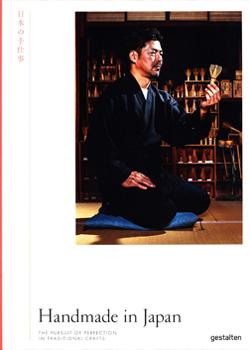

Handmade in Japan

By Irwin Wong

Gestalten (2020)

ISBN-13: 978-3899559927

Review by David Tonge

‘There are wonders to be found up and down the length of the Japanese Archipelago, if you know where to look’ (p.6)

If like me you have an appetite for exploring all things related to Japanese design and crafts, Irwin Wong’s introduction to Handmade in Japan will surely prompt you to investigate further.

Wong is a well-known commercial photographer based in Tokyo, so on the book’s announcement I knew it would be filled with evocative images of Japan and its craftspeople. And given publisher Gestalten’s reputation for beautiful design and craft monographs I simply had to buy it.

Like many books of its kind, it is divided into geographical chapters from Hokkaido in the North to Kyushu in the south. This allows you to dive in at random according to your interest in either craft or region. Each chapter begins with a brief introduction of that region explaining the interconnectivity of geographical, political and historical factors that shape it, its crafts and industries up to the present day.

For example, Kyushu’s proximity to Korea via the Korean Straits and Taiwan in the Southwest led to a region adept at trading with and ultimately becoming a gateway to foreign cultures. This was instrumental in the development of Japan’s thriving export ceramic industry and conversely the introduction of overseas design, materials and taste to the Japanese consumer. If you are lucky enough to visit Fukuoka in Kyushu, you will be able to feel these influences on its architecture, food and fashion.

In each case Wong describes in simple language the fascinating relationship of Japan’s natural resources – clay, bamboo, water etc – to each of the regions, therefore explaining the growth of regionally specific crafts. Those of us who have spent any time in Japan will know that each region has its own meibutsu (specialities), often in the form of edible gifts at railway stations. But if you ever wondered why for example, Gifu makes great wagasa (Japanese paper umbrellas), this book shines a light on the complex relationships that combine to make this possible.

There are many books about Japanese crafts. As a designer with a 25-year connection to Japan I have read many of these. My usual ‘go to’ is Japanese Crafts by the Japan Craft Forum, published by Kodansha. Like Wong’s it navigates Japan’s craft culture region by region and while it is incredibly thorough it is also rather academic. This is great if you are writing a thesis, but it is unlikely to get you planning your next trip! In contrast where Handmade in Japan scores highly is its focus on the craftspeople and their personal stories. These stories are warm and engaging giving the reader an insight into the lives, sacrifices and in many cases the generational commitment families have made to their craft and the region they live.

Wong uses his photography and simple descriptions to highlight the processes used to create these wonderful objects, often orally transmitted, generation after generation. For instance, If you were, sadly, never able to visit the castle town of Miyakakonojo in Kyushu to observe traditional long bow making, after reading Wong’s description you would be able to understand the fundamentals of the process and the environment within which it flourished. And furthermore, after hearing bow maker Kusumi Sumihiro say ‘I’ve concluded that this shape is the best after 33 yrs of experience’ (p.20) you would begin to understand the patience and commitment required to be a craftsperson in Japan.

All of these makers stories are well drawn but a particular favourite of mine is that of Tokyo’s Sumida based tabi (Japanese socks)[1] maker Meugaya. Owner Ishii Yoshikazu is one of the last remaining bespoke sock makers in Japan. From his shop in Sumida, an area known for its many artisans, this fifth-generation artisan, his wife and son are involved in every stage of the process. In order to make a pattern they painstakingly measure their customers feet in 20 places on each foot, ensuring the tabi fit perfectly. Many stages later and after completion the tabi are worn for 3 months as a trial pair before adjustments are made. New customers are required to order 6 pairs thereafter the measurements are ready to make further pairs. With clientele from the nearby geisha community and luminaries from the Kabuki theatre world Meugaya stays in business due to its unbelievable customer service.

What I love about this particular story is the combination of craft and commerce which for me encapsulates the Japanese mercantile mind set – craft is not just for looking at, it’s not for art’s sake. It needs to function well, sell and in many cases maintain the family tradition.

Each of the 33 stories are 2-4 pages in length and at the end of each chapter Wong has included a primer on a material or process symbolic of both the region and Japan’s cultural identity for example, bamboo, washi (Japanese paper), indigo dyeing and urushi (lacquerware).

Handmade in Japan would grace any bookshelf and given the resurgence of interest in hand craft techniques and Japanese culture, particularly amongst young people, its publication is timely. It takes us on a journey from long bows to lacquerware, stopping en-route to explore kites, umbrellas, candles, fishing boats, Noh masks and much more. But it is more than a guidebook. Beautifully designed and illustrated, it is a love letter from Wong to the Japanese craftspeople who are the guardians of centuries old processes, and to the artefacts which make tangible the historical, geographical and human characteristics of the Japanese archipelago.

It’s a must have for any lover of design, craft or Japanese culture and while it is not an encyclopaedic record of all Japanese crafts, it is surely one of the most accessible. My only selfish wish is that Gestalten would publish a small or digital version so that next time I am in Japan with a spare weekend I could refer to it before heading to the travel agent! In summary, to quote Wong:

‘Japanese crafts are alive and evolving, this book is a tour around the different craft regions of Japan, bringing you inside the workshops of these wonderful dedicated people.’(p. 6)

Notes

[1] In Handmade in Japan tabi are referred to as ‘Japanese slippers’ in English. The more common translation is Japanese socks. It could be these tabi are somewhere in-between these two with a structured sole. However, I decided the least controversial translation to be socks.