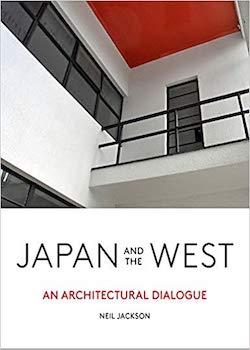

Japan and the West: An Architectural Dialogue

By Neil Jackson

Lund Humphries Publishers (2018)

ISBN-13: 978-1848222960

Review by Andrew Nishiyama Taylor

In our age of physical and digital infrastructure, it is difficult to imagine a time when the corners of the globe were unconnected or undocumented. There are few places in the twenty-first century for which the mere naming of a destination does not evoke vivid imagery, perhaps with a particular landscape or natural wonder at the fore. Consider those images for longer and something more synthetic will begin to advance: the architecture and built environment of a place also plays a crucial role in our perception of a nation’s identity. How does that architecture emerge to become characteristic of a place, particularly through centuries of ever-increasing globalisation? Does the introduction of foreign influences enhance, dilute or eradicate the vernacular of a place?

In 2005, architect and historian Professor Neil Jackson began researching the Western world’s interactions with Japan and the resulting impacts on their respective built environments. Entitled Japan and the West: An Architectural Dialogue, Jackson’s book opens with a passage on the first Japanese emissaries in Europe in the late sixteenth century. Through their gifting of two folding screens, decorated with depictions of a castle near Kyoto, the envoy provided the Pope in Rome with the Western world’s first glimpse of Japanese architecture. From this early encounter, the reader is taken to Dejima in Nagasaki during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: the sole port through which Japan tightly controlled its commercial (and, less conspicuously, intellectual) exchanges with the outside world during the Edo period (1603-1868). With Dutch traders as the principal conduit, Jackson details how everything from book frontispieces to furniture served to present Europe’s then-prevalent neoclassical style to the Japanese, while journal accounts and drawings brought observations of Japanese buildings and interiors back to Europe. This delicate courtship between East and West sustained until 1854 when, with the signing of the Convention of Kanagawa, the ports of Hakodate and Shimoda were opened to the United States, effectively bringing an end to the period’s isolationist policies and, crucially for the theme of Jackson’s book, allowing an intellectual and stylistic dialogue to gain pace and flourish during the Meiji era (1868-1912) and beyond.

The opening of Japan caused a burst of Japonism through international exhibitions in Austria, France, the UK and US in the second half of the nineteenth century, all vividly rendered in Jackson’s text. Despite displays ranging from fanciful imitation to faithful reproduction, these exhibitions generally had the backing of the Meiji government in recognition of the soft power they promoted. It is fascinating to imagine how domestic designers, most of whom would have been unable to travel to Japan themselves, would have drawn inspiration from seeing architectural elements and motifs on display at these exhibitions to create works both inauthentic and innovative, neither ‘East’ nor ‘West’. At the same time in Japan, the end of isolationism extended Western-style architecture beyond the confines of Dejima, even though, despite overtly colonial appearances, such buildings had underlying Japanese construction techniques and materials (Jackson cites Thomas Blake Glover’s house in Nagasaki as a prime example).

This idea of hybrid design, something which has Japanese or Euroamerican origins but, ultimately, through its transposition between East and West belongs to neither, is a key theme of Japan and the West which pervades through the rest of the book. As the twentieth century unfolds, Jackson draws on everything from the upscaling of Japanese temple architecture for modern building typologies, to the Japanese influence on the Bauhaus movement, to post-and-beam residential architecture in Australia and the US, to the archipelago’s embrace of Brutalism, in order to demonstrate just how interwoven the dialogue became by the end of the millennium and the pluralities of its manifestation.

Although the number of individuals involved in bridging Japanese and Western architecture over centuries is too great to detail, Jackson seamlessly incorporates relevant biographical passages for key proponents, and of particular interest are those whose works will likely resonate with contemporary readers. The British architect Josiah Conder (1852-1920), whose works came to typify the Westernisation of Japan in the Meiji era, may be best known to Tokyo residents and visitors for his Kyū-Furukawa Gardens (1917) in Kita ward and Mitsubishi Ichigōkan (1895), credited with beginning the conglomerate’s development of the Marunouchi business district. Tatsuno Kingo (1854-1919), Conder’s student, was prolific in his neoclassical designs for the Bank of Japan, notably its headquarters in Tokyo (1896), as well as the Dutch-influenced Tokyo Station (1914). Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) occupied a unique position in the dynamic between East and West: he referenced Japanese architecture in the deep overhanging eaves of his Prairie houses in Oak Park, Illinois (around 1900-1910) before his approach was introduced to Japan in his commission for Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel (1923). The inclusion of the Library at the Glasgow School of Art (1909) by Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) is a poignant reminder of the work’s importance in British-Japanese design exchanges. Concluding with Pritzker Prize-winning SANAA, known in London for their design of the 2009 Serpentine Pavilion, Jackson highlights the international role of Japanese architects in the twenty-first century and reflects on whether Japan has been able to maintain its own architectural traditions through modernisation and globalisation.

Japan and the West is carefully structured around the Shogun (Edo), Meiji, Taisho (1912-1926) and Showa (1926-1989) periods and the painstaking research that has gone in to its creation is clear. Despite its impressive scale and scope, the narrative is fluid, brisk and a pleasure to read, adding to the book’s broad appeal. To those who have visited Japan, the book will give explanation to the country’s (particularly Tokyo’s) at-times idiosyncratic urban built environment. To a broader readership, Japan and the West will add depth to the resurgent interest in the Japanese architecture of popular publications and recent exhibitions. Finally, to architects and designers, Jackson sheds light on innovation and originality in the creative process and reveals Japan to be a nation which will always sustain a unique sense of place and never cease to inspire.