To The Kwai – And Back: War Drawings 1939-1945

By Ronald Searle

Souvenir Press

2006, 192 pages

ISBN 0285637452

Review by Sean Curtin

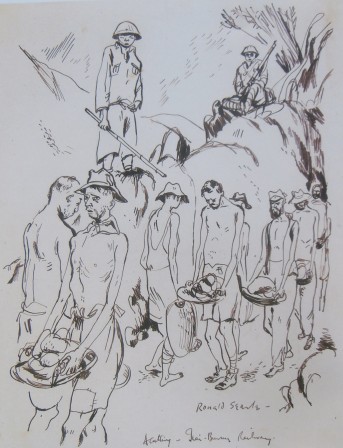

This disturbing book was previously reviewed back in Issue 3 (May 2006) by Sir Hugh Cortazzi but is worth examining again as it contains one of the best contemporary visual records of the terrible sufferings endured by the prisoners-of-war who built the Thai-Burma Railway(1). Written narratives are often unable to convey the full horror of the inhuman regime which Ronald Searle’s grim depictions so brutally portray(2).

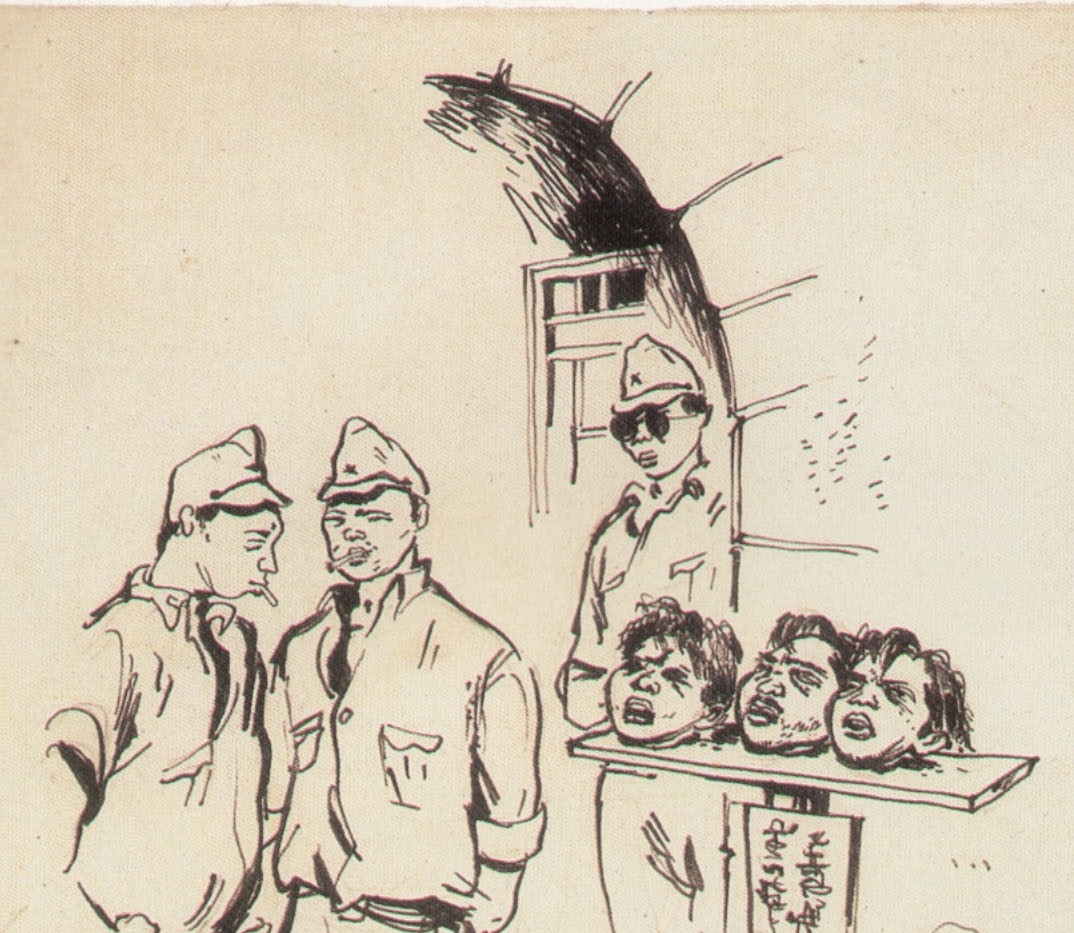

Searle (3 March 1920 – 30 December 2011) was a gifted artist who was captured by the Japanese in February 1942, remaining a PoW until August 1945. The book tells his story from the fall of Singapore to his survival against the odds and eventual liberation. The text is fairly limited allowing the many finely drawn sketches to tell their own gruesome tale. While Searle’s focus is on his and fellow captives’ suffering, I was also shocked by the extreme level of brutality Japanese troops inflicted on ordinary Chinese civilians. On page 66 Searle observes, ‘It is estimated that 20,000 Chinese alone were shot or beheaded during the first few days after capitulation [of Singapore].”

As one progresses through the book, the reader is confronted with an utterly dark world dominated by mindless cruelty and countless deaths. Life on the so called Death Railway was mercilessly harsh, the author notes, ‘…it was no holds barred and any prisoner not visibly about to drop dead was forced to work. Needless to say, this did not decrease the casualty rate, nor did it speed the advance of the railway (page 110).’ We are given a stark account of what the bleak daily regime was like and the tremendous loss of life it inflicted. Describing a typical day which would begin before dawn, Searle writes, ‘When we reached the bare rock just above the river, we were put to work, cutting into it with hammers and chisels until it was too dark to see any longer. Then we struggled back up to the camp that we rarely saw other than by the light of the bonfire. After two or three weeks, when the cutting was finished, we were moved further on up the track to hack out another (page 108).’

the Thai-Burma Railway

We are told of the regular sadistic torture Japanese troops remorselessly inflicted on the PoWs for their own amusement (pages 114-5). Searle fully understood the utter contempt with which he and his fellow captives were regarded, ‘we were not, it appeared, recognized as conventional prisoners-of-war as established by well-meaning but misguided politicians, but as shameful captives. The traditional Japanese military philosophy allowing no alternative to victory but death, we were dishonoured, the despised, the lowest of the low (page 80).’ While the physical treatment was intolerable, living conditions were equally unbearable, ‘It was not only the labour that nearly drove us out of our minds; it was also the insects, that curse of the jungle, and they ate us alive. Mosquitoes and foul fat flies were a horror, and their bites were often fatal. But it was probably the non-killers that made our lives the most miserable. At night after work, tired as we were, we were kept awake by swarms of bedbugs that wandered over us, sucking our blood and nauseating us with their smell when we crushed them. Day and night the lice burrowing under our skin kept us scratching. Sometimes giant centipedes wriggled into our hair when we finally got to sleep and stuck their million poisonous feet into our filthy scalps as we tried to brush them off, setting our heads ablaze (page 113).’ Searle depicts an absolute living hell and it is hardly surprising that many of those who survived this unimaginable nightmare were deeply traumatized and psychologically scarred.

When Sir Hugh Cortazzi originally reviewed this book for Japan Society Review Issue 3 in May 2006, he wrote, ‘I wish that Japanese historical revisionists and Japanese nationalists would read this book. They might then begin to understand why we object to Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi and Foreign Minister Taro Aso paying their respects at the Yasukuni shrine where the Yushukan museum glorifies war and the Japanese military. They should be remembering all those who died and suffered during the war including the civilian dead in Singapore and, of course, in Japan itself.’ Searle’s vivid sketches brilliantly capture the horror of daily life on the Thai-Burma Railway which he compares to the Dark Ages, but adds, ‘unlike the medieval warriors in the jidai-geki (period drama) of Kurosawa, there were no heroes. Merely killers and survivors (page 9).’

from before dawn until after dusk

Notes

1) Other PoW artists who recorded the horrors of the Thai-Burma Railway are John Mennie, Jack Bridger Chalker, Philip Meninsky and Ashley George Old. Ronald Searle is perhaps best remembered not as a war artist but as the creator of the fictional St Trinian’s School and for his collaboration with Geoffrey Willans on the Molesworth series. The majority of Searle’s original war work is on display in the permanent collection of the Imperial War Museum in London, along with the work of other PoW artists.

2) See Sir Hugh Cortazzi’s original review in Japan Society Review Issue 3 (May 2006)