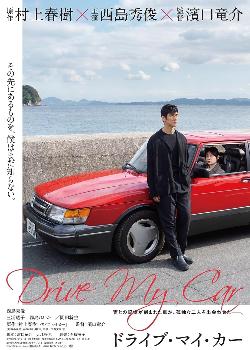

Drive My Car

Directed by Hamaguchi Ryusuke

Cast: Nishijima Hidetoshi, Miura Toko, Okada Masaki

Official website (2021)

Review by Michael Tsang

Whether you like Hamaguchi Ryusuke’s 2021 Oscar-winning Drive My Car or not, you at least have to give him credit for expanding Murakami Haruki’s source text – a short story of a few pages – into a three-hour full feature film. This augmentation allows Hamaguchi to reinterpret Murakami’s story with a different depth and world view, exploring new themes absent in Murakami’s version.

Theatre director Kafuku is invited to Hiroshima (note the symbolism of this setting) to direct a multinational, multilingual production of Anton Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya. He is required to allow the theatre’s designated driver, a young woman named Misaki, to escort him off and to work. The driver and the passenger begin to reveal their stories, with Kafuku reflecting on his wife’s affairs and then death, and Misaki slowly disclosing her upbringing. Meanwhile, as it turns out, the actor called Takatsuki who plays the male lead in Kafuku’s production was one of the men with whom the wife had an affair. When this male lead gets himself into another trouble, Kafuku had no choice but to play the title role himself.

Veteran actor Nishijima Hidetoshi (as Kafuku) and popular actors Miura Toko (as Misaki) and Okada Masaki (as Takatsuki) all deliver more than competent performances, but the international cast of the Uncle Vanya performance also stole the show. Nishijima’s looks always have a tinge of melancholy and is impeccably cut out for the role of Kafuku. Miura captures Misaki’s blunt and slightly awkward personality with precision. Meanwhile, Okada’s own commercial success parallels his character in the film who is also a popular actor, and he portrays Takatsuki’s impetuousness well.

One main difference between Murakami’s textual version and Hamaguchi’s filmic version is scale. Whereas Murakami’s original story mainly explores heterosexual relationships, Hamaguchi’s scales up the story to explore national and international traumas that Japan is involved. The change in setting from Murakami’s Tokyo to Hamaguchi’s Hiroshima is obvious; so is the change from Murakami’s yellow Saab to Hamaguchi’s red. Red – as in the red dot on the flag of Japan. Therefore, the film can be read on an allegorical level – the red Saab, Kafuku and Misaki all representing an aspect of Japanese society – as Hamaguchi stealthily embeds a symbolic Japanese flag in the film’s scenes and aesthetics abundantly. Examples include an ultra-long shot showing the red Saab speeding along the highway of Tokyo amidst its surrounding white buildings, or the car amidst the snow of Hokkaido, or importantly, in the film’s ending scene when it is revealed that Misaki is now in Korea and the red Saab is parked amongst a carpark of white cars.

But Hamaguchi does not stop there. He further aggrandizes his exploration to transnational traumas as well. The Uncle Vanya production that Kafuku directs in the film features a multinational cast with each cast member performing in their own language. Thus the Taiwanese female lead who plays Sonya speaks Mandarin Chinese. Kafuku also casts a Korean actress who cannot speak and communicates with sign language. The celebration of multilingualism perhaps suggests Japan’s need to embrace diversity as the viewer is presented with a dissonant harmony during the rehearsal scenes and the few shots of the actual theatre performance.

Thus, if Murakami’s text mostly explores Kafuku’s trauma of being betrayed by his wife, Hamaguchi’s film adds into the mix national traumas of Japan – both traumas that Japan had experienced and that Japan made other countries or communities experience. The mute Korean actress for example takes on an allegorical meaning, representing Japan’s neglect of the zainichi Korean population. Although some may find a muted Korean character in a Japanese film problematic, one central message of the film is perhaps that trauma and living come in pairs, and ‘how to live on with trauma’ is not something unique to Japan.

One may even be tempted to see Hamaguchi suggesting potential solutions. In Murakami’s source text, Kafuku being forced to relinquish the driver’s seat to Misaki allows him to let go of rational control (the steering wheel) in his life and verbalising, in the passenger seat and perhaps for the first time, his feelings of being betrayed by his wife. Allegorically, perhaps it is now time for women and the younger generation (embodied by Misaki who nonetheless has her own trauma) to take charge and help the nation face with its traumas, as Misaki has helped Kafuku.