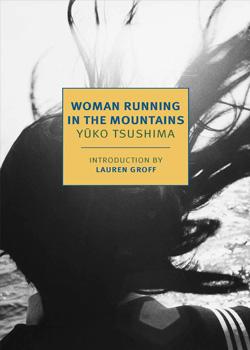

Woman Running in the Mountains

By Tsushima Yuko

Translated by Geraldine Harcourt

The New York Review of Books (2022)

ISBN-13: 978-1681375977

Review by Laurence Green

In a world where the daily cycle of new media seems to march at an ever quicker pace, a parallel path has begun to open, one which offers something new, by way of something old - the ‘re-discovery’. Films, books or albums lost to time the first go around, or perhaps simply ripe for new appraisal. When the stars align in just the right manner, these fresh opportunities for old works to shine can go so far as to shift our understanding of pre-conceived historical narratives of a body of work. New names rise to the fore of the discourse, and our contemporary understanding of a canon we thought we knew so well - ‘Japanese Literature’ - thrums with the tantalising pulse of something that feels like it has been biding its time until this precise moment. Now uncorked and set free, we can’t get enough of it. Yuko Tsushima (1947-2016) - youngest daughter of famed writer Osamu Dazai, who committed suicide when she was only a year old - is perhaps, one such author.

Following on from the immensely encouraging success of handsome re-releases by Penguin Modern Classics of Tsushima’s previous works Territory of Light and Child of Fortune, The New York Review of Books’ edition of Woman Running in the Mountains - originally published in Japanese in 1980 - is simultaneously a novel that you could recommend to a first time reader of Japanese literature, and to a seasoned longtime lover who feels they’ve read everything there is to offer from those works available in English translation. As with the above-mentioned previous works from Tsushima, Woman Running in the Mountains is ably translated once again by Geraldine Harcourt (who sadly passed away in 2019).

Our protagonist this time around is Odaka Takiko; pregnant as a result of a brief affair with a married man, she is now a source of sorrow and shame to her abusive parents. For Takiko however, the child represents opportunity - something wholly her own, and a route to a new sense of meaning and direction in her life, no matter how challenging that path might be. Focused tightly around a central theme of maternity, Takiko’s pregnancy, the experience of giving birth, and then of motherhood itself, are spelled out in granular detail here. Hard reality confronts her at every turn, her status as a single mother serving as a foundational stigma that all else stems from - not least the grating relationship with her judgmental mother. The novel’s early movements focus on Takiko’s stress in securing a place for her child in a nursery - the staff inform her that many mothers will put their names down on waiting lists as soon as they discover they are pregnant, such is the intense demand for places.

Some of what we hear can be shocking - particularly to 21st century sensibilities. An informative footnote a third of the way into the book tells us of the distinction in Japanese family registers between a child being registered as ‘male’ instead of ‘first son’, a status distinguishing illegitimate from legitimate children. Copies of the family register are required for official procedures such as school enrollments and job applications; as such, Japan has a very low illegitimacy rate - 0.8% at the time the novel was written in 1980, compared to 18.4 in the United States. Later segments of the novel take on an almost diary-like feel, the passing days chopped up into segments punctuated by the baby’s bodily functions: ‘7:00 - Began to cry. 7:15 - Formula (180cc). Crying louder. 8:30 - To sleep. Woke up right away and yelled’. The pace is relentless, the demands never-ending. Takiko must endure.

Crucially however, and somewhat at odds with many contemporary literary authors writing on similar themes today, the tone is never vitriolic in nature. There is very little hate, regret or frustration to be found in these pages - only a coolly dispassionate observance of the act of motherhood and its implications for a woman. The novel feels both incredibly prescient in its ability to resonate with later waves of feminist literature - eg. Mieko Kawakami’s Breasts and Eggs - but also feels like it is part of a trajectory belonging solely to Tsushima alone.

There are some interesting translation idiosyncrasies, that given a more contemporary style, one feels might have been handled differently. We often hear of ‘arrowroot jellies’, which no doubt would have been left simply as kuzumochi now. Harcourt’s translation in fact dates back to 1991, and it is striking to think that 30 years on, we are now as far away from the world of the novel as the 1950s or 60s would have seemed to those living through the 80s and 90s. Harcourt’s translation - at once at a remove from both past and present - achieves a particularly lucid quality, emphasising the artistic cleanliness of Tsushima’s prose all the more. The life of the protagonist might be a particular kind of mundane everyday experience - but there is incredible beauty to be found in this simplicity.

This edition is appended by an introduction from Lauren Groff - who will be familiar to many as the author of the popular novel Fates and Furies. Her insightful preface tells us of Tsushima’s place within the Japanese literary tradition of the I-Novel; a form of autofiction that bears some similarity with the Western school of literary naturalism and came to hold particular allure with Japanese audiences through the course of the 20th century. Both through its extreme realism, and its unique access to the psychological states of its characters, the I-Novel’s bewitching charms are self-evident in its blending of almost documentary-like observational qualities with a kind of hyper-intensity offered by the placement of the narrative voice firmly within the central ‘I’. It is not merely that we come to see the world through their eyes, rather, we take on and embody every aspect of their lived existence, through to the smallest detail.

The greatest testament to Tsushima’s power as a writer is that her work is uniquely balanced between cleanly palatable accessibility, and an aesthetic sense that feels almost as if it belongs in a stark contemporary art gallery. Woman Running in the Mountains is at once both literary and incredibly literal in its ability to paint with words the kinds of world we all inhabit from minute to minute, hour to hour. In every cluttered urban edifice, in every baby’s cry, in every trickle of sweat; a realm of possibilities.