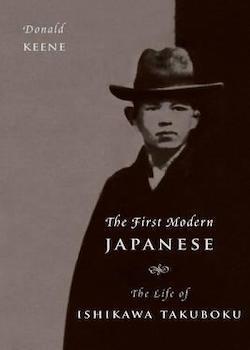

The First Modern Japanese: The Life of Ishikawa Takuboku

By Donald Keene

Columbia University Press, 2016

ISBN-13 9780231179720

Review by Sir Hugh Cortazzi

Donald Keene, Professor emeritus of Japanese literature at Columbia University and doyen of Japan studies in English, continues despite advancing years to produce well-researched, well-written, informative and interesting studies of Japanese personalities and historical themes.

Takuboku Ishikawa (1886-1912), the subject of this study, is little known outside Japan and according to Keene increasingly overlooked in Japan. For a time he was ‘Japan’s most popular poet. He still is popular but many Japanese have lost interest in works of literature unlikely to appear in university entrance examinations.’ This is a pity because, as Keene tells us, he ‘probably ranks as the most beloved poet of the tanka […] Takuboku’s tanka stand out less for their beauty than for their individuality; his poems are as surprising today as they were for the first readers’.

Like Masaoka Shiki (see Cortazzi’s review of Keene’s biography of Masaoka here) the poet who modernized haiku, Takuboku, who used the classical language (bungotai) in his tanka poems, eschewed the conventional themes such as the blossom falling or other images suggesting the passing seasons and took as his inspiration everyday modern objects such as trains.

Takuboku thought that the terseness of the tanka form was not an obstacle to expressions of emotion, as some other contemporaries did, but rather kept ‘the poet from exaggerating his emotions’. Nevertheless he could not remain immune to traditional Japanese themes such as the brevity of life. The Japanese word suna (sand) which he used in the first ten poems of his most famous collection of poems, A Handful of Sand, suggested ‘the passing of time, like sand in an hourglass’.

Takuboku wrote some poetry (shi) in other forms, as well as stories and literary criticism. His most famous prose work was his Romaji Diary. He claimed implausibly that he used roman script to keep its contents from his wife. The diary is an example of Japanese extreme introspection. It is revealing of his emotional life and his worries and aspirations. It is also an explicit account of his life including his sexual encounters. Despite his promiscuity ‘his love for his wife Setsuko remained unchanging and passionate’. She overlooked his infidelities and even forgave him for missing his own wedding. He arrived in Morioka five days after the ceremony had taken place without the bridegroom.

Takuboku was born in a tiny village in Iwate prefecture as the son of a Zen Buddhist priest. His mother who was devoted to him indulged him. He did well at school and read widely if unsystematically in English as well as in translation from Russian and German. He became fascinated with Wagner as a dramatic poet but showed little interest in Wagner’s music.

Russian literature ‘awakened him to the idea of downtrodden masses’ and encouraged his rebellious spirit. He was influenced by anarchist concepts and in May 1911 wrote a version of the ‘letter of vindication’ written by Kotoku Shūsui who was charged in a high profile trial of having plotted to kill the Meiji emperor.

Before finding work he had thought of moving to America but was refused a passport to travel abroad. So in 1906 he decided to return to Shibutani, his old village in Iwate, ‘where he could write without interference’. But he had to earn a living. So he became a schoolteacher.

He described his time in Shibutani ‘as a lonely year in a lonely village’. He was dissatisfied by the way the school was run and called on the principal to resign. The principal refused. So Takuboku resigned and decided to move to Hokkaido.

He went first to Hakodate where local poets found him a temporary job at the Hakodate Chamber of Commerce but this was unpaid. He got a temporary teaching job where he fell in love with one of the women teachers. He was also asked by the local newspaper to write a weekly poetry column, but after only two of his articles had been published there was a devastating earthquake and fire in Hakodate and the paper’s premises were destroyed.

Takuboku’s ‘exile’ to Hokkaido then took him to Sapporo, Otaru and eventually to Kushiro where he was employed by the local newspaper. In Kushiro he led a dissolute life of drinking and womanizing. This life style exacerbated the tuberculosis, from which he was already suffering and which eventually killed him. He decided to escape from what was then a remote and desolate part of Hokkaido and scraping together the fare he left by sea for Yokohama.

He went on to Tokyo where he was able to mix with other writers such as Mori Ōgai and pursue his literary interests. Unfortunately the stories, which he had hoped would enable him to make a living, failed and his poverty exacerbated his depression and misanthropy. He was eventually employed by the Asahi although only as a proof reader. In 1909 his wife rejoined him. But Takuboku was constantly in debt and deeply depressed. In Garasu mado (Glass Windows) he expressed his ‘derision for all varieties of literature’. He was however beginning to be recognized more widely as a writer and poet.

Takuboku’s health continued to decline. He quarreled with Setsuko telling her that they were divorced but Setsuko who was also suffering from tuberculosis as was his mother continued to live with him. In 1912 first his mother, then Takuboku and two months later Setsuko succumbed to thr disease, which was a rampant killer in Meiji Japan.

Professor Keene has drawn a sympathetic portrait of an important figure in Japanese literary history. His book also contains interesting descriptions of life in late Meiji Japan.