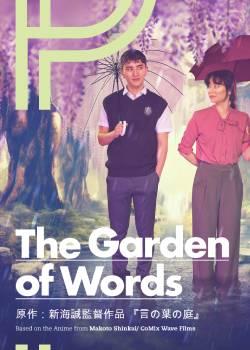

The Garden of Words

Directed by Alexandra Rutter

Co-adapted by Susan Momoko Hingley & Alexandra Rutter

Based on the anime Kotonoha no niwa by Shinkai Makoto

Whole Hog Theatre in association with Park Theatre

Park Theatre (10 August - 9 Spetember 2023)

Review by Laurence Green

Before Totoro. After Totoro. Such is the incredible degree of success (six Olivier Awards to say the least) that greeted the Royal Shakespeare Company’s theatrical adaptation of the Studio Ghibli classic My Neighbour Totoro on its 2022 run at the Barbican that a year on, it remains hard to approach Whole Hog Theatre’s premiere of The Garden of Words in isolation. Indeed, sharing as it does a number of cast members with My Neighbour Totoro, as well as drawing on a similarly impressive smattering of choreographed on-stage movement and puppetry, this adaptation of the Shinkai Makoto anime feels like it draws from very much the same aesthetic DNA, albeit put here to an entirely different thematic and tonal use.

For here, unlike Totoro - or indeed Shinkai’s own fantastical big-screen successes Your Name (2016), Weathering With You (2019) and Suzume (2022) - we are presented with a wholly naturalistic tale, and a surprisingly adult one at that. There is on-stage smoking, swearing and even violence. Shinkai’s anime works have always been marked by their visual fidelity to life - photo-realistic even at times - but this time, that quality is matched by both a narrative and characterisation that stands as refreshing in how overwhelming human it all feels.

High-schooler Akizuki Takao (Hiroki Berrecloth) dreams of shoes - or rather, the dream of escaping his humdrum Tokyo existence and studying in Italy to become a shoemaker. His favourite place to sketch out his footwear designs is Shinjuku Gyoen. At this park, he meets a mysterious woman - Yukino Yukari (Nakagawa Aki) - and over exchanges of food and classical Japanese poetry, the two form an unlikely bond. The tranquillity of these serendipitous meetings is cast in contrast to the tangled, messy existences both characters lead beyond the confines of the park. In their brief moments together, they find peace - two souls drawn to each-other in their emotional similarity. It is through the introduction of others - family, colleagues, classmates - that life’s infinite complexities are set into motion.

For the first 20-30 minutes or so, the rapid intermingling of characters and the bite-size vignettes of their lives can prove disorientating - but as we become familiar with our protagonists, and the way their lives intermingle and intwine within the lonely chaos of contemporary Tokyo, the magic of this staging begins to become apparent. Though Takao and Yukari are clearly the lead players here, every character is given their moment in the spotlight; from Takao’s earnest brother Shota (James Bradwell) to rebellious school-girl Aizawa Shoko (Ito Shoko) and the punkish but good-hearted gym teacher Ito Soichiro (Ota Mark Takeshi). The story never shies away from honestly presenting each of their motivations, quirks and flaws - and they are all flawed in their own way - as well as the snooker ball-like chain of cause and effect between them. In a city of millions, all are ultimately linked, and as Yukari points out on numerous occasions, we are all ultimately weird.

As the production reaches its narrative and emotional peak at the end of the hour-long first act, the full moral complexity of Takao and Yukari’s relationship is made plain to both characters, as well as the audience. The short, 30-minute second act offers a conclusion of sorts, but it is an ending that is as ambiguous in its bittersweet qualities as it is about whether our lead characters have really redeemed themselves. Just like real life, there are no true “happy endings”, only continuations as we move from one page of our stories to another.

And yet, this take on The Garden of Words carries with it such a sense of fulfilment - chiefly because while it holds so true to the emotional core of the anime version, in its transformation to an English-language (and might we say it, a British-accented) staging it speaks with an augmented universality. Yes, its realisation of an urban Tokyo is spot on - from its clever embodiment of a packed Yamanote line train and the ever-present karasu (crows) to the beer cans, umbrellas and tatami that make up the accoutrements of life - but we are made to believe the core essence of the story to be one that could take place anywhere. From high-schoolers to adults, from love to hate - the same drives and abuses of power stem from an anyplace that is all the more impactful because it is divorced from many of the tropes that define so many of the more populist anime narratives. There are still archetypes at work here, but those drawn from the hyperreality of life. If Totoro was a nostalgic idealisation of Japanese rural existence, then The Garden of Words hits home for the polar opposite reason. It deconstructs idealisation and instead - as its particularly apt iconography suggests - quite literally lets us walk in its characters’ shoes.

As the next in what will no doubt - we hope - be a building wave of anime-to-theatre adaptations in the UK, this take on The Garden of Words feels like it has struck on the very essence of right time, right place. Making accomplished use of the intimacy of Finsbury’s Park Theatre as a setting, the production’s utilisation of the full panoply of contemporary stage-craft feels all the more impressive because of the pocket-sized world in which it emerges from. In the blink of an eye, a tatami-matted room becomes a tranquil Tokyo park, becomes a cold, clinical school classroom. The stellar cast, who all feel like picture-perfect matches for the roles in which they inhabit, are the icing on the cake.

With Totoro, it felt from the very beginning that success was assured, a pre-made audience of Studio Ghibli fans and families ensuring a sold out run from the word go. But with The Garden of Words, the envisioned audience feels more of an enigma: fans of the anime, certainly, those with an interest in Japan, likewise. But what is perhaps the surest testament to this staging’s skill is that it feels like a production that could also exist quite apart from both of these audiences if it needed to. Born from the DNA of anime - but speaking with a theatrical voice that goes well beyond it.