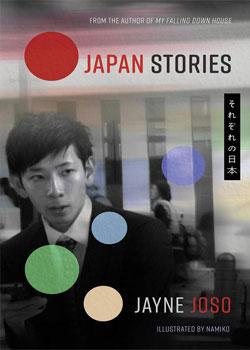

Japan Stories

By Jayne Joso

Seren (2021)

ISBN-13: 978-1781725894

Review by Eleonora Faina

Japan Stories is a collection of short fictions by Jayne Joso, some of which gracefully illustrated by Japanese Manga artist NAMIKO. All these stories revolve around the main characters’ loneliness taking many shapes and forms, often accompanied by trauma, emotional detachment, shame, and contempt towards “normal” people. Those who manage to function and connect in the society are mostly mocked, but also envied. That is because all main characters are outcasts to some degree, few of them (Oona, Chizuru, Bowie) shaped after Joso’s real acquaintances.

Far from being a light-hearted read, Japan Stories’ succinct format is quite perfect to engage with these stories effectively; the latest section of the book called ‘The Miniatures’ presents even shorter, haiku-like features. It must have been a long time coming for Joso’s latest work to come to life; despite claiming she never intended to write with a theme in mind she still birthed a peculiar cohesive piece of modern literature in one go.

Her influence as a writer and her fascination with Japan is strongly connected to Angela Carter’s work, specifically Fireworks, a selection of short stories Carter wrote whilst she was living in Tokyo. Carter’s poetic activity combined to a deep appreciation for haiku and the work of Lydia Davis highly influenced Joso’s choice of short format for this publication, exercising brevity as a form of control over her imaginary world.

Interestingly, in her past work Joso’s approach to Japanese culture has been somehow reverential by wanting to translate it to the Western public as accurately as possible. My Falling Down House - another Seren-published book taking place in Japan and winner of The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation Award- was written on those bases. This publication though, follows a different approach. This time Joso is allowing herself to be “mischievous” in telling darker and more complex stories, distancing herself from her past naturalistic work. Freer to stretch her imaginary legs and to take more room for exploration she proceeds to tell us tales of solitude within the modern Japanese society by engaging with new sharper formats and Carterian gothic surrealist elements. The emphasis is put on the characters’ internal world rather than their external realities, blurring the line between reality and fantasy and how much the tales we tell ourselves influence and shape the world surrounding us.

Love and the ideas surrounding love are recurring themes throughout the second-half of the book, yet still accompanied by a high degree of loneliness. Shoei’s story it is one of the longest and possibly the first “real” love-story we encounter. It is a misunderstanding tragedy of idealisation between him and Grace, clashing on cultural grounds and expectations towards what is the meaning of their relationship. Shoei would be happier with a ‘shallower, less unsettling’ love and regards his time with Grace as if it was from a movie, as ‘fiction’ before his real life starts. This time solitude embraces two people falling in love.

The stories of Mr Yoneyama and Mr Takahashi explore broken families from different perspectives, cleverly mirroring the solitude of modern men. The first is an unwilling stranger to his wife and children; for some unknown reason he is unable to manifest or communicate his needs despite his yearning for connection with his loved ones. Those conflictual feelings are portrayed as raw and heart-rendering to the reader. On the other hand, Mr Takahashi is highly detached from reality as he perceives himself as a good husband and father mainly because he represents the household breadwinner. Yet, he is oblivious of what his wife and kids are up to these days and not particularly interested in finding out while he engages in extramarital affairs. The turning point in Mr Takahashi introspective journey is the encounter with his new American colleague, who he starts spending more and more time with, showcasing an “oddly” close relationship with his family and unshakable marital values. The comparison highlights to both the readers and to the main character how lonely Mr Takahashi truly is in his life, the shallowness of his character and the weightlessness of his relationships and status.

Joso’s writing style is perfect to describe these themes, her sentences often repeating, mimicking the natural train of thoughts of an obsessive mind. Her ability to shapeshift into a diverse deck of characters with different communication abilities and traumas is remarkable. The language is predominantly descriptive, and some stories are quite cryptic and need several reads to come to life and solve the puzzle Joso puts in front of you. All stories present degrees of realism but from time to time they can take a magical tangent, sprinkling elements of the extraordinary in an ordinary and, at times, alienating Japanese life.

Misaki’s story perfectly encapsulates this by describing a young woman’s sense of self-sufficiency, purposely alienating others her entire life, escaping societal pressure and social conventions. Her nihilist nature despises the ‘act of being human’ and regards socialising as a farse. She embarks on an apparently random quest of building a tower – representing both a mean of isolation and connection – by herself in the neighbourhood she lives in, whilst the pandemic dictates social distancing. Surprised and amused by her neighbours’ acts of kindness alongside morbid curiosity for her strange pursuit, the story suddenly assumes supernatural tones.

Joso’s use and characterisation of physical spaces here transcends its mere structural form. Describing herself as a solitary child who put lots of effort in curating what inhabited her room and her surroundings, [1] her deliberate approach to structural descriptions in Japan Stories instantly assumes a deeper meaning. This tendency manifests in her depictions of Japanese houses, living organisms subject to transformation by taking different shapes using shoji (sliding doors)- possibly translating as a metaphor of human behaviour. Chizuru’s story is representative of this, her house a reflection of her internal world, regulated by unbreakable rules. The central room does not match the traditional style of the entire house and is completely covered in cellophane, to protect (or to separate) what is most precious to this landlady character.

Arguably, not only the Japanese society but also Western ones are experiencing a collective generational solitude due to a widespread sense of instability (job-related, market-related, and consequentially life-related). In Japan this has been historically present and – to a point – inherited in a low birth rate society where long-working hours, sense of duty and status are the pillars of one’s self-identity. As we also seem to live in a culture nudging us to cast aside negative emotions – or avoiding their exploration and meaning as much as possible – this further pushes individuals to be not only disconnected to others, but mostly to themselves.

This solitude is familiar and transcends cultures, and here that is where the true power of this book lies. Open to interpretation, it could be read as a critique to the Japanese society, an analysis of similes in Western and Eastern social matrixes and its elements of alienation, but also as a love letter to a country where Joso spent several years of her life, honouring with every description its architecture and rituals.

This book could be easily read in one go, but I refrain you to do so. Some stories are quite heart-breaking, a few might require a re-read to be decrypted and others may event haunt your mind, demanding time to be fully digested. Overall, representing a good first approach to Joso’s work, Japan Stories allows the reader to savour her distinctive style in small, deliciously bitter bites.

Notes

[1] Interview with the Author’s Club on YouTube.