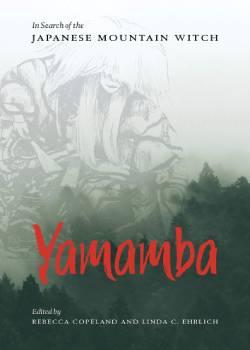

Yamamba: In Search of the Japanese Mountain Witch

Edited by Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. Ehrlich

Stone Bridge Press (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-1611720662

Review by Riyoko Shibe

The Yamamba – the mountain witch, crone, or hag, part of the widely recognised “old woman in the woods” folklore – can be traced back to the Muromachi period (1336-1573), a time of rapid population growth when merchants and villagers began to travel more frequently into the mountains. Solitary women who had moved to the mountains, driven by illness or in seek of solitude, became more visible to the wider population, inspiring stories of fear and hope as merchants met both helpful and hostile women during their travels. Tales emerged associating the Yamamba with fertility, nature, and temperamentality, from devouring men, to endowing travellers with gifts, to birthing thousands of children at once.

Through creative writing and scholarly analysis, Rebecca Copeland and Linda C. Ehrlich’s anthology examines mythologies around the Yamamba. Incorporating voices from Japan and the USA, the anthology shows how the Yamamba, ‘less constrained by the tradition, customs, and social norms expected for a woman’, reflects not just disgust and rejection of women who dismissed these expectations, but also shows how these women enacted agency in their rebellion of these norms. The Yamamba is thus located in old and new folktales, as well as in real-life manifestations such as in the gyaru subculture of the 1990s.

One example of the Yamamba explored in the anthology is the Noh play, Yamamba, written in the 1400s. Ann Sherif interviews the Noh performers Uzawa Hisa and Uzawa Hikaru, who bring the depth, physicality, and contradictions of the Yamamba to the fore. Hisa recalls during her lessons that she was taught ‘that the yamamba embodies an unimaginable amount of energy … it should be like a mountain moving … The performer has to conceive of that level of strength and energy’.

Underlying the book is the notion that the Yamamba’s sex must be “female”, given her associations with fertility, her unconventional lifestyle and rejection of typical beauty, and connection with nature, delusion and attachment. Echoing this, Hisa reflects that ‘if the yamamba were a man, it would be a very boring play … [lacking] in the scale or weight implicit in the demon role’.

In the interview, the discussion hints towards broader commentary on gender fluidity, adding a new dimension to discourse around the Yamamba’s gender. Sherif probes the Noh performers on their viewpoints on twenty-first century perspectives on the topic, and they observe that performers of Yamamba do not perform her as a woman. Hisa states that ‘what is important is where the energy comes from, not who the character is’, and so, ‘when we perform Yamamba, we don’t think of it as performing woman … The performer can’t conceive of it that way’.

However, the discussion does not move beyond this, and the question remains: how does the Yamamba fit into twenty-first century – and historical – conceptions of gender? A complementary chapter would be welcome, perhaps exploring how the Yamamba’s sex and gender have come to be understood, and how gender is challenged, or reinforced, by these manifestations. Without such chapters examining themes brought up in interviews and short stories, the anthology remains slightly unbalanced, romanticising the Yamamba, her mythologies, and the discourses which surround her.

A similar critique can be made of Laura Miller’s chapter, ‘In A Yamamba’s Shrinebox’, which briefly touches on how the mythology manifested in the kogyaru or gyaru subculture and fashion trend of the 1990s. Young women who challenged mainstream beauty norms were nicknamed Yamamba for their appearance: they wore short skirts and bleached their hair, while their makeup consisted of bright eyeshadow and lipstick, with white paint around the eyes and mouth emphasising deep tans from tanning salons and creams. Thus, we learn that while Yamamba was used as an insult, the use of the word shows both how women rejected gender expectations by embracing alternative fashion and makeup trends, and also how they were rejected from society for this style, suffering abuse from men repulsed by their image.

Contention appears when Miller describes the process of fake tanning: emulating Black American culture, and also driven by their wish to reject Japanese beauty norms, gyaru darkened their skin through intensive tanning. The colourism and racism of this practice is not mentioned and appears to be actively sidestepped, with Miller translating the nickname derived from skin darkening, ganguro, as ‘face black’, rather than the more common translation of ‘blackface’. With dark-skinned and/or mixed-race Japanese people suffering harassment and discrimination, darkening one’s skin through a perverse appropriation of “coolness” can only be looked on critically. Failure to mention this context builds an uncritical, over-romanticisation of the Yamamba mythology, and also feels outdated given the plethora of literature and cultural commentary on the practice of blackface in gyaru culture.

A final critique would be David Holloway’s short story on Aokigahara, suicide and the Yamamba. To K, a student in Japanese Studies, ‘the Japanese just seemed comfortable with suicide’, and inspired by ‘the legacy of seppuku on the battlefields during the middle ages’, K sets out to Aokigahara to kill himself, only to be saved, in some sort of way, by an encounter with the Yamamba. It is unclear what the story brings to the anthology beyond reinforcing outdated tropes tying suicide to a Japanese historical legacy and an innate Japanese sensibility. While it seems that links are being drawn with an ancient mythology and a newer ‘flashpoint of curiosity and controversy’, Aokigahara, the chapter nonetheless comes at odds to the other contributions, as the relevance of the Yamamba, aside from the general relationship with forests and nature, is unclear.

Without venturing beyond an introduction to the mythology itself, the anthology remains at a slightly superficial level: more in-depth analysis could complement the interviews and creative writing pieces, while commentary could have included more references to wider literature on the subject. Despite this, the anthology is a creative exploration and rich introduction to key texts and artists exploring the Yamamba.