Node

Directed by Koike Atsushi

2010

Review by Roger Macy

In early 2017, the Japan Society in London put on three evenings of screenings of films with the Royal Anthropological Institute, curated there by George Barker. Sandwiched between the screenings of Kim Longinotto’s Gaea Girls and two documentaries related to the Ainu people in Japan was Koike Atsushi’s Node, a careful, Japanese-made study of a community, which has had no other screening outside of the University of Tromsø, for whom it was made.

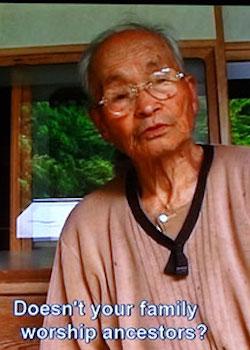

Node – there is only an English title, relies entirely on the Japanese dialogue of its subjects. The English subtitles provided were more than an aid, as much better speakers than I were unable to grasp all of the dialect. It’s a study of the residents of a depopulated village, Hirogawara, in forested hills northwest of Kyoto.

The film starts as it means to go on. After a brief landscape shot, the camera is waiting patiently in an old woman’s kitchen. She will speak when she’s ready, after she has got us our cup of tea, and begins to tell us how her 70 years of service at the temple started, on the say-so of her brother-in-law. There is no sense of the filmmaker pressing questions; but he isn’t entirely inaudible – sometimes the unseen Koike will answer interviewees’ questions and let them continue.

That style of patient sympathy with the subject soon told me that Koike was immersed in styles and theories of Japanese documentary-making that foreground the relationship with the shutai – the subject. They are exemplified in the work of Sato Makoto and Ogawa Pro. As it transpired in the recorded interview with the director shown immediately after the screening (1), this was the origin of the title ‘node’, in its geometrical sense of an intersection,. Koike is objectifying the intersection of the subject and filmmaker.

But there are other nodes. It becomes apparent by the second scene that, as in traditional Japanese villages generally, there are frequent intersections between the living and the dead. And in this current era, there are intersections between the chronically depleted population of the village and those whose livelihood has taken them away from the village but still have connections to it.

On returning from a shrine, one neighbour reports to another on an extended burglary of a home that had gone unnoticed.

The reasons hereabouts for depopulation are connected to forestry – the initial impetus for Koike’s investigation of the village. Forest monocultures project their one moment of harvesting into the future, with little in the way of interim labours or reward. A couple report that the price for their 20,000 trees isn’t worth the felling. That speaks of our global value placed on environmental resource. With no history of monetary income, old people there have missed on pension entitlement.

Koike’s reticence was taken to its most patient extreme in the takes with a single old man who recounts his war experience, interspersed with remarks about the dos and don’ts of fishing. He recounts that killing the enemy used to seem normal, that he even boasted of it. Without a break, those running away from him have become ‘farmers’. They leave a baby in their house, which he feeds. A long pause is uncut and we’re back to fishing. I couldn’t have resisted asking more.

A 100-day death commemoration contrasts strongly with the interviews. The returned emigrants speak in a more recognisable Japanese, formal for the occasion. The son of the deceased, the new family head, welcomes and thanks the guests. A ceremony is chanted; to which family members rotate a circular rope from hand. I suppose each family member, resident or non-resident, is a node on this circle. With no cuts in the filming, we see a small boy evolve from amused fascination, to sleepiness, and to sleep itself, at which point he is silently carried away to the next room by the new, and modern, family head.

We simply close with a few more fishing tips. But between each scene are punctuation shots. Some depict local scenery but many depict an equally patient toad, who finally catches his meal.

The film to me seemed eminently a calling-card for Yamagata, the biennial documentary film festival that arose out of the original Ogawa Pro. But it was never accepted there. So it remains in the memory purely of the Japan Society and callers by appointment at the Royal Anthropological Institute.

(1) With thanks to Akiho Horton, who recorded an interview with Koike-san in Japan that was shown after the screening.