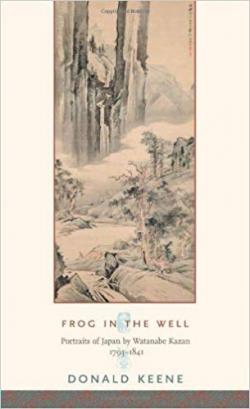

Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan 1793-1841

Frog in the Well: Portraits of Japan by Watanabe Kazan 1793-1841

By Donald Keene

Columbia University Press, New York, 2006

ISBN 0-231-13826-1

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Watanabe Kazan is nowhere near as well known in western countries as his contemporary Hokusai, whose works had such a huge influence on western art. But Watanabe Kazan, as Keene's new biography demonstrates, deserves to be studied not only as an artist who produced works of the highest quality but also as a samurai who was both a student of Confucianism and of Rangaku (Dutch i.e. foreign learning) and who warned the bakufu of the dangers it faced from abroad.

Donald Keene has produced a fascinating and readable study of a remarkable figure of the late Tokugawa era. As we would expect from someone of Keene's outstanding scholarship the book is based on thorough research.

Watanabe Kazan was a samurai from the Tahara domain who spent much of his life in Edo. He might have become a Confucian scholar if he had not had to earn money to relieve his family's poverty. He accordingly took up painting to earn a living. He wanted to know more about the world outside Japan and studied books which had been translated from the Dutch. This led him in due course to write Shinkiron (Exercising Restraint over Auguries) in which he praised elements of western regimes and pointed out that the British could, for instance, argue that ships might need help in emergencies. He stigmatised the attitude of the Japanese authorities as being like that of "the frog in the well" (seia) who could not see what was going on around them. It was this sort of criticism of the government which led eventually to his imprisonment and finally to his suicide when he feared that his criticisms of the government might lead to trouble for his feudal lord. Kazan remained faithful to the end to the samurai traditions in which he had grown up despite his interest in foreign learning.

Keene draws an interesting picture of Japan during Kazan's life and of the intellectual currents of the time. One of the most enjoyable chapters deals with Kazan's travels in Japan; in this he brings to life many scenes which help the reader to appreciate what life was like in those days.

Above all, however, Kazan's fame rests on his abilities as a painter. He belonged to what has been termed the literati school (Bunjinga). The Bunjin were "gentlemen of culture and leisure who were devoted to all aspects of Chinese culture." Some of his landscapes in this style are fine works of art. Among these I particularly liked Tiger in a Storm from 1838 (page 140). Kazan also produced genre paintings which stand comparison with works by Hokusai. Among the series of paintings in Kazan's Isso Byakutai I was impressed by the realism and humour of one showing a terakoya (temple school) (pp56/57) where "three pupils sit in front of their teacher and intone something from the Chinese classics while all the other boys are fighting, screaming, and doing everything but practising the calligraphy lesson on the desks before them." But Kazan stands out as a portrait painter.

Portrait painting in Japan before Kazan had tended to be stylised and individuality at best glossed over. Kazan brought a new realism to the art. One of his most striking portraits is that of Sato Issai (1821) (page 61), produced before Kazan had studied western painting techniques in so far as information about them was available to him.

Keene also introduces many other effective portraits including a fine one of Takami Senseki (page 119) in the Tokyo National Museum which has been designated a National Treasure.

Anyone interested in the history of the Tokugawa era and of Japanese art will find this book fascinating.