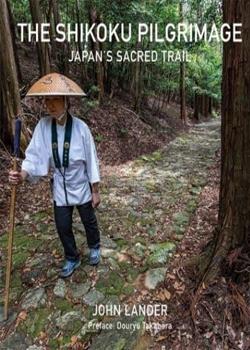

The Shikoku Pilgrimage: Japan’s Sacred Trail

By John Lander

River Books (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-6164510517

Review by Jess Cope

For most pilgrims on the 1142km Shikoku pilgrimage, a journey taking in 88 temples around the Shikoku Island, the smallest of Japan’s four main islands, the 12th temple, Shosan-ji, is the first nansho – dangerous and hard to reach place – that they will encounter. Accessible by car via a road that gently winds up the Akui river valley, there is a hair-raisingly narrow final ascent that climbs in short order from 200m up to the temple’s location some 700 meters up in the mountains. Those attempting the pilgrimage on foot generally opt for a more direct route, albeit one that takes them over three mountain ridges, requiring almost 1400 meters of cumulative ascent and 700 meters of descent to reach the temple. All pilgrims will thus likely be relieved to finally reach the temple’s impressive ancient wooden sanmon (front gate), behind which immense Japanese cedars rise from the white gravel of its compound, the wooded slopes of the mountain falling away in the near-distance. The kanji characters for “Shosan-ji” - 「焼山寺」 - mean “Burning Mountain Temple”, hinting at the 1,200 year old legend associated with the temple, in which a young monk sealed away a fire-breathing dragon who had terrorised local villagers and set the mountain ablaze. The monk was Kobo Daishi (774-825), also known as Kukai, who would go on to found Shingon Buddhism and whose journey around Shikoku conducting ascetic training in the 9th century has been traced by innumerable pilgrims over the centuries since.

The legend, one of many associated with Kobo Daishi, is outlined alongside a gorgeous photo of Shosan-ji’s sanmon (p. 63) in John Lander’s new book The Shikoku Pilgrimage: Japan’s Sacred Trail. The book opens with a short background on some of the key elements making up the pilgrimage, including basic temple protocol, the traditional pilgrimage clothing, and a potted history of Kobo Daishi himself. It also covers the unique cultural practice in Shikoku of o-settai (p. 15), whereby local people give gifts to pilgrims (known as henro or with the honorific ohenro) as a means of vicarious participation in the pilgrimage. But the main focus of the book is very much on the 88 temples, each of which is featured with a short paragraph discussing its history, legend and characteristics alongside 1-3 beautifully shot photographs.

The subject matter lends itself well to a photographic examination. The temples provide a stunning selection of ancient compounds, historic architecture, imposing Buddhist statuary, unusual gardens, and breath-taking backdrops. The book’s sections align with the pilgrimage’s four dojo (stages of ascetic training) that follow the boundaries of Shikoku’s four prefectures, and a brief introduction to the prefectures themselves leads each section. The curious reader will undoubtedly appreciate getting to know more about a frequently overlooked corner of Japan with fascinating destinations far from the well-trod tourist trails.

To those who have never heard of, much less contemplated undertaking, the Shikoku pilgrimage, Lander’s book serves as a lovely introduction. Anyone moved to visit Shikoku as a result will also find it a helpful companion, with Lander pointing out features that can be surprisingly easy to overlook. The beautiful, sculpted garden hidden behind the main hall of Temple 68, Jinne-in (p. 192), will have been missed by a great many pilgrims even over repeated visits. Similarly, the only reason that this reviewer was familiar with the stone garden at Temple 86, Shido-ji – originally designed in the 15th century to evoke ink wash paintings of Chinese landscapes (pp. 223-225) – was because of a chance tip-off from a gardener in the main grounds. Such guidance can elevate the experience, as many of the temples have unique features or customs associated with them (such as laying coins on each of the stairs of Temple 23, Yakuo-ji, p. 84) the significance of which is easy for visitors to miss.

That said, this is not a guidebook and should not be treated as such. Lander’s objective seems to be to create a visually attractive overall impression of the temples, rather than necessarily to fully capture the unique charms of each one. In this respect it is extremely successful – the book is beautifully presented, with a wonderful and diverse selection of photographs of temple architecture, gardens, scenery, ornamentation and statuary. The cumulative effect provides a balance of overview and detail to give a reasonable impression of the sights a pilgrim will encounter in the temples. Many of the gorgeous pictures perfectly capture the atmosphere of the featured temple. The uneven stony compound of Temple 14, Joraku-ji (p. 67), is instantly recognisable, as are the faded colours of the hangings adorning the threadbare Temple 22, Byodo-ji (p. 80-81). The beautiful temple wings adjoining the courtyard of Temple 64, Maegami-ji (p. 181), are well-shown.

Some temples do feel short-changed, however. Temple 49, Jodo-ji (p. 156), is represented only by a photo of two fairly unremarkable statues. There are no photos at all of the modern redesign of Temple 61, Kouon-ji (p. 178), whose altars are encased high within a jarring but remarkable piece of 1970s Buddhism-meets-Brutalism architecture. Readers familiar with the temples may therefore disagree with some editorial decisions about which photos to showcase, something which Lander himself recognises as a possibility in the introduction to the book.

But such decisions must have been extremely difficult: after all, to truly capture some of these stunning temples in full one would need to show the approach and the temple’s profile from afar, its monumental sanmon, its compound (with details of its key monuments, treasures, statuary, and garden features), its halls of worship (both inside and out), and its views. With 88 temples to cover, a book that attempted to do this for each would be impractically immense and near unreadable. With such a wealth of options to choose from, it is unsurprising that even where attractive and representative photos have been chosen, some other temple highlights have unavoidably been left on the cutting room floor.

Of course, there is more to the pilgrimage than the temples. Despite the cover featuring a traditionally dressed pilgrim, the book does not focus on the henro pilgrims themselves. Though some brief henro profiles help break up the book in the middle, henro are conspicuously absent from most of the photographs of temples. This is quite a departure from the experience of visiting Shikoku, where the henro are everywhere in their distinctive white garb – walking along the roadside, spilling off coaches in temple parking lots, lighting incense and candles, and chanting the sutras in front of the temple halls.

The journey that ties the 88 temples together into a pilgrimage is also hard to discern. Many of the temples on the pilgrimage were established during the Heian period (794-1185), when the trend of sangaku Buddhism took hold and there was an emphasis on establishing temples in remote and hard to reach places as a means of ascetic practice to cultivate almost “magical” powers (the myths and legends attached to many of the temples no doubt also reflect this trend). The pilgrimage is therefore mountainous as well as lengthy - by some calculations it features almost 25,000 meters of cumulative climbing (and thus descending) when completed on foot. As a result, pilgrims traverse a range of spectacular landscapes: the densely forested paths up to many a mountain temple, the dramatic road sandwiched between the cliffs and the pounding Pacific Ocean leading to the very tip of Cape Muroto, the charming narrow country lanes leading to the tip of Cape Ashizuri, the two temples on twin mountainous peninsulas jutting into the Inland Sea to the northeast of Takamatsu. Such sights, intrinsic to the pilgrimage, do not come through in the book.

Again, these omissions are likely deliberate, or at least conscious: the pilgrimage is too immense for a comprehensive record to be practical, and the book’s editorial focus yields its own rewards. Furthermore, such a wide range of photos would likely overwhelm many readers, and as a result the disciplined focus of the book is eminently accessible, with no prior interest in the pilgrimage, Buddhism or even Japan required to enjoy what it has to offer.

In the introduction to the book, Lander states that the photos were taken through repeated visits to Shikoku over many years. Some of the more idiosyncratic photo choices reflect that the book is a labour of love, and Lander’s affection for Shikoku and its pilgrimage shines through. The only real way to experience the pilgrimage in its entirety is, of course, to complete it in person. To the extent that Lander’s beautiful passion project inspires more people to do just that, it will have been a success.

Talk Video - One Step at a Time: Exploring the Shikoku Pilgrimage

Watch the recording of our online lecture with author John Lander on Saturday 25 September 2021 when he took us on a journey along the Shikoku Pilgrimage guiding us through the evocative images and stories he has been documenting for his latest publication The Shikoku Pilgrimage: Japan’s Sacred Trail.