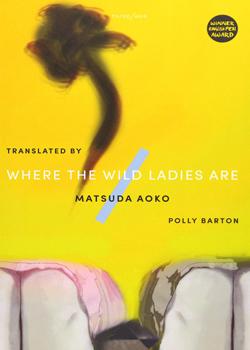

Where the Wild Ladies Are

By Matsuda Aoko

Translated by Polly Barton

Tilted Axis Press (2020)

ISBN-13: 978-1911284383

Review by Charlotte Goff

What’s stopping you from getting the life you want? For the protagonist of Smartening Up, the second in Matsuda Aoko’s newly translated ghost stories, it is her hair. If only she had remembered to epilate, she would surely never have been dumped. If only she had long, golden locks, the rest of her life would fall into place. It takes a visit from her dead aunt to make her rethink her relationship with her hair, her ideal self, and the wisdom of locating her self-esteem in the approval of others. These are not your average ghost stories. They probably won’t leave you chilled to the core – though, as translator Polly Barton points out, their chilling effect is one reason that Japanese ghost stories are traditionally told in summer – but will instead leave you amused, moved, and hopefully empowered.

Of course, what we consider scary is subjective. In Nakata Hideo’s Ring, Sadako emerging from the TV with long, black hair hanging before her is one of the film’s most chilling images. In a more mundane way, ‘unruly’ hair has come to be feared by women the world over. To ride the Tokyo underground is to be stared down by ubiquitous hair removal ads, and in 2018 a Japanese advertising agency made international news for repurposing models’ armpits as marketing space. For our narrator in Smartening Up, the rejection of this ideal is a moment of triumph. This is a ghost story but, more than that, it is a love story. Learning to embrace the power of her hair, our narrator swaps self-hatred, and a longing for everything western, for a renewed love for herself and her Japanese-ness: we see her move from consuming Dean and Deluca groceries from a Scandinavian-style table while watching a ‘romantic comedy starring Michelle Williams’, to drawing inspiration from the tale of Kiyohime, visiting the local sento, and nourishing ‘the black mass’ inside her.

It is typical of Matsuda’s tales that the transformation she undergoes is as open to the living as to the dead, and the two worlds are so interconnected throughout these tales that it can take time to work out which characters are dead. When they appear, Matsuda’s ghosts are more likely to be helping the mortals than haunting them. They are benevolent, if preternaturally persuasive. They might turn up at your apartment unannounced, but the worst that will happen is you feel obliged to share the expensive red bean sweets you had been saving for a special occasion, or end up with a few unnecessary toro lanterns. Best case scenario, you – you who are fed up with men and dumped your boyfriend after realising that living with him felt like accumulating a mound of pebbles inside – may land a spectral girlfriend who will massage your feet each night and disappear by morning. Unlike ghouls who spend their afterlives avenging past grievances, Matsuda’s ghosts have dreams and aspirations, and we see them working towards these under the guidance of the mysterious Mr Tei.

Matsuda’s tales are a joy to read, and more than live up to their promise to be feminist retellings. The real monsters in this collection are not the ghosts themselves, but the spectres created by a capitalist, patriarchal society: workplaces where women are chronically under-valued, vicious rumours which hound a single mother, and the beauty industrial complex which produces and profits from women’s self-hatred. Matsuda retains key elements of Japanese traditional folklore, such as shapeshifting, and the harmonious relationships between living and dead, while reimagining the issues they might have in contemporary Japan.