ever hearing her story first hand. Spiritually twinned to some extent with the equally silent Tama, Tsuneko represents the archetypal wayward woman and the antithesis of the Japanese ideal. The hypocrisy of the male characters in their criticisms of Tsuneko suggests a feminist undertone to Kanai’s writing here.

The central character of Natsuyuki is rather thinly drawn, with Kanai inviting her reader to draw their own conclusions about him, through description of his decisions and the company he keeps. His fixation with the fictional photographer and “unknown artist” Amanda Anderson – whose background and photographic style is related in impressively believable detail – is perhaps the most remarkable eccentricity we discover about our protagonist. Natsuyuki is initially striving to be taken seriously and to appear relevant among his contemporaries in the art world. He eventually concludes however, that he would rather maintain this obscure finding as part of his private fantasy and that to share it would only dilute the fascination it holds for him. His eventual dedication to the care of Tama and her litter of kittens appears to suggest that only through the nurturing of life, can these selfish and pretentiously inclined characters, hope to find any way out of their existential crises.

As with much of Kanai’s work, Oh, Tama! takes a bit of getting into. Her experimental, almost stream-of-consciousness style is abundant in examples of wordplay, literary references and characters getting their wires crossed. As an example, much of the chapter titled ‘Wandering Soul’ is given over to the characters’ unfocused ruminations on film makers Daniel Schmid and Jean-Luc Godard and novelist Vladimir Nabokov. Translator Aoyama and McCarthy have conquered the formidable challenge of communicating Kanai’s famously skittish tone and love of the double entendre and happily, once one has settled into the peculiar rhythm of her prose, the novel becomes an enjoyable and often very funny read. It must be said, however, that those who like their fiction with a meaty plot to get stuck into, had better look elsewhere. Kanai’s unremitting sense of the absurd and the subtly drawn interactions between her characters are what make this a worthwhile read, the plot is gossamer thin.