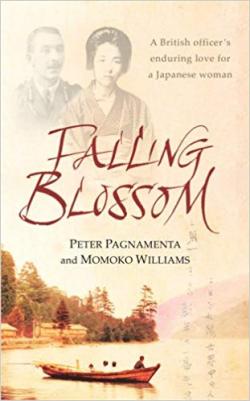

Falling Blossom: A British Officer's Enduring Love for a Japanese Woman

By Peter Pagnamenta and Momoko Williams

Century; 1st edition (2006)

ISBN 9781844138203

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

In Britain there are now many interracial marriages and the prejudices against such unions have largely disappeared especially in the case of marriages between British and Japanese. The same is largely true of enlightened circles in Japan. Where prejudices do continue they are more likely to be based on class consciousness than on racial grounds. But in the first hundred years or so after the end of the Tokugawa era there were strong objections against such unions especially among the new Japanese elite. There were, however, a number of well known and successful interracial marriages as well as some failures. One outstanding example of a successful Anglo-Japanese match was that between Baron Sannomiya Yoshitane who became Grand Master of the Ceremonies to the Imperial Household in the late Meiji period. Another was that of Mutsu Hirokichi, son of Mutsu Munemitsu, Japanese Foreign Minister, with Ethel later known as Countess Iso Mutsu. Ethel was the daughter of Hirokichi's landlord in Cambridge. His father forbade the marriage but when Hirokichi was appointed Japanese Consul in San Francisco he persuaded Ethel to join him there although they had not met for some years. They eventually married and Hirokichi became Counsellor in London responsible for Japanese participation in the Anglo-Japanese exhibition at Shepherds Bush in 1910. Some other matches, as Koyama Noboru has explained in an essay in Britain and Japan: Biographical Portraits Volume IV (Japan Library, 2002), ended in failure. Some British diplomats, officials and others in the Meiji period, such as the outstanding diplomat Sir Ernest Satow, had Japanese mistresses or common law wives which they hid from the prudish eyes of Victorians in Britain. Some others, who made their home in Japan such as Captain Frank Brinkley, insisted on marrying their Japanese mistresses. Lady Arnold, the Japanese widow of Sir Edwin Arnold, became a pillar of the Japan Society in London in the early decades of the twentieth century.

There were sadly a number of cases where there was real love and affection on both sides but which ended in unhappiness if not tragedy. These two books (the first one in the previous review - Kawada Ryokichi - Jeanie Eadie's Samurai: The Life and Times of a Meiji Entrepreneur and Agricultural Pioneer) tell two such stories, based on letters which were fortunately preserved. Both are moving accounts of tragic love affairs - some might call them tear-jerkers. In both cases the woman was the loser. It is tempting in these days when we rightly attach importance to equality of the sexes to condemn the men involved for at the very least insensitivity, but we cannot know all the circumstances and should perhaps reserve judgement.

Falling Blossom: A British Officer's Enduring Love for a Japanese Woman

Falling Blossom covers a later period than the previous book reviewed (Kawada Ryokichi - Jeanie Eadie's Samurai: The Life and Times of a Meiji Entrepreneur and Agricultural Pioneer). It traces the story of Captain Arthur Hart Synnot, DSO, a tall moustachioed veteran of the Boer War and scion of a distinguished military family from County Armagh, who was posted to Tokyo as an army language student in 1904. There he fell in love with Suzuki Masa, who was working in the Japanese officers club. Masa, whom Arthur called Dolly, was a pretty and at 26 a mature young woman, the daughter of a barber from shitamachi who had had a brief and unsuccessful marriage. The authors describe her as having 'a gentle smile, a rather modest downcast look, and a delicate almost childlike complexion.' Arthur asked Masa to become his housekeeper and she helped him with his language studies. Quite soon Arthur was sent to Manchuria where he was part of the British observer mission with the Japanese army fighting the Russians. He kept in touch with Masa writing to her on Japanese paper in his elementary Japanese. Masa kept all his letters and these provided the basis for the story of a love affair which lasted until 1918. Arthur asked her to marry him and come with him to Ireland, but she was reluctant fearing that she would not fit in or be accepted by his family. But she did agree to spend some time with Arthur when after he was posted away from Japan he managed to get a staff appointment in Hong Kong. Later he had to return to his regiment and served in Burma where he was unhappy and Masa could not join him. When the First World War broke out Arthur was serving in India where Masa would have had a difficult time with the memsahibs. Arthur perhaps inevitably felt that he should be with the army in France and in due course he found himself in the trenches. He was awarded a bar to his DSO and eventually promoted to Brigadier General. He had tried on a number of occasions to get himself appointed as Military Attache in the British Embassy in Tokyo, but perhaps because the authorities were aware of his attachment to Masa he was never successful. He looked forward instead to leaving the army when the war ended and joining Masa back in Japan, but this was not to be. In 1918 Arthur lost both of his legs in one of the final battles of the First World War. He managed to pull through and learn to get around on artificial limbs, but he was clearly daunted by the prospect of a long sea journey and wondered how in his legless state he could cope with life in Japan. So perhaps it was understandable that he decided to marry the nurse who looked after him so kindly and who would fit in more easily into his family. Masa, who had had two sons by him and who had been supported by Arthur's modest remittances, reacted furiously to Arthur's marriage. Eventually she accepted the inevitable and they continued to correspond. His younger son died early, but his elder son, who was known as Suzuki Kiyoshi and who died in Manchuria in Russian captivity in 1947, deeply resented his father's behaviour. Arthur died during the Second World War while Masa lived on into the 1960s. She had carefully kept all the letters Arthur had sent her in Japanese. He had learnt to write elegantly formed characters and had kept up his knowledge of the language despite his long periods away from Japan.

The authors have carefully researched the background to the lives of the two lovers and draw an interesting picture of life as it would have been experienced by Arthur and Masa.

The outcome for the two women, one a young Scottish girl and the other a pretty but faithful Japanese girl, was a sad one. Both stories are absorbing and well worth reading as such, but both books also throw much interesting light on social history.