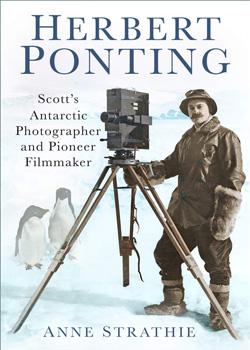

Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker

By Anne Strathie

The History Press (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-0750979016

Review by Susan Meehan

Herbert Ponting, the photographer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole (1910 to 1913), is the fascinating subject of Anne Strathie’s latest book, Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker. This completes her Antarctic trilogy. The book was due out in 2020, the 170th anniversary of Ponting’s birth but, as with many events planned for 2020, it was delayed because of Covid-19. The book is an unmatched account of Herbert Ponting’s life, the result of meticulous research.

As Strathie says, ‘Herbert Ponting created unparalleled visual records of Antarctica and of Scott’s last expedition and great scientific endeavour, a legacy which alone guarantees his place in photographic and film history’ (p. 207). Much less known, however, he also left behind thousands of evocative images of Japan, and three Japan-themed books. ‘From the advent of photography in Japan until the end of the Meiji period, he is the best photographer to have worked in that country’.[1] In 1907 he was even awarded the Imperial Order of the Precious Crown (7th class), also bestowed on other journalists who had reported on the Russo-Japanese War.

It was rather magical and somewhat incongruous to imagine Ponting regaling Captain Scott and team (29 May 1911) with a magic lantern show of Japanese gardens, temples, hot springs, volcanoes, and geisha that he’d photographed during his many travels in Japan. Scott, thoroughly captivated, went on to borrow Ponting’s recently published memoir, In Lotus-Land Japan (1910). In 1922, Strathie also tells us, Ponting’s friend, the artist Frank Beresford, gave a lantern slide lecture about his Japanese paintings to the Japan Society of London. Beresford supplemented his talk by also using some of Ponting’s slides. It so happened that Ponting had just revised In Lotus-Land Japan and took the opportunity of Beresford’s talk to present a copy to the Japan Society, another nice touch and connection for Japan Society members and enthusiasts.

Asked to describe Ponting, Strathie depicted him as an obsessive photographer, a great raconteur, a very good writer, incredibly hard working, someone who could laugh at himself, and a complicated man.[2] She certainly brings to the fore all these aspects of Ponting in her punctiliously researched biography. As well as following in his footsteps, she undertook a serious amount of archive research, and managed to locate a vast amount of Ponting’s scattered correspondence and many of his photographs.

Herbert Ponting was born in 1870, two years after the Meiji Restoration and 19 years after the Great Exhibition at which Queen Victoria discovered and was delighted by stereoscopic photographs. These were to entrance Ponting as well. Strathie is excellent at evoking the times Ponting lived in. He began work at a bank in the great port city of Liverpool in 1888, while living in Southport with his family. She mentions the increasing trade with Japan in the 1880s and Liverpool’s importance as a trading and shipping hub. Liverpool was also a world of exhibitions and artists, and at that time, following the re-opening of Japan to trade in the latter half of the 19th century, Japanese art and design had also become very popular. She also touches on the British craze for Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado from its emergence in 1885. Strathie really sets the scene for the future tug of Japan.

Ponting dreamt of going to the United States, which was the centre of photography, and in December 1892, with the financial support of his father, a well-regarded banker, he travelled by ship to post-Gold Rush California, settling near Auburn, a small town in the foothills of Sierra Nevada, California. Here he ran a fruit farm, married, had children, and seriously turned his attention to photography. Keen to realise his dream of becoming a “camera artist”, as he liked to describe himself, he began submitting photos for competitions and exhibitions with considerable success.

His first significant break came in 1900, when he was commissioned by CH Graves, a stereoview company, and by the magazine Leslie’s Weekly to travel to Asia. The stereoview company wanted to update its popular stereoviews of Japan, and the magazine wanted him to cover the Philippine-American War as well as the Boxer Rebellion in China.

Ponting felt in his element in Japan. A perfectionist himself, he appreciated the skill and perfectionism of the Japanese craftsmen he encountered, and he formed a very positive impression of the Japanese whom he regarded as extraordinarily polite, honest and very clean. He was also spellbound by Mount Fuji, which he photographed from every conceivable angle. The composition of Hiroshige’s prints – almost like stage sets – were an inspiration for Ponting’s stereoviews as were Hokusai’s A Hundred Views of Mount Fuji.

Ponting would return to Asia and Japan many times during the first ten years of his career. Underwood and Underwood, the biggest stereoview company in the world, commissioned him to return to Japan to supplement their set of Japanese photographs. He also worked as correspondent for Harper's Weekly, covering the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, and went on to travel around Japan, India, China, Korea, Java, and Burma. A skilled cameraman, he became a regular contributor to Graphic, the Illustrated London News, Pearson's and Strand Magazine.

During 1905 and 1906, he collaborated with K Ogawa, a leading Japanese photographer, to lovingly produce his books Fuji San, which contained 25 views of Mount Fuji, and Japanese Studies – comprising 52 images accompanied by captions and poetry. Both books demonstrated his flair for narrative camerawork.

Between 1909 and 1910, Ponting was incredibly busy putting the finishing touches to his Japanese memoir, In Lotus-Land Japan, while also preparing for the 1910 Japan-British exhibition at White City, Shepherd’s Bush, at which he exhibited many enlargements of his photographs.

Mission accomplished, he then turned his attention to the “Great White South”. A chance meeting led to Ponting being hired as the 1910 Terra Nova expedition’s photographer. This was Captain Scott’s second attempt to reach the South Pole.

On Antarctica, Ponting set up his own hut, complete with a dark room, and began sending the iconic photos of Scott and team, for which he is so well known, back to the UK. His images of Mount Erebus, the most southerly live volcano, and of Emperor penguin colonies, icebergs calving, and orcas presented a magnificent window onto the South Pole. After 14 months at Cape Evans, Antarctica, in February 1912 Ponting boarded the Terra Nova to sail back to the UK with more than 1,700 photographic plates. (Captain Scott would continue to the South Pole with a much reduced team of men. Strathie painstakingly tells the story of Scott’s party and how they were pipped to the Pole by Norwegian explorer, Roald Amundsen and team).

Ponting went on to spend a large amount of time on the lecture circuit, giving cinema talks of his photographs and films of Antarctica, thereby keeping alive the memory of Scott and his Polar Team. Photographs and film from his voyage to Antarctica were shown in 1962, the 50th anniversary of Scott’s arrival at the Pole. In 2012, during the Terra Nova expedition’s centenary period, Ponting’s work again became much sought after. It was featured on television programmes, in exhibitions, and in films reissued by the British Film Industry (BFI).

With little in the way of finances, all assiduously elucidated by Strathie, Ponting also had a go as an inventor, but with little success. He invented a small movie camera which he hoped would catch on, but Kodak outclassed him by bringing out a more versatile mini-projector and camera.

Strathie has done a wonderful job of bringing to our attention the life of this remarkable, restless, risk taking “camera artist” and lyrical writer. There is so much more detail to read in her masterful tome, especially with respect to his time in Antarctica, and also about the other, colourful Terra Nova expedition members. Strathie’s book made me seek out Terra Nova expedition member, Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s account, The Worst Journey in the World (1922) – the name says it all, and Beryl Bainbridge’s gripping novel based on Scott’s Polar Team, The Birthday Boys (1991).

While Strathie’s book was delayed by a year, happily, a plaque to Herbert Ponting was unveiled in Salisbury (the city of his birth) during 2020. It is great to see that his memory and legacy is once again being celebrated.

Notes

[1] Bennett, Terry, “Photographers, Judo Masters & Journalists: Herbert George Ponting, 1870-1935”, in Japan Society’s Biographical Portraits, vol. IV, part 5, pp. 303-304.

[2] Talk by Anne Strathie for the Royal Photographic Society, Wednesday, 28 April 2021 on her book Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker.