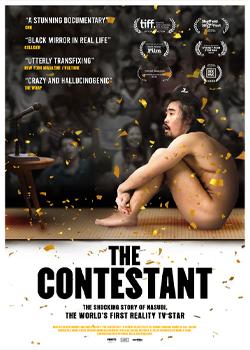

The Contestant

Directed by Clair Titley

Available to watch in BBC iPlayer

Review by Mayumi Donovan

How far should you go in creating the biggest TV show? That is the question I was left asking after watching The Contestant, a documentary film directed by Clair Titley. It revisits a reality TV programme that aired in Japan in 1998, blending original footage with recent interviews with those involved.

I remember this programme vividly — I watched it in real time. Denpa Shonen was a hugely popular Japanese show created by the “pioneer” TV producer Tsuchiya Toshio. It placed people in survival situations, sometimes catastrophic, and audiences were captivated by the unbelievable stories. Literally everyone was watching and talking about it. Did I laugh at the time? Probably… but now I feel deeply uncomfortable about it. It was a crazy era in Japan, with many bizarre and extreme TV shows. The line between what was ethical and what was not had become blurred.

The Contestant tells the story of Hamatsu Tomoaki, known as Nasubi (meaning “aubergine” in English) — a nickname from childhood due to his long face. He moved from Fukushima to Tokyo, dreaming of becoming a comedian, and entered a competition organised by the legendary Tsuchiya. By pure chance, he “won” the audition through a lucky draw. Watching his delighted reaction is heartbreaking, as he had no idea what he had actually won.

He was immediately blindfolded, given headphones and taken to a secret location: a tiny apartment containing only a table, cushion, telephone, postcards, pen, notebook, radio, and a lot of magazines. He was ordered to strip naked and told he must survive solely on prizes won from magazine competitions. He could only leave once the total value of his winnings reached one million Japanese yen. This became the infamous TV show Denpa Shonen – A Life in Prizes.

It seems astonishing now that anyone could agree to such a cruel challenge. Even more surprising was the fact that there were no signed contracts in place at the time. Perhaps Nasubi’s own personality played a part — he came from the countryside, was slightly naïve, and deeply trusting. There were also hints from his past — in the film he speaks of being bullied at school, and how making people laugh became a form of self-protection. We have to remember that this was the very first reality TV show in the world and nobody had any experience of how to react to such situations.

Over the months, he won prizes ranging from the practical, such as rice, to the bizarre, like dog food and even a live lobster. All his actions were captured on video, but he was told that most of it would not be broadcast — which was untrue. The footage was heavily manipulated so viewers saw only his exaggerated, comical reactions, while the reality — loneliness, depression and even suicidal thoughts — remained hidden. To me, it feels as though he was the subject of a human experiment, born from Tsuchiya’s obsession. And we, the viewers, were complicit. The hunger for outrageous television drove the cruelty to extreme levels.

After eleven months, Nasubi finally won enough prizes to leave the apartment. But his relief was short-lived, as Tsuchiya had devised yet another cruel twist. For Tsuchiya, creating “the biggest story” in television was all that mattered; humanity and ethics seemed secondary, if they existed at all.

Following Denpa Shonen, Nasubi became a household name — but a changed man. The film highlights his transformation through a montage of his face over the days, weeks, and months. He reflects on his experience and speaks openly about the psychological damage: mistrust of others, difficulty forming relationships and the need to relearn how to connect with people. One of the cruellest aspects was that he did not know it was being broadcast to an audience of millions, nor that it became the first reality TV show in the world, even before Big Brother. He had no idea he was one of the most famous people in Japan while he was suffering, naked, in a tiny room.

The director, Clair Titley, says in her interview with Directors UK that her mission with the film was to help Nasubi reclaim his story. She focused on telling his story rather than the show’s. The film avoided explicit judgement, instead leaving it to the viewers by presenting the facts and a wide range of interviews with Nasubi, his family, and those involved in production. The visual transformation of Nasubi’s face over time is powerful, conveying his dramatic physical and mental decline. His own words are revealing, as are the moving comments from his family and friends. His mother’s comments are particularly emotional — the pain of seeing her son suffering on TV but being unable to reach him is heartbreaking.

In contrast, the comments from Tsuchiya and the production team seem quite frank. I do not think I saw a hint of regret from Tsuchiya for creating such a show. He still appeared to celebrate his creation, proudly recalling himself as a “genius” and remembering the finale of the show, where Nasubi was revealed live in the studio in front of a huge audience, naked. He claimed he thought “it will go down in history.” An apology does not seem to be in his nature, though at least he admitted to being a “devil.”

Titley successfully balanced the cruelty of the reality show with the hope Nasubi eventually found. After his celebrity years, the 2011 tsunami brought him back to Fukushima, where he was devastated by the destruction but moved by the warmth of the community. Helping others there gave him a renewed sense of purpose. Despite setbacks, he deepened his sense of fulfilment and reinforced his commitment to helping people. The film’s portrayal of his efforts, his family ties, his friendships, and his bond with Fukushima is deeply moving. In many ways, as Tsuchiya himself put it, “Fukushima saved him.”

The film cleverly re-creates Denpa Shonen with English translations of on-screen messages and narration. It preserves the original comical tone of the show while contrasting it with the stark reality revealed in the current interviews. The montage footage of 1990s Japan adds atmosphere, showing what life was like at the time. The music, including tracks by Cibo Matto, enhances the quirky sense of 90s Japan, while Ane Brun’s acoustic version of “Big in Japan” brings a quiet yet emotional melancholy.

The film also shows a reunion between Nasubi and Tsuchiya after fifteen years. I was surprised that Nasubi did not display open anger towards Tsuchiya — though that does not mean he has forgiven him. I doubt he ever will. Titley says in her Directors UK interview that it was actually Nasubi who asked for Tsuchiya’s involvement in the film, and she believes Tsuchiya agreed because he felt he owed something to Hamatsu. There are signs that, despite everything, there is a unique relationship between the two of them.

There is some relief in the positive outcome — Nasubi finding his own purpose and happiness through reconnecting with people — but no one should have to endure such extremes to discover it. The cost to him and his family was far too high compared to what he gained. It is also notable that the programme was only ever broadcast in Japan; it was never shown abroad. In today’s social media era, that would be unthinkable, yet at the time, people outside Japan barely knew of the show. Reading people’s reactions to the documentary, many could not believe it was real — I can hardly believe it myself. I do not want to dismiss it as “just a different era.” One thing is certain: there is absolutely no way such a show could ever be broadcast today — although the appetite for extreme reality TV show remains endless.

Ultimately, the documentary raises a question: what drives us to watch people endure extreme, sometimes cruel, situations? The Contestant reminds us that we share responsibility for the society we create. No one should suffer for entertainment – It remains the same issue we face today.