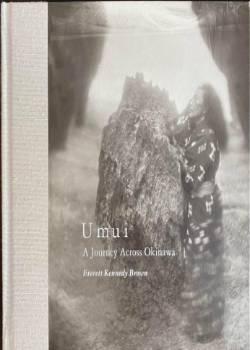

Umui: A Journey Across Okinawa

By Everett Kennedy Brown

Salone Fontana (2022)

ISBN: 978-4909860538

Review by Renae Lucas-Hall

‘Umui is the soul of the Okinawan people. It is born from the ocean, land and sky and nourished in their music, dance and daily life.’ (P. 2)

Everett Kennedy Brown is an American photographic artist, writer, and film producer and long term resident of Japan. His work has been featured in The New York Times, Le Monde, on CNN, NHK and is in permanent collections in Japan, Europe, and the United States. He has also been awarded the Japanese Government’s Cultural Affairs Agency Commissioner’s Award in recognition of his creative activities and his book was nominated and shortlisted for the Tadahiko Hayashi Award.

He uses the wet-collodion process to capture landscapes and cultural aspects of Japan. The collodion wet plate process was invented in 1851 by an Englishman, Frederick Scott Archer. It is a complicated method of photography which uses a large format camera on a tripod and a portable dark black room tent. The exposures are long, meaning the camera lens stays open much longer than an instant and the subject needs to pose perfectly still for several seconds or more so as not to distort the outcome. Brown can only take one photo at a time and he makes a glass negative on site using a highly flammable liquid gel. The results are extraordinary. He uses Japanese pottery and ink brush techniques to add his own personal touches to the glass plates (cut at the end) to create fascinating images which look like they were produced in a bygone era.

In this book, titled Umui, emphasis is on the unseen world that animates Okinawa. Brown’s first photograph on the front cover is an Okinawan woman in traditional dress leaning into a protuberant holy rock. She is standing with her eyes closed, deep in thought or prayer. This natural stone mass proudly sits in a cove at a sacred utaki a place where the noro (female shamans) come to pray.

From here, Brown makes his way to Kudaka, the most sacred of the Okinawan islands. According to legend this is the gateway to Niruyakanaya, the heavenly kingdom beyond the horizon. The shadows and contrasts in the photo taken here draw the eye towards this vanishing point where the sea blends with the sky. The ocean looks settled and inviting as if it is guiding the onlooker towards the home of the gods.

A wonderful example of Brown’s ability to take a contemporary picture that looks like it is one hundred years old is the photo of the traditional Okinawan lady on page 12. She is dressed to perform a sacred dance but she is sitting beside the trunk of a twisted pine tree with flowers in her hair. Her face is composed and a feather-like shadow, caused by a chemical stain, is escaping from her gentle hands as if she were awakened by a celestial nymph guiding her towards an enlightened state. A similar smoky silhouette extends from the conch shell horns blown by two local men in the photo opposite. After this picture was developed, there was another mysterious chemical stain that looks like a dragon’s tail.

‘If there is no umui, then beauty is empty . . . without umui, all knowledge is contrived and meaningless.’ (p. 14)

Brown was impressed by the essence of the Okinawan people. He would look deeply into their eyes as he photographed them. He was always in search of that enigmatic umui quality only the Okinawan people seem to truly understand.

‘Umui is often understood as “thoughts” but the meaning is closer to the prayers and emotions that well up in the heart… The women had explained to me that when they go into prayer, they enter a kind of heightened awareness, not unlike the Aboriginal Dreamtime, where they come into contact with their ancestors from the past and have glimpses of the future.’ (p. 14 & 18).

The photographs of the five ladies on the beach in white robes on pages 21, 23 and 90 are marvellous. It feels as though one is hiding behind a tree watching a secret ritual not open to the public. They are in a trance-like state, completely unaware of the present. These photos capture the fine line between this world and the spirit land.

The next photo of Brown’s friend in the sea is slightly different to all of the others. He accompanied his Japanese companion to the southern end of the island to a place called Yamakawa Utaki where the goddess of creation, Amamikyo, arrived after her first landing at Kudaka Island. When Brown took a photo of his friend in the shallows, he accidentally dropped the glass plate, smashing one part into small pieces. But he decided to salvage the broken image. The cracks in this photo are the reason it is unique and a wonderful example of the Japanese concept of mono no aware or the fragility of life. The resurrection of this piece is similar to the way a potter uses kintsugi or golden joinery to repair a broken ceramic. The philosophies are the same. There is beauty in the broken. One must embrace the transience in life, or wabi-sabi.

After that bathing ritual, the two men head into a dark forest to a utaki where legend says Amamikyo set up temporary residence. It is a place Brown felt an inordinate sense of peace and tranquillity and the true presence of umui.

History and culture are evident throughout this book. Brown explains on page 44 how the noro shaman in Okinawa were considered superior and more powerful than any military force. These noro used to pray at an old castle called Katsuren-jo. The Okinawans believe the supremacy of the noro allowed them to welcome envoys here from other countries and parts of Japan with open arms, fine food, music, and dance. Brown’s photo of the stairs leading up to this place of worship is transcendental. The crack in the middle suggests caution but the clouds above seem so alluring.

For Brown, Okinawan faces are cosmopolitan. Through the centuries, people as far away as India, Europe, and South-East Asia have made their way to Okinawa and stayed. The face of the true Okinawan is now a hybrid or combination of many lands. The photo of the Okinawa man on page 51 is a blend of various cultures with wise but amicable characteristics.

Brown’s photographic journal is also a wonderful commentary on Japanese traditions. Like the rest of Japan, the Obon festival is a yearly celebration of the dead which takes place between August and September. In Okinawa, dances are performed with masks which are jovial and friendly, reminding the islanders of their ancestors. Brown’s photos of these masked performers on pages 62 and 63 are mystical and enchanting.

Past traditions which have lapsed over time are now being revived in Okinawa and it is encouraging to see this photographer documenting this resurgence in cultural identification. Brown shows his appreciation for young artisans who are creating new fabrics using traditional banana fibre cloth. He also mentions and photographs an entertainer known as Kyotaro who dresses in outlandish clothes. He can be seen at their festivals and funerals chanting Buddhist prayers. The photo of Kyotaro on page 71 is utterly charming. Brown has captured his infectious smile and twinkling eyes with an evolved sense of sincerity.

Brown’s glass plate images in this book leave a profound impression of what it means to be Okinawan and his text draws attention to the values and beliefs that influence their lives. When he meets an old potter in the traditional pottery district of Yachimun in downtown Naha, Brown is reminded of the Okinawan phrase “nuchi du takara” which tells us that life is more important than material possessions. Brown’s photo of this potter drinking awamori, the local rice spirit, and sitting with his family on page 75 prompts us to appreciate life and to consider its brevity.

Brown’s final image on page 79 evokes feelings of intimacy and a tender appreciation of nature. A rock wall in the shape of a love heart at a utaki at the southern end of the island appears like another gateway to the heavens. There is a little swirl of a chemical stain in the top right-hand corner of the image which looks like the gods are in the distance observing us but they’re not too far away to touch our souls.

During his interview with Japanology Plus which aired on NHK, Brown said ‘Japan for me is a long, ongoing and ever-deepening love affair. This country has offered me so much beauty, so many wonderful aesthetic experiences, and this journey is just forever continuing’. Brown’s photos are stunning, timeless, and ethereal. One can only hope his words ring true so we can carry on our appreciation of his unique photographic process with more collections which capture a country offering us so much in return.