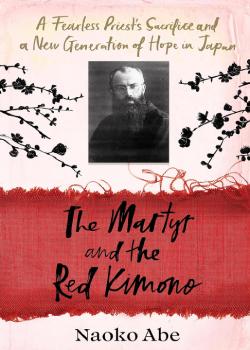

The Martyr and the Red Kimono

By Abe Naoko

Chatto & Windus (2024)

ISBN-13: 978-1784744533

Review by Laurence Green

It is the 14th of August, 1941. A Polish monk called Maximilian Maria Kolbe has just been killed by lethal injection in Auschwitz, following weeks of starvation. Many years later - he will be canonised as a saint; his death in the Nazi concentration camp standing as the ultimate sacrifice - he gave up his life to save another prisoner.

Kolbe’s life and death would go on to have the most striking of reverberations across the world. He had made his name founding a movement of Catholicism and running Poland’s largest publishing operation. He would spend a number of years in Japan, ministering to the descendants of the “hidden Christians” that had practised their faith secretly for centuries, away from the prying eyes of the Shogunate. And indeed, it would be this connection to Japan that would see his life inspire two Japanese men; Ozaki Tomei - who was just seventeen when the US dropped an atomic bomb on his home in Nagasaki, and Asari Masatoshi - who worked on a farm in Hokkaido during the war and was haunted by the inhumane treatment of prisoners in a nearby camp. What follows is a kind of biography in triplicate of these three individuals - separate but interlinked in the most surprising of ways.

The Martyr and the Red Kimono is very much the spiritual successor to Abe Naoko’s previous book, ‘Cherry’ Ingram: The Englishman who Saved Japan’s Blossoms, which went on to become a surprise bestseller in the UK, no doubt spurred on by readers raised on a diet of Gardeners’ World episodes and the enforced isolation of the pandemic years. The cherry tree focus is this time interwoven with the thornier themes of war and religion, resulting in an at-times complex multi-segmented narrative that flits regularly between characters and themes, taking in the entirety of the 20th century as its historical scope.

The book’s opening chapters, which detail Kolbe’s early life and the significance of his efforts in both Poland and Japan, are in many ways the most difficult going; wrapped up as they are in the twin efforts of Polish nationalism and Christian evangelism that would become drivers for Kolbe’s life. Against a backdrop of rising tensions in Europe, Kolbe’s fiery patriotism is portrayed in meticulous detail - and becomes easier to grasp once cast against the more familiar narratives of the beginnings of Second World War .

Here, the pace of the book quickens, and the ceaseless momentum with which it proceeds to what we know must be Kolbe’s inevitable end is portrayed with a filmic quality that is as gripping as it is emotional. It is the lives of the two Japanese who were to look to his life for inspiration, however, where the book’s real heart truly begins. In Ozaki Tomei, and the horrific detail with which the loss of his family in the Nagasaki atomic bombing is detailed - including maps and illustrations - we are in many ways offered the flip side to the ‘American’ narrative of the bombs so recently depicted on the big screen in Oppenheimer. Ozaki’s story is a war story on the most human of scales, terrible in its bleakness. To his dying day, he would become a strident, outspoken voice on the horrors of nuclear war.

We come, then, to the third of the book’s key figures - Asari Masatoshi - who would end up devoting his life to sending cherry tree saplings around the world as part of peace efforts; including to America and Poland. Controversial donations to China and North Korea in the 1970s and 80s would draw unsettling attention from the Japanese authorities during the height of the Cold War era. As we move toward the present day, Abe herself becomes central to the narrative, as she tries to track down the remnants of Asari’s historic cherry tree donations to Catholic convents in Poland - do any of Asari’s donations still survive?

It is worth noting that the significance of the titular ‘red kimono’ is not truly revealed until the very closing pages of the book - and as striking as its appearance might be, it stands as only one strand in a book whose various components will appeal variously to different readers. Is this a pacey military history, teasing out new angles by which to look at the Second World War? An eye-opening personal narrative of the impact of the nuclear bombing on Nagasaki? Or a deep, contemplative reflection on Catholicism and its existence in communities as disparate as Poland and Japan? The book is all these things individually - but also in the sum of its parts, something more - but only if the reader is willing to put the work in and hold fast to the connecting narrative.

Ultimately, the winning charm of Abe’s book - as it was with the Cherry Ingram biography - is the epic scale of its historical lens, which draws so much of its power from human subjects that lived through, and were immersed in, the full panoply of change our all-too fragile world underwent through the 20th century. Figures like Ozaki and Asari - from humble roots to great ambitions - feel like indomitable fighters pushing against the very fabric of history’s grand narratives of war and peace; striving ever onward with goals which are both deeply personal and also tied up with the very idea of humanity. Can a single cherry tree, ten, or a hundred even, make a difference in a world still ripped apart by conflict on a daily basis? The answer is ambiguous - but what Abe’s book seems to offer up, is that it is from the fight itself, the eternal struggle, that meaning of some sort can be drawn.