In Lotus-Land Japan

By Herbert Ponting

Macmillan And Co. Limited, London (1910)

Digital version available online at the Open Library

Review by Susan Meehan

Herbert Ponting, the British photographer on Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole in 1910, “created unparalleled visual records of Antarctica and of Scott’s last expedition and great scientific endeavour, a legacy which alone guarantees his place in photographic and film history”.[1] Less well known, he also left behind thousands of evocative images of Japan, and three Japan-themed books. “From the advent of photography in Japan until the end of the Meiji period, he is the best photographer to have worked in that country”.[2]

Ponting’s first trip to Japan came in 1900, when he was living in California. He was commissioned by CH Graves, a stereoview company, and by the magazine Leslie’s Weekly to travel to Asia. The stereoview company wanted to update its popular stereoviews of Japan, while the magazine had Ponting cover the Philippine-American War as well as the Boxer Rebellion in China.

Ponting returned to Asia and Japan many times during the first ten years of his career. As well as further commissions to take photographs in Japan, he covered the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. A skilled cameraman, he became a regular contributor to Graphic, the Illustrated London News, Pearson's and Strand Magazine.

During 1905 and 1906, Ponting collaborated with Ogawa K, a leading Japanese photographer, to produce his books Fuji San, which contained 25 views of Mount Fuji, and Japanese Studies – comprising 52 images accompanied by captions and poetry. Between 1909 and 1910, Ponting was finishing his Japanese memoir, In Lotus-Land Japan, while also preparing for the 1910 Japan-British exhibition at White City, Shepherd’s Bush, at which he exhibited many enlargements of his photographs.

When Ponting first went to Japan, his main objective was to photograph the country to his heart's content. During his time in Japan, however, he also took plentiful notes. As he goes on to remark, “and as the fortunes of a wanderer led me several times back again to this beautiful land, these notes became so voluminous that the suggestion of friends, resident in Japan, that I should embody my experiences in a book, written round some of my photographs, was an idea which presented no great difficulty in the way of achievement” (preface, p. V). In Lotus-Land Japan was the result, based on Ponting’s three years of travel, criss-crossing Japan, and including 107 photographs – in colour and monochrome – of various facets of Japan in all seasons. The images of temple bells, fortune tellers, a Buddhist abbot, tea bushes on the hills, rice growing on the plains, public baths, and at the crater’s brink at Mount Aso – are spellbinding and each conjures a story. Rumbling in the background of some of his trips (particularly as described during his travels around Hiroshima) is the Russo-Japanese War.

The memoir comprises 20 chapters, including - just to give a flavour of his themes and travels – ‘Tokyo Bay’, ‘An Ascent of Fuji-San’, ‘The Artist-Craftsmen of Kyoto’, ‘The Great Volcanoes: Aso-San and Asama-Yama’, and ‘The Inland Sea and Miyajima’. A mere look at the chapter names whets the appetite and gives an idea of the spread and depth of his travels.

The first chapter, in which Ponting describes his excitement at arriving at Yokohama from San Francisco by ship, is full of wonder and awe. It deftly draws in the reader, who wants to continue on this journey with this most erudite and sympathetic traveller.

“From the time we left San Francisco’s fine harbour behind us, few had been the daylight hours when the heavens were not mirrored in the ocean” (p. 1). His description of the cloudless sky is just as short example of his stylish writing.

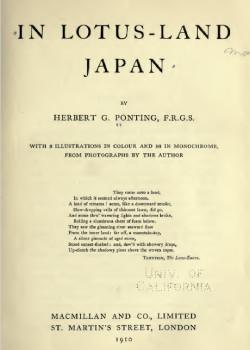

With his photographer’s eye, Ponting writes beautifully, poetically and at length about Mount Fuji, one of his favourite subjects: “Whilst my attention was absorbed with the fishing boats the morning rapidly grew, and now the delicate outline of that loveliest of all mountains of the earth — that wondrous inspiration of Japanese art, Fuji-san — was softly painted on the western skies. The grey of dawn was shot with pink, and blue, and amber, and high in the iridescent azure, far above the night-mists clinging to the land, the virgin cone of Fuji hung from the vault of heaven” (p. 3).

Ponting took hundreds of photographs of Mount Fuji from all sorts of angles and at different times of day, smitten as he was by the volcano. The book also features an account of one of Ponting’s treks up Mount Fuji, which was (and can be) a hairy experience. He ended up stuck on Fuji for a few days (in an inn) sheltering from the storms and nursing incapacitating headaches. The account is vividly rendered.

Herbert Ponting, In Lotus-Land Japan, p. 152

Ponting felt in his element in Japan. A perfectionist himself, he appreciated the skill and perfectionism of the Japanese craftsmen he encountered, and he formed a very positive impression of the Japanese whom he regarded as extraordinarily polite and very clean. He was also exceedingly complimentary of the kindness, courteousness, and honesty of the Japanese people he encountered.[3]

Ponting’s observations of Japan are deep and insightful. Having seen stereoview photographs of Japan before leaving San Francisco, Ponting would have had some kind of image in mind, but this was surpassed by what he encountered on arrival. As well as taking photographs of the most famous points of interest in Japan, he veered off the tourist track and included: “a few experiences I had far from tourist haunts; and, to lend variety, have added some that befell me during the late war, together with accounts of the wonderful work of the present-day artist-craftsmen and of the old-time swordsmiths” (preface, p. VI).

As well as a memoir of his travels in Japan, Ponting packed his book with a substantial amount of context and history. He gives a detailed account of Buddhism and its six principal sects, while also writing about different varieties of tea, and penning beautiful pieces on rice and tea cultivation, as well as on the tea ceremony. There are some wonderful sections on fireflies, the unrivalled popularity of tea, and the growing acceptance of - indeed attractiveness of beer! He also talks about the Kamakura shogunate, the story of Yoshitsune and Yoritomo, and of the creation myth centring on Awaji in the Inland Sea where the Creator Izanagi and the Creatress Izanami settled and gave birth to all the other islands of the Japanese archipelago.

In Lotus-Land is a real treasure trove of eclectic information, and nostalgia-inducing for the reader who relates to the “hotaru-gari” (“firefly viewing”) and to revelling under the cherry blossoms, amongst other such experiences. Many contemporary travellers to Japan would confirm Ponting’s accounts of the cherry blossom viewing parties, “The crowd is warm with humanity, joyous with humour, and amiable with courtesy. No irascibility or pugnaciousness mars the merriment, and roughness is conspicuous by its absence, for the Japanese crowd is a lovable crowd” (p. 217).

There is much humour in the book. Ponting rejoices in his account of the “flashlight photographs” he took on the balcony of a hotel in Kumamoto, and which were mistaken for meteors by a journalist who caused quite a kerfuffle when he reported his “scoop”. Elsewhere, while writing about shoji (sliding doors which use paper in the lattice frames), he mentions that children are prone to peeking through shoji. “Occasionally you may detect a finger in the act of making such a hole, or enlarging one already made”. “The paper, however, is fixed to the framework so tightly that when a finger is poked through it, it makes a very audible “pop”. To obviate, this the tip of the finger is moistened, and a slight twisting motion enables the hole to be made quite noiselessly” (p. 270-271). I immediately pictured the scene, finding it hilarious.

Ponting’s recollections of Kyoto are very evocative, tinged with a real yearning for the city. He describes rambling over the hills, roaming amongst its old temples, searching through its innumerable curio and pottery shops, visiting artist-craftsmen, viewing cherry-blossoms and “shooting the rapids of the lovely Katsura river”. He paints a portrait of a bustling and thoroughly exciting place, and shared numerous memories that “have left this enchanting old city dearer than any other to my heart” (p. 4).

The photos included in the Kyoto chapter are wonderful: a photo of Kiyomizu Temple in the moonlight, of rickshaws driving down avenues of abundant and beautiful bamboo, and of travellers shooting the rapids are all stunning.

Herbert Ponting, In Lotus-Land Japan, p. 12

Ponting’s section on the artists and craftsmen of Kyoto is sublime. He was interested in the embroidery and ceramics being created and managed to have meaningful conversations with various Japanese artists, some of whom spoke English. He also seems to have picked up a reasonable amount of Japanese language during his various trips to the country which helped his communication. As bronzes, silks, embroideries, porcelain, cloisonné, iron-wares, and a number of other products for which Japan is noted emerged from Kyoto, he wanted to recognise and celebrate the skill of the artists involved.

The section on Japanese women who were much admired by Ponting, is my least favourite, though its reference to the bombardment of Kagoshima by the British navy in 1862, just eight years before Ponting’s birth, is engaging. Having been swept away by his lyrical writing and artistic photographs, perhaps I approached the chapter with overly high expectations, hoping that Ponting would have had more original, progressive, and enlightened views than many of his contemporaries. Alas, his repetitive references to Japanese women as “gentle” and “little” is irksome, but understandable given the historical context. The book was published in 1910, seven years or so after the start of the women’s suffrage movement in the UK. It wasn’t until 1928 that women of over 21 were able to vote in the UK (in 1918 women over 30 who met a property qualification were allowed to vote).[4]

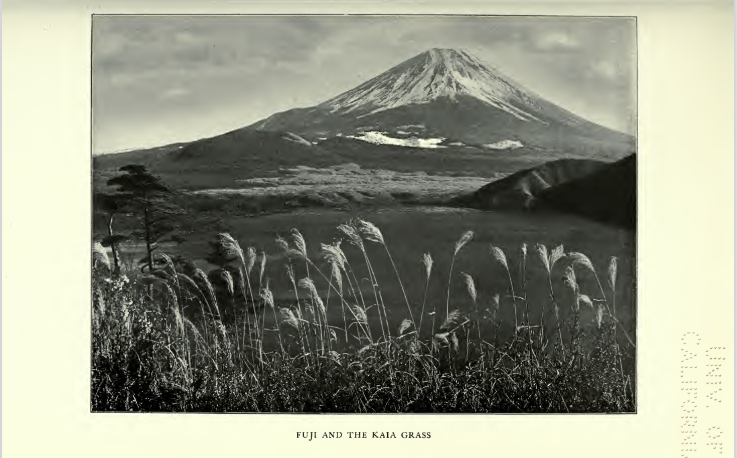

Ponting’s ode to the tatami and the hibachi (“brazier”) is wonderfully entertaining and descriptive, as he describes domestic life centred on the tatami and circulating around the hibachi: people are warmed, tea is brewed, guests entertained, and chess played by the hibachi. The chapter includes a lovely photo of a woman in kimono by the hibachi, a cup of tea by her side, as she writes a letter using brush and ink.

Herbert Ponting, In Lotus-Land Japan, p. 268

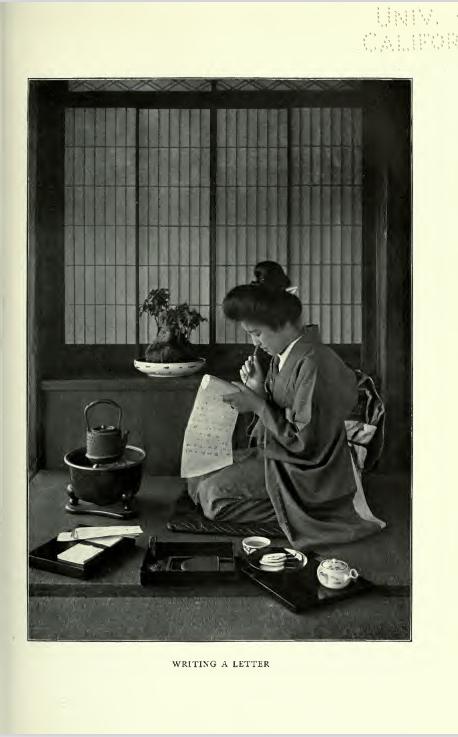

Mentions are also made of the futon, of course, and the pillows of the time: more of a small hard bolster for men and a lacquered stand with a soft pad on top for the women. There is a wonderful photograph of a woman using one of these “makura” pillow. Her neck rests on the pad, but not her head, allowing her coiffured hair to remain pristine (p. 272-273).

Herbert Ponting, In Lotus-Land Japan, p. 272

Ponting was keen to visit Hokkaido and meet the Ainu, native to Hokkaido. He’d already formed an impression of the Ainu, referring to “that strange, hairy race who were the aborigines of the land before the Japanese arrived and took it from them” (p. 306) and who are “held in utter contempt by the clever, enlightened Japanese, and are left alone to work out their own salvation” (p. 314-315) This perception of the Ainu, gained from speaking to Japanese on the main island of Honshu, rubbed off on Ponting, who says they have no arts or crafts, literature or ambition. “If they should in course of time become extinct their place will be taken by a race to whom humanity in general owes a greater debt” (p. 321). He travelled to Ainu settlements on the East coast and visited lakes and volcanoes with a Japanese interpreter. He was intrigued by the tattoos on the women’s upper lips and which were occasionally seen on the backs of their hands as well as on their foreheads and arms. He concedes that the women have a childish charm and that the Ainu men appear patriarchal and distinguished, but that’s as far as his compliments go in this case.

In contrast to Ponting’s prejudices, when a group of Ainu travelled to take part in the previously mentioned 1910 Japan-British exhibition at White City in London, The Daily News on 16 April 1910 referred to the Ainu as being “the politest people on earth.” “They have beautiful brown eyes, swarthy complexions and black hair” and an “almost Tolstoyan appearance” given their long hair and attire.[5]

Early on in his memoir, Ponting refers to the Japanese love of flowers, mentioning, in particular, cherry blossoms, irises, wisteria and chrysanthemums. He is full of wonder for the lotus flower – a symbol of Buddhism – and his reverence for it is akin to his respect and admiration for Japan and its people. He describes the lotus’s “great pink blossoms”, which “typify a chaste and noble heart—unstained, unsullied, and untouched by the insidious breath of evil with which life is permeated—opening to the light of truth and knowledge” (p. 229).

Japan certainly left a deep impression on Ponting. His broad-spanning, largely generous insights, and first-rate photographs would be of great interest to anyone curious to learn more about Japan and how it was appreciated in the early twentieth century by this well-travelled and perceptive man. There is so much more left to discover in the book.

Notes

[1] Strathie, Anne, Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker, The History Press, 2021, p. 207. See the review of this book here.

[2] Bennett, Terry, “Photographers, Judo Masters & Journalists: Herbert George Ponting, 1870-1935”, in Japan Society’s Biographical Portraits, vol. IV, part 5, pp. 303-304.

[3] Talk by Anne Strathie for the Royal Photographic Society, Wednesday, 28 April 2021 on her book Herbert Ponting: Scott’s Antarctic Photographer and Pioneer Filmmaker.

[4] UK Parliament, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/electionsvoting/womenvote/overview/thevote/

[5] Hotta-Lister, Ayako and Nish, Ian (eds.), Commerce and Culture at the 1910 Japan-British Exhibition, Centenary Perspectives, Global Oriental, Leiden and Boston, 2013, p. 112.