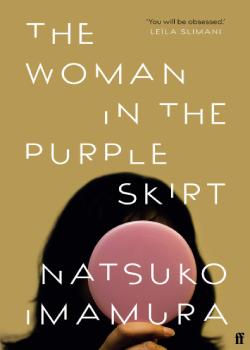

The Woman in the Purple Skirt

By Imamura Natsuko

Translated by Lucy North

Faber & Faber (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-0571364671

Review by Cameron Bassindale

Winner of the prestigious Akutagawa Prize, one of Japan’s highest literary honor, Imamura Natsuko is the latest in a growing list of contemporary female authors to be introduced to the British literary scene. She is certainly in good company. The likes of Kawakami Hiromi, Banana Yoshimoto and Murata Sayaka are now readily available in chain bookstores up and down the UK. What's more, this wave of Japanese female voices being translated into English seem to touch on similar experiences: social alienation, workplace pressures and the threat of sexual violence. In The Woman in the Purple Skirt, Imamura adds her own take on these themes through a narrative with a gripping conceit and satisfying ending.

At its core, The Woman in the Purple Skirt is a story about a woman who stalks her neighbour, in the hopes of striking up a friendship with her. As the story progresses however, the reader’s attention naturally shifts from the eponymous character to the narrator, who calls herself ‘the woman in the yellow cardigan’. What starts off innocently enough does take on a rather more sinister tone as the novel builds up to its conclusion. The narrator's descriptions of waiting for the ‘woman in the purple skirt’ in dark alleys or by a bus stop go quickly from eliciting sympathy for a woman trying to make a friend in the digital age to a sense of deep foreboding. However, Imamura stops well short of making this novel a grizzly psycho-thriller, as perhaps a lesser author may have been tempted to do. To my mind this is what makes the ending so satisfying; I found myself imagining any number of ways the novel may finish only to be pleasantly surprised Imamura steered well clear of tropes and cliche.

The descriptions of workplaces, and women’s role within them in modern Japan, is another area which Imamura manages to provide novel views. The Woman in the Purple Skirt at times has shades of Murata Sayaka’s excellent Convenience Store Woman, a novel whose protagonist is obsessed with the din of her 24/7 convenience store chain. For Imamura, the narrator’s obsession is with a female colleague. For both novels, the result is the same; a narrative which dissects the intersection between femininity and the modern workplace. In fact, ‘the woman in the purple skirt’ does not begin working at the hotel with the ‘woman in the yellow cardigan’ until she finally reads a subtly placed newspaper advert meant for her to see. Before she joins the hotel workforce, the narrative voice is rather harsh on her moving from job to job, unable to pin down a career. The distance between the two characters, and the narrator's irritation at ‘the woman in the purple skirt’’s work ethic helps build the atmosphere of modern work in Japan, which is often gruelling and worse for those who don’t conform.

Once she begins work at the hotel, the dangers of non-conformity become more prescient. Imamura has some stellar lines of dialogue laced throughout the scenes at the hotel, between the supervisors and the regular staff members. For example, at one point the narrator overhears a supervisor ask the new recruit ‘Hino-chan. Is there a reason you don't use the hotel shampoo?’. For me this is a masterful line of dialogue, which represents the pressure to conform within the workplace, compounded by the pressures modern Japanese women face with regards to their body. As the novel goes on, the narrator begins to hear rumours about ‘Hino’ being given favourable treatment because of an alleged affair. From then on, the staff totally turn against her, taking every opportunity to criticise her work and character. Imamura weaves into the narrative here a subtle class commentary. At the start of her employment she was encouraged, off the books, to help herself to food and drink when she was carrying out her duties. As her colleagues begin to take a dislike to her, they out her for doing just that. In so doing, Imamura perhaps is trying to paint a picture of a lack of solidarity between working-class Japanese.

So too does Imamura frame in an interesting way another problem that women face: sexual violence. Hino’s experience on a bus, in which a stranger gropes her from behind, is all too common in modern Japan. What makes Imamura’s description unique is the way in which it is framed, from the viewpoint of a female stalker. The narrator sees the situation as an opportunity to touch her, as the fracas on the bus occurs, she reaches her hand out through the crowd to ‘tweak her nose’. This moment is the tipping point in the novel, where it transitions from strange to outright bizarre. Given the pacing of the novel, which is lively and doesn’t rest in one place too long, this makes for a quick build-up toward a truly well-thought-out ending.

With her finger clearly on the pulse of Japanese literary modernity, Imamura Natsuko’s The Woman in the Purple Skirt manages to touch on issues surrounding working-class women in Japan while managing to maintain a unique writing voice within an even more unique story. The result is a thoroughly readable book, well deserving of its place in the contemporary Japanese canon.