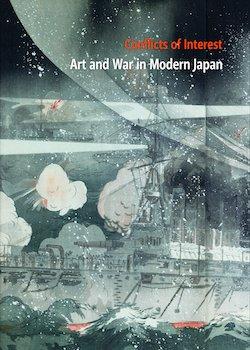

Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan

By Philip Hu, Rhiannon Paget, Sebastian Dobson, Maki Kaneko, Sonja Hotwagner and Andreas Marks

University of Washington Press (2016)

ISBN-13: 978-0295999814

Review by Laurence Green

Released to accompany the Saint Louis Art Museum’s collection of over 1,400 objects relating to the Japanese military (largely focusing on colour prints), there lies a neat play of words at work in this lushly illustrated exhibition catalogue. Is it the literal conflict of interests between two rival nations, set against each other in open, bloody conflict? Or perhaps it is the conflict of interests within ourselves as we – viewers at a calm, composed remove from the horrors depicted – look on and find a kind of fascination, if not outright beauty, in these depictions of violence and martial prowess.

It is the latter of these that perhaps makes this collection of artworks so visually arresting. With a core focus on the Sino-Japanese (1894-1895) and Russo-Japanese (1904-1905) wars, these prints take us through the gamut of Japan’s intensely rapid period of modernisation from the beginning of the Meiji Restoration in 1868 to the aftermath of Pearl Harbour in 1942. As such, we not only get a vivid sense of a fast-moving evolution in military technology, but a palpable air of the idea of ‘modernity’ itself; of new ways supplanting the old as Japan rushed to equip and attire itself in the guise of a powerful, Westernised nation.

The catalogue’s introduction gives ample space to dismissing the received idea that Japanese prints of the Meiji era (1868-1912) were somehow an elegiac last gasp for the woodblock format, so popularised in the ukiyo-e of the Edo period (1603-1868). But perhaps there is some argumentative weight to be found in why this misconception holds such currency in the first place; that it is the very romanticism of this ‘last gasp’ image that makes it so compelling to Western audiences numbed to countless re-presentations of undisputed masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige. In these Meiji era prints, we find two distinct worlds collided together: the classical two dimensionality and linework of the woodblock print paired with the cold steel of battleships and sleek black Imperial uniforms. Just as the original proponents of the Japonisme movement in the 19th century were charmed by the exoticism of ukiyo-e, so too are we drawn in by the ‘newness’ and unfamiliarity of the prints contained here.

As such, this catalogue is not only a story of the prints themselves, but of those who collected them at a time when they were deemed unfashionable. In a fascinating opening essay by Philip K. Hu, we are presented with a contrasting picture between Western and Japanese collectors – the latter of which remain far more shrouded in mystery as a result of the culture of Japanese art collecting in which collectors maintain a high deal of privacy and auction sales records as well as provenance data are rarely available. The picture is one of a handful of specialist, private galleries and one-off exhibitions, as opposed to the more public-orientated spirit of Western gallery exhibition.

In the spirit of ‘collection’ an interesting anecdote is repeated across two of the essays, involving renowned Japanese novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichiro. Recalling with nostalgia the Tokyo of his youth, he wrote in 1955:

‘The Shimizu-ya, a print shop at the corner of Ningyo-cho, had laid in a stock of triptychs depicting the war, and had them hanging in the front of the shop… There was not one I didn’t want, boy that I was, but I only rarely got to buy any. I would go almost every day and stand before the Shimizu-ya, staring at the pictures, my eyes sparkling…’

Tanizaki’s words will no doubt feel familiar to collectors the world over – the sheer thrill of desiring that which one does not have. It is an odd sensation to feel such beauty emanating from such horrific subject matter. But beautiful these pictures undeniably are, even more so when one considers the craft put into their creation, something which the catalogue’s incredibly comprehensive bibliography and reference notes amply elaborates upon. And yet, as these prints lost market-share in the face of rising sales of photography and picture postcards, the very thing these prints were able to offer becomes more plain: the power of fanciful, fantastical imagery to illustrate what which would be impossible or impractical for a photograph to; to immerse the viewer in the action with an intensity and ‘closeness’ that practically leaps from the page. Indeed, it is rather amusing to see that the extent in variety amongst the prints presented here even reaches to a kind of cut-out, assemblable 3D diorama, complete with gluable tabs and how-to guide.

The idea of an aestheticised modernity, fully embodied by the nature and possibilities of contemporary media technology is examined in further detail by Rhiannon Paget in an essay looking at how imagery of Japan’s wars in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was consumed in the West. With frequent references to popular publications of the time such as the London Illustrated News, we are given a taste of the thrills the media evidently saw in the awakening of the ‘slumbering’ Eastern nations and the promise of a ‘good battle’ between Japan and China. Later, she observes how media in both the West and Japan quickly envisioned the attractive, aristocratic young women who worked as nurses for the Japanese Red Cross as eroticised figures – a modernised, idealised evolution of the bijin figures who were such a staple in the earlier ukiyo-e.

Rounding off the collection of essays, Maki Kaneko focuses on the case of the ‘Three Brave Bombers’ – a semi-mythologicised trio of young Japanese soldiers in the early 1930s who, each carrying a tube-like Bangalore torpedo made of bamboo, blew themselves up against a Chinese barbed wire fence in an attempt to breach it. The image and power of this story spread with an almost meme-like virality across all forms of media in Japan at the time and was even adapted into a Kirin beer advert appended with the tagline: “Charge! Charge! Kirin Beer Always Makes a Path for the Future”. Kaneko observes this dark humourism as an example of the ero-guro (erotic grotesque nonsense) culture of hedonism found in 30s Japan, an atmosphere suffused with the glory and sensuality of death, feeding directly into the wider climate of militarism.

It is against the backdrop of discussions such as these that we can take in the entire spread of this catalogue (a weighty one, at over 140 individual plates). Time and time again, society has shown that people invariably favour media-constructed images to reality – or at the very least, that media (whatever its format) contains astounding power to engage us as viewers and subvert our way of thinking. It is the very nature of the Japanese print as popular media that makes it so impactful. These images were designed to entertain, to enthuse, to shock. With hindsight, we look back on them and see the deeply sinister nationalism and cruel jingoism written plain. And yet, their visual, artistic vibrancy remains undiminished, their capacity to offer a window (albeit an often grossly exaggerated or subverted one) onto a lost world unerringly engaging. With the British Museum’s landmark 2017 Hokusai exhibition meaning awareness of Japanese prints amongst a general audience has never been higher, Conflicts of Interest presents a fascinating counterpoint, bringing the medium and us as viewers into modern times with a sharpness and clarity that is thrilling to behold.