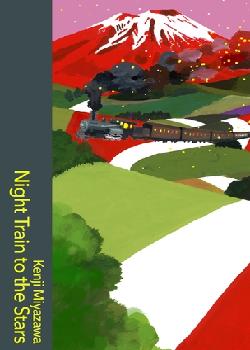

Night Train to the Stars

By Miyazawa Kenji

Translated by John Bester and David Mitchell

Vintage Classics (2022)

ISBN: 978-1784877767

Review by Renae Lucas-Hall

Night Train to the Stars is a collection of short stories written by Miyazawa Kenji (1896 – 1933), one of the most cherished and enchanting authors in modern Japan. Hailing from Hanamaki in Iwate Prefecture, an area renowned for hot springs and stunning mountain ranges, Miyazawa loathed his family’s pawnbroking business because it took advantage of poor farmers, so he chose a career in agricultural science. Unfortunately, he passed away at the age of 37 without ever experiencing fame, despite having written over 100 stories and 800 poems. It was his family and friends who revealed his genius to the world. His Buddhist faith is evident in most of his stories, posing philosophical and religious questions and answers. Creating a world of fantasy comparable with Narnia in The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe (1950) by C. S. Lewis, Miyazawa “mixed local elements with his imagination to create a literary world that is truly magical”, according to the introduction by author and lecturer Nagai Kaori. “Miyazawa called his fictional world Ihatov, which he defines as Iwate as a dreamland that really exists in his mind. In his dreamland, everything is possible” (p. xiii).

The first tale of the collection titled Night Train to the Stars takes place in Japan on the day that celebrates “the Festival of the Milky Way”. A young boy called Giovanni and the rest of his class are encouraged by their teacher to go outside and look at the stars after school. The first few pages are a lesson on the Tanabata festival or “Star Festival” that takes place once a year on the 7th day of the 7th month. Everything seems ordinary up until the section titled ‘Milky Way Station’ when one is transported into a unique world of make-believe. Giovanni and his friend Campanella can run like the wind in this fantasyland without getting out of breath, geese taste like sweet candy, and maps given out at the Milky Way Station are made of obsidian. Giovanni’s train ticket allows him to travel all the way to Heaven and beyond.

In Japan, fox spirits or kitsune can shapeshift, bewitch, and trick people. The theme is jealousy in the next story The Earthgod and the Fox. This fox reminds us of people who stretch the truth to impress others. However, the death at the end of this story proves that a lot of Miyazawa’s fables may not be meant for children.

Foxes are mentioned again in the tale, General Son Ba-Yu. “They can put a whole army of close on ten thousand under their spell” (p.66). This is a story of three Chinese doctors who are also brothers living in a country called La-yu. General Son Ba-yu returns to his village from “the sands beyond the Great Wall” but he has been riding for so long he is stuck to his horse and he cannot dismount! The doctors rectify all his pains and problems with their magic medicines and potions.

Ozbel and the Elephant is a story about greed and trickery. Ozbel puts an elephant to work and takes advantage of him until his friends rescue him. In The First Deer Race, the protagonist Kaju can suddenly understand what the deer are saying (deer are considered messengers to the gods) and the famous bear hunter Fuchizawa Kojuro can understand the bears talking in The Bears of Nametoko. In this narrative, the death of the bear hunter is treated with a high level of respect showing the fine line between the living and the deceased as both are considered to be of great importance. This is connected to both Buddhism and Shintoism.

Mr Kaneta Ichiro is invited by the Wildcat to a trial as a judge in The Wildcat and the Acorns. The fact there are 300 tiny acorns all wearing red trousers reminds the reader of Gulliver’s Travels (1726) by Jonathan Swift and his interactions with the Lilliputians. The acorns are competing to be the roundest, the biggest, or the tallest. The Wildcat offers a reward to Ichiro for helping him which brings to mind the Japanese customs of on (benevolence) and giri (obligation). Gift giving is an essential aspect in Japanese culture for fostering social connections between friends and business partners. The Wildcat also arranges for a carriage to transport Ichiro back home. "A magnificent carriage, constructed with a large white mushroom, materialized before them. It was pulled by a peculiar grey horse, resembling a rat in appearance." Filmmaker Miyazaki Hayao, a fervent admirer of Miyazawa, may have been inspired by this mushroom carriage described on page 103. It could have potentially influenced the creation of the nekobasu or catbus in the Studio Ghibli animation film My Neighbour Totoro (1988).

Remember the ‘Drink Me’ potion in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by Lewis Carroll which makes the drinker shrink in size? What about the red and blue pill that Morpheus offers Neo in the film The Matrix (The Wachowskis, 1999) ? In another Miyazawa’s tale, The Man of the Hills, a Chinese man offers the protagonist a drink which turns him into a small box on page 136. Later in the story, he is offered a pill to change him back to his normal self.

The Thirty Frogs is a cautionary tale which is not unlike a yakuza trap in Shinjuku. These 30 frogs work hard and enjoy their daily tasks. Everything goes well for the frogs until they came across a new shop with a sign ‘Imported Whisky – two and a half rin a cup’ (a rin is one-thousandth of a Japanese yen) on page 166. This shop is run by a bullfrog who plies them with whisky. When they cannot pay their bills, he sets them to work, keeping them inebriated so they cannot escape but, in the end, the bullfrog does shows remorse.

One of the most charming stories is The Fire Stone which features a young hare named Homoi who saves a baby bird from drowning and in doing so he receives a fire stone from the king. It is a special and very beautiful stone, and he can see the Milky Way inside it when he put it to his eye. In this enchanting yarn, the animals gracefully emulate the Japanese tradition of bowing. A heartwarming moment occurs when the mother bird instructs her young lark to bid farewell with a proper bow. As readers delve into this delightful chronicle, reminiscent of Beatrix Potter's The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), they will find themselves captivated by its gentle lessons on goodness and kindness.

Miyazawa's fairy tales and fables not only captivate readers with their unforgettable characters and superb descriptions of nature, but also offer profound insights into society, relationships, the class system, values, vices, and the importance of acceptance. By reading his stories, we are enriched with a sense of joy and inspired to improve ourselves as individuals and as a collective.